An unknown buyer has snapped up the $725 million in debt on two of San Francisco’s largest hotels, according to servicer commentary.

Virginia-based Park Hotels walked away from the 1,921-room Hilton San Francisco Union Square and 1,024-room Parc 55 San Francisco in 2023 and Eastdil began marketing the debt for sale last July.

“Offers have been reviewed and a buyer has been selected,” specials servicer Trimont Real Estate Advisors told commercial mortgage-backed security bondholders. “A non-binding term sheet has been executed and draft purchase and sale agreement is being negotiated.”

The note cautioned that material terms were under discussion by the receiver and the buyer, so there is still a risk that the sale will fall through.

The properties, which are the city’s first- and fourth-largest hotels, respectively, were worth a combined $1.56 billion when the loan originated in 2016. But that value had dropped by $1 billion by last summer amid severe declines in post-pandemic revenue and occupancy. Performance at the two properties continues to dip, according to the Trimont comments. At the end of 2024, they had a combined 40.5 percent occupancy, and just $96.24 revenue per available room, or RevPar.

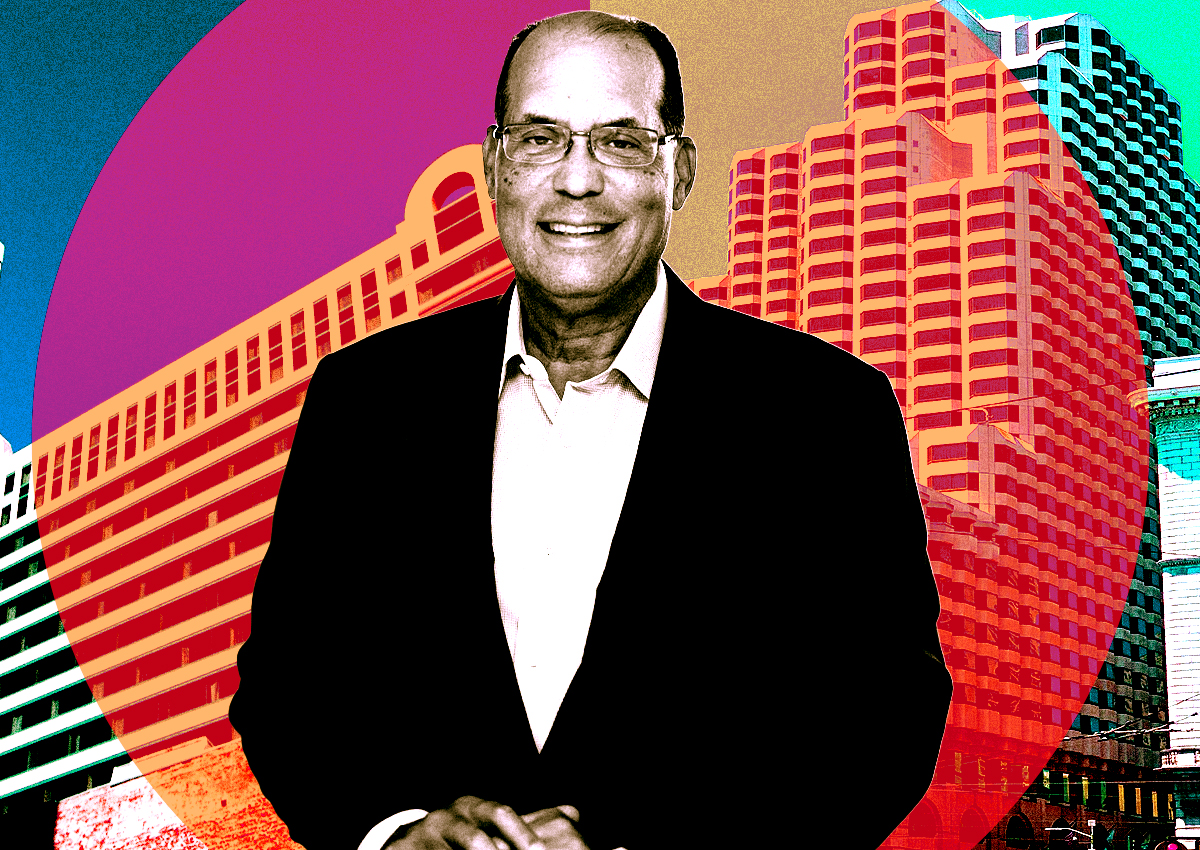

When the loan originated, the two hotels were 90 percent full and their average RevPar was $217, according to Alan Reay, president of Atlas Hospitality Group, a Newport Beach-based brokerage that focuses exclusively on California hotel sales.

