The eminent domain brawl between Todd Interests and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission has been a monthslong war of words. But now Todd has receipts.

Todd Interests founder Shawn Todd revealed the first batch of emails and texts he received from a series of open records requests to the commission. The messages were meant to shine a light on what he describes as a state plot to seize his 5,000 acre development site just south of Dallas and hurt his firm’s reputation.

“This type of behavior and deception should scare the hell out of every rancher, farmer and property owner,” Todd said in an interview. “This is bigger than this real estate deal. This is wrong.”

The state has denied wrongdoing and said Todd’s timeline for an acquisition was not reasonable.

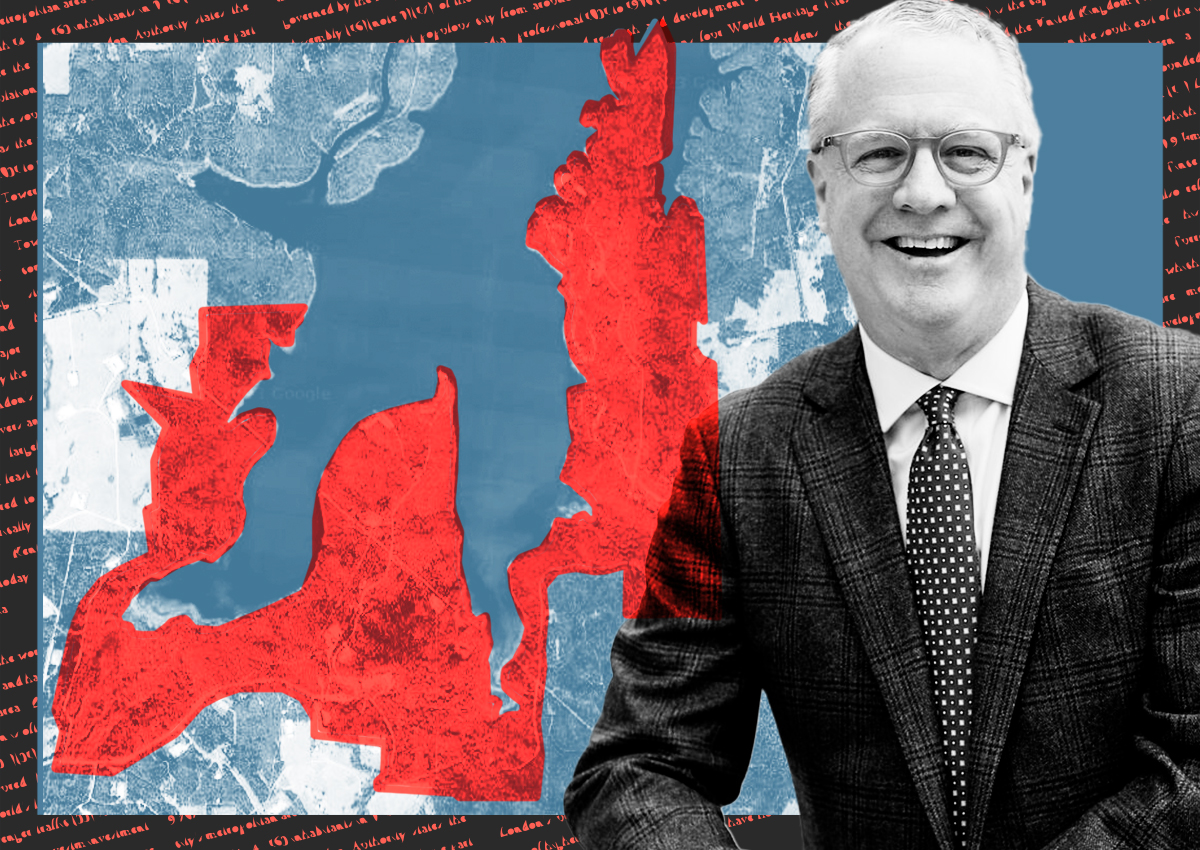

The saga centers on Fairfield Lake State Park, an 1,800-acre park that the state has leased from Vistra Energy for about 50 years. In June, Todd closed on a development site that includes the park plus 3,200 acres of surrounding land and a 50,000-acre reservoir. The developer plans to build a $1 billion resort with 400 homes and a golf course on the property. Meanwhile, the state has been under pressure to save the park and weighing whether to force Todd to sell it the land through eminent domain.

Todd and former Parks commissioner Arch “Beaver” Aplin III, the Buc-ee’s CEO who launched the eminent domain effort, have been at odds for months. Here’s what the new records show:

Blood in the water

One of the most valuable pieces of Todd’s development site is the large reservoir in the center of the land. While the value of the water is unclear, Todd said his lender appraised the reservoir and its water rights at $238 million, more than double the $103 million he paid for the site.

