While Texas gets a reputation among national developers as one of the easiest places in the country to build, Austin has long had some of the state’s strictest zoning regulations. But the state’s capital city, in the grips of a housing crisis, is changing its tack.

In late July, the Austin City Council passed a resolution to decrease the minimum single-family lot size from 5,750 square feet to 2,500 square feet. The plan, introduced by Council member Leslie Pool, would also amend the development code to allow at least three housing units per lot (the current maximum is two).

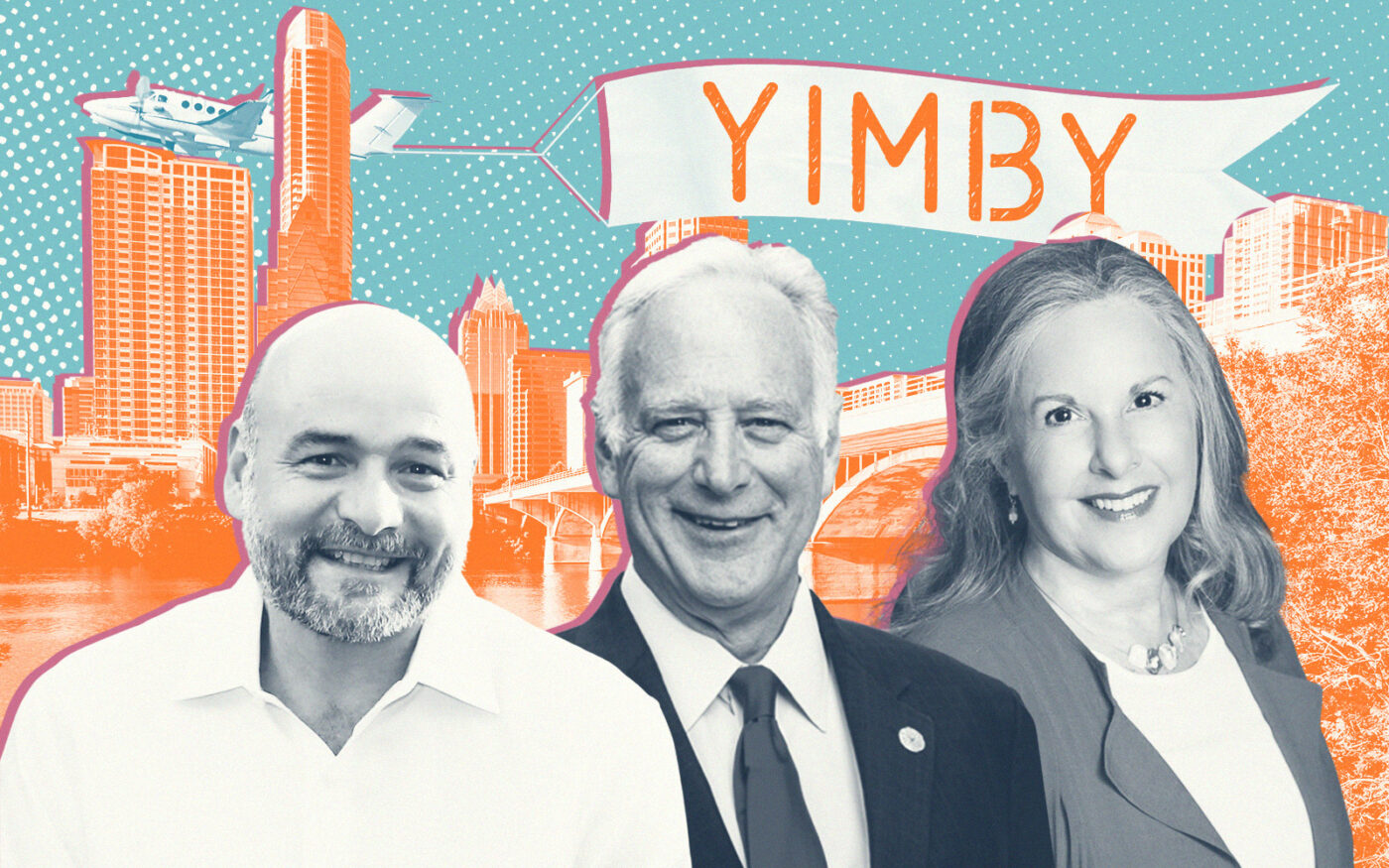

In other words, Austin could soon see a spurt of triplexes, townhomes and other small multifamily developments in single-family zoned districts. The resolution is one of a series of recent wins for the city’s so-called “YIMBYs,” a loose coalition of residents who advocate for more density in development, major increases to the housing stock and a move away from the sprawl that has so far defined the Texan approach to growth.