“That’s 200 percent more than it is today,” Reay said. “There’s no question why hotels like these two, as well as other major full-service hotels in San Francisco, are really struggling and having a big problem with debt.”

Eastdil did not immediately reply to a request for comment on the deal, which would need to close by March 31 in order to avoid going back to lender JP Morgan Chase for foreclosure. Reay said that the deal would ideally close by then, but the courts would likely allow an extension of the receivership if it is still in the works at the time.

Setting the new market

The eventual sales price of the debt on two hotels that make up 20 percent of San Francisco’s entire hotel stock will be a major transaction with wide implications for hotel debt around the Bay Area, Reay said.

“It’s going to set the new market in terms of price per room,” he said, impacting not just appraisals of hotels on the market, but those who have loans coming due and need refinancing.

The “knock on” impact is likely to be limited to the Bay Area, which also makes up the majority of the $6 billion in California CMBS hotel debt at a high risk of default, Reay said.

“We have, for want of a better term, a ticking time bomb,” he said, mainly brought on by how far the area’s hospitality fundamentals have fallen since the pre-pandemic heights. “With tech, office, meetings and conventions, you were operating at 90 percent occupancy. When all that disappeared, those are the markets that have been hit the hardest.”

These factors are a particular problem for the two Park Hotels-owned properties in San Francisco, as both depended on the city’s office sector, according to Chris Meyer, an analyst at Morningstar.

“We’re several years away from what would be deemed a healthy office market,” Meyer said, adding that Park Hotels likely didn’t want to wait out a lengthy turnaround, “funding two properties in financial distress” in the interim.

The sale could reflect “the general health of the city’s central business district,” Morningstar’s Sarah Helwig said.

“I would say the hotels offer less of an apples-to-apples comparison when looking at hotels outside San Francisco,” the vice president said. “Similarly, hotels that are outside of the downtown and don’t rely on business travel are also in a different bucket.”

The Hilton Union Square in particular was “highly dependent” on conventions at the Moscone Center, Meyer said, which could take another five years to recover.

Trimont comments said group room nights, or room blocks, at the two hotels had fallen from 619,000 in 2023 to a predicted 414,000 for group rooms in 2024, but in fact fared far worse than that expected number. There were fewer than 70,000 group rooms booked in the first three quarters of 2024, according to Trimont, with a major slowdown in the second half of the year.

According to Reay’s data, the hotels operated at a deficit of just under $23 million a year in 2024, not including an additional $30 million in debt service obligations. He said he has heard estimates that it could take 10 years or more for Moscone to recover, meaning the buyer is likely looking at a “very, very long-term horizon.”

“Let’s just say you gave me these hotels for free. I’m still operating at a $23 million-per-year negative so I could be looking at $250 million [in losses] over the next 10 years if I still operate them like they’re operating,” he said, adding, “This is not an operator problem. It’s a market problem.”

His guess was that the unknown buyer could be planning at least a partial conversion to residential, although there is a big question of whether the city would allow that conversion since Mayor Daniel Lurie just helped negotiate a new union contract for hotel workers after months of strikes. But the city also has state-mandated requirements to create more housing, especially affordable housing, and it costs substantially less to convert a hotel than an office building.

The buyer will also probably need the ability to buy the debt all-cash because the receiver would be unlikely to approve a sale with a loan contingency, Reay said. Those who have been buying distressed offices in the city might also fit the buyer profile for the hotel deal, and could partner with a local hospitality operator, if it seems like a good enough opportunity.

“The buyer is going to have to get themselves a good deal to make it attractive,” he said.

But what a good deal means in this case could vary widely depending on what the buyer is allowed to do with the property, he said. It will certainly trade at well below replacement costs, which Reay estimated at $2 billion to $3 billion. Plus, he added, there’s no new hotel supply coming to the market for a “very, very long time,” so a hold-minded buyer could be seeing a very positive return on their investment within the decade.

“If you could buy it at a good enough basis, and you’re paying all cash, and you can reduce those expenses, and you stick around for the next five or 10 years, this could be back to $1.5 [billion] or $2 billion,” he said.

Read more