Back in February, before Todd closed on the property, Aplin texted the commission’s former director Carter Smith and his replacement, David Yoksowitz, about how the water rights could help the state afford a deal. He appears to be aware that the water rights were valuable and willing to use that value to drive down cost.

“Carter, want to talk about feeling out some water people to see if they would like a water deal with us if we owned the water rights to lower our cost,” Aplin wrote.

But when Todd closed on the property in June, the commission released a statement saying the developer may monetize the water rights and damage the lake. In particular, the statement says the commission had “reason to believe” Todd planned to divert water from the reservoir, drawing its volume down by a third and threatening wildlife.

“Todd Interests has chosen to raze a public asset that is beloved by Texans and welcomes more than 80,000 visitors each year,” Aplin said in the release.

On June 2, the state announced it was considering eminent domain.

The counter-offer

The records also shed light on just how close the state and Todd came to striking a deal to keep the park in state hands.

In May, the state offered Todd $25 million for its contract with Vistra. That was $15 million short of the $40 million price Todd had set, but as the closing neared, the developer gave the state a final counter offer: if they said yes by 1 p.m. the following day, the contract could be theirs for $30 million.

At the same time, Aplin was negotiating with Vistra CEO Jim Burke to drive down the purchase price of the land. Burke texted Aplin that he was seeking board approval to sell the park for $95 million, down from the $103 million Todd was set to pay.

That would set the state’s final acquisition cost at $125 million, the exact amount the Legislature gave the commission in early June to buy land in the next two years. Todd said he never heard back from Aplin and that the commissioner never mentioned the offer to anyone else, charges the commission disputes.

“Chairman Aplin tried to contact Shawn Todd three times on May 24 — calling and sending two text messages — and worked with Shawn Todd through Jim Burke, the CEO of Vistra, May 25 to finalize an agreement with Todd Interests,” a spokesperson for the commission said.

Further complicating the deal, the Freestone County Commission was not set to vote on the acquisition until May 25, and the parks commission’s lawyer said the offer could not be accepted until it was heard and voted on.

Todd responded on May 24 that he wanted Aplin and the board’s commitment, notwithstanding a formal county commission vote.

On June 2, the day after Todd closed on the land, parks explained that the parties couldn’t reach a deal.

“TPWD extended a formal offer to Todd Interests and, with the full support of our commission, we were vocal in our intention to conduct realistic negotiations with realistic conditions,” wrote David Yoskowitz, executive director of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “Unfortunately, Todd Interests would not work with us, and we now need to pursue other options.”

A spokesperson for the parks commission said Todd wanted an answer before the state could lock down the funding it would need. The House did not pass the appropriations bill until May 27, four days after Todd sent his offer. Gov. Greg Abbott signed it into law on June 9, more than a week after Todd’s closing date.

“Shawn Todd wanted payment within a few days, after being informed that payment would not be available until late summer due to timing of appropriations,” the spokesperson said. “Todd demanded an answer within 24 hours, ahead of the TPW Commission meeting.”

“Exceptional and unusual circumstances”

The Parks commission has repeatedly said it does not plan to abuse eminent domain to take more land from Texans, and that it considers Fairfield Lake State Park to be a unique situation.

“This rare activation of eminent domain authority is a last resort to save an existing state park that Texans have enjoyed for the past 50 years,” Aplin wrote in an op-ed explaining his position. Jeff Hildebrand, who replaced Aplin as Parks commissioner in August, has noted that the commission has not used its eminent domain power in nearly 40 years.

The commission even voted to limit future uses of eminent domain to “exceptional and unusual circumstances” during the Fairfield Lake fight.

In February, then-Chairman Aplin testified to a House committee that his agency was not committed to using eminent domain.

“This agency doesn’t have a view about eminent domain. If this legislature creates eminent domain on this lake, then I will follow my orders and do what’s told by the legislature, but not this agency,” Aplin said. That statement does not explicitly rule out using eminent domain absent state intervention, but two bills authorizing the state to use eminent domain to save the park failed in the legislative session.

Todd argued at the press conference that the money the parks commission received for land acquisitions has to go to “willing sellers,” citing the commission’s request for appropriations from 2022. Parks counters that the final wording of the bill never uses the phrase.

In January, Aplin texted Doug Deason, a Dallas businessman and conservative donor who led a push to create a $1 billion fund to build and buy new state parks.

“Did you know we’re possibly losing Fairfield State Park?” Aplin wrote.

“Yes! The $100 million already in the budget and this bill should give you the resources to save it,” Deason responded. “I think the state should use eminent domain to punish those bastards!”

Read more

Todd Interests says it has worked with two law firms to file public information requests. So far, the state has released a small fraction of what Todd requested, the developer said. His firm plans to file a lawsuit forcing the state to release the rest.

Aplin and Deason did not return requests for comment by press time.

If approved, the requests would give Todd access to more emails, texts and phone records of key Parks department leaders and politicians.