Not everyone is thrilled by the move — one resident at the council meetings called it a “let them eat cake policy,” and resolution sponsor Leslie Pool pushed back against doomsday interpretations of the plan.

“It does not eliminate single-family zoning districts. It does not change the zoning on anyone’s property. It does not force a reduction of existing single-family lots,” Pool told the Austin American-Statesman. “It does not make any changes today.”

But the text of her resolution makes clear that Pool and her colleagues are taking seriously the notion that the way out of Austin’s housing crisis may be built by developers. In less than a year, the council and Mayor Kirk Watson have pieced together at least three major reforms to Austin’s land development code to spur more housing, in addition to smaller initiatives to grease the wheels. Together, the reforms mark a major step in the city’s zoning evolution. After years of muddling about as home prices and rents shot up, Austin’s politicians appear to have decided on a course of action.

After taking office in January, Watson hired consulting juggernaut McKinsey & Company to analyze what he calls the city’s “wildly inefficient” development review process. Discussing the unreleased study at a recent event held by the Austin Board of Realtors, Watson laid out his city’s process in disbelief.

There are 1,470 steps in the formal review process, so it would take 20 full-time employees a full week to complete a formal review cycle, McKinsey found. And the average application goes through five review cycles.

“Calling that process ‘inefficient’ is a gross understatement, from a man who’s not known to be understated,” Watson said.

Watson even spoke in the economics-inflected language of the YIMBY, noting that the city’s restrictive zoning “drives up costs” and “limits the supply.”

During his mayoral campaign, Watson drew a contrast with his opponent’s call for comprehensive zoning reform. He said he would approach zoning reform neighborhood-by-neighborhood. That piecemeal process is now taking shape in the council.

In May, the Council passed a resolution to eliminate citywide parking mandates, and in June, it moved to reduce the city’s “compatibility” standards which limit building heights depending on how close they are to single-family homes. Those standards are meant to prevent huge buildings from cropping up next to houses, but in Austin, they stretch much further than those of other cities.

Right now, Austin has at least five compatibility standards spread across dozens of pages of code. Many cities don’t have compatibility standards, and even those that do rarely extend them further than 100 feet from single-family homes. In Austin, the restrictions can force setbacks and height restrictions on buildings as far as 540 feet from a single-family home. The council now wants to cut the restriction to 100 feet or less.

“When I speak to both nonprofit and market-rate developers, everybody identifies Austin’s compatibility rules as our number one barrier to housing,” Council Member José Vela said in a meeting discussing the proposal.

“Austin’s policy makers were taking an all-or-nothing approach to land use changes,” Watson said at the Austin Board of Realtors event. “We’re making progress on housing now because we all understand that doing nothing is not an option.”

Read more

The minimum lot size resolution reads like a page out of a YIMBY’s dream journal. It cites data on rising housing and land costs. It notes that in 2020, after a decade of 20 percent population growth, smaller-scale homes like townhouses and triplexes made up just 12 percent of Austin’s housing stock.

It also cites Stetson University law professor Paul Boudreaux, whose paper “Lotting Large” makes the case that large minimum lots block affordable housing. “By restraining the supply of housing, large lot zoning laws please existing suburban homeowners. But they harm all other segments of the American populace, including the million new households who seek a home in the United States each year,” Boudreaux writes.

The paper has been cited in more than two-dozen other studies, many of them arguing for cutbacks to local zoning codes to spur more development, a core YIMBY tenet. One, titled “Do Minimum-Lot-Size Regulations Limit Housing Supply in Texas?” concludes that even modest minimum lot sizes lead to less dense cities than people want.

Opponents of YIMBYs have often maligned them as ivory tower eggheads, but here, council member Pool is translating the research into policy.

Felicity Maxwell, an Austin planning commissioner and a board member of the Austin urbanist organization AURA, supports the council’s moves toward promoting housing development and hopes future reforms help encourage development along new Project Connect stations.

“At some point you have to talk about what are we building around these train stations and fancy bus stops,” Maxwell said.

City staff will have to translate the council’s resolutions into legally sound amendments to the city’s land development code, a legal document. That may take time, and even if passed, Austin will still have stricter land development regulations than other Texas cities. Many Austin neighborhoods that are well positioned for multifamily development aren’t zoned for it. And in Houston, for example, the minimum lot size is just 1,500 square feet. Dallas Council member Chad West recently called on his city to match Houston’s minimum lot size.

Austin’s resolutions have yet to become law, and will surely face pushback. But the city’s urbanists now have a critical asset on their side: momentum.

“We’ve seen a fundamental shift in this city. People who are pro-housing, urbanists, YIMBYs,” Maxwell said. “Whatever you want to call them, we’re here.”