It’s been well over 30 years since the public review process for New York City development has been updated.

While much has happened since 1989, notably a worsening housing crisis, the approval process is exactly the same as it was in the days of Mayor David Dinkins.

Now, finally, Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or Ulurp, can be improved — and likely will be. The result would be more housing.

The mayor has convened a 13-member commission to propose City Charter reforms, which would take effect if approved by voters in November. The City Council has no power to water down the reforms, as it just did with the City of Yes housing plan.

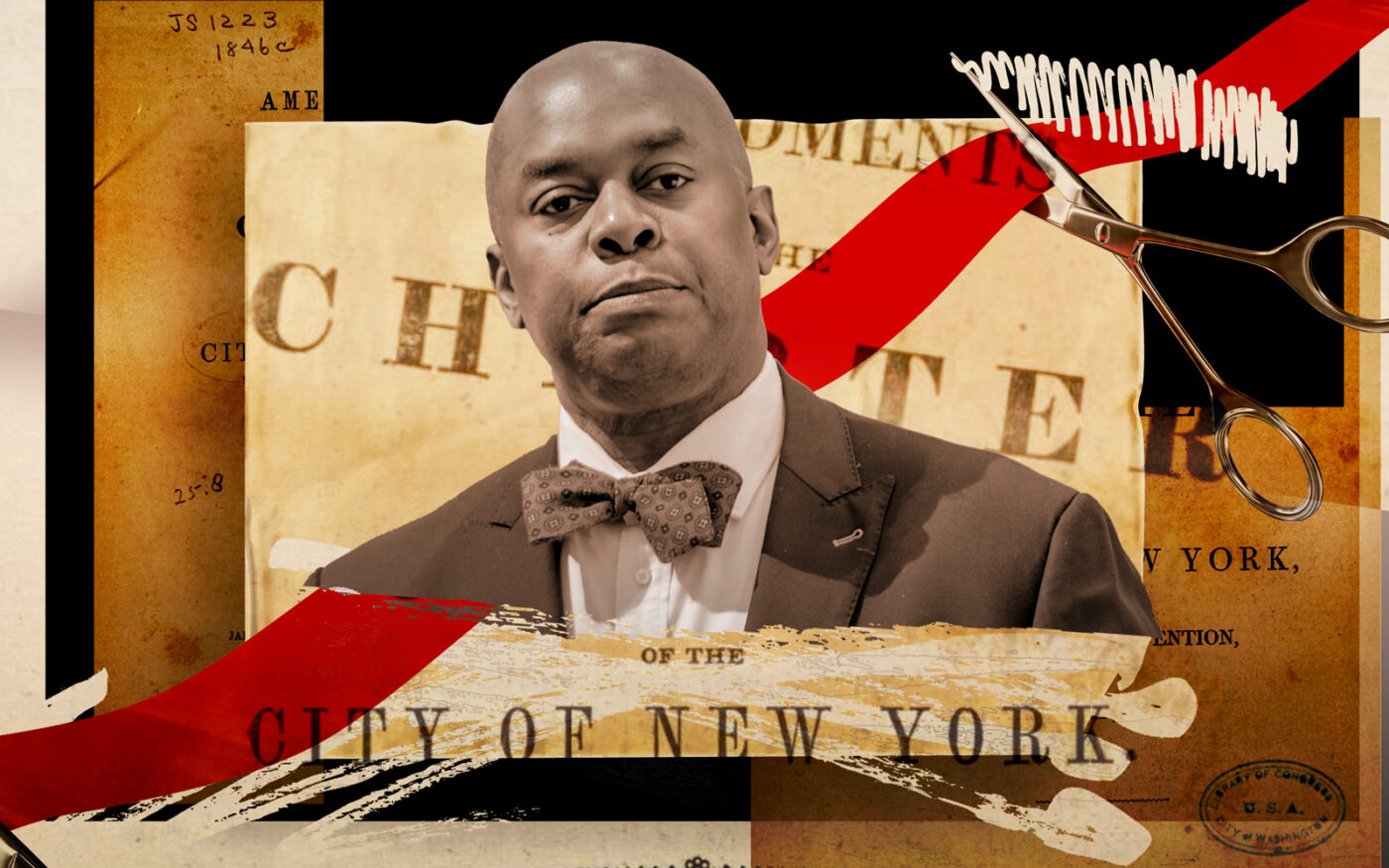

“There is broad agreement that it takes too long and is too complicated and expensive to do projects here,” Richard Buery, the commission’s chair, said in an interview.

But what will it put on the ballot?

“Ulurp has many strengths, including firm deadlines, transparency, and a level of public participation and open debate that far exceed the ordinary legislative process,” said Howard Slatkin, executive director of the Citizens Housing and Planning Council. “But it also contains built-in political incentives skewed against housing.”

One analysis found that it adds up to $82,000 per unit to project costs. It also creates risk, noted Vicki Been of NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate. That prevents countless projects from being proposed at all.

Here is my take on the key recommendations to amend it:

De-localize power. City zoning is often low-scale and outdated, so rezoning is crucial to adding enough homes to ease the shortage. But because of the Council’s custom of “member deference,” Ulurp lets a single member stop or shrink a project.

Slatkin testified that charter revision should shift power to a body that acts in the interest of the whole city, and away from the interest of NIMBYs. He calls the concept “local voice, citywide responsibility.”

Buery gets that. The CEO of anti-poverty nonprofit Robin Hood and former deputy mayor said his panel would look to “balance the importance of community boards…with a citywide approach to planning.”

Introduce builder’s remedy. This workaround allows developers an as-of-right alternative if a stubborn locality makes housing targets impossible to meet. California and other states have various forms of builder’s remedy.

Open New York is pitching a version like Chicago’s, but only for deeply affordable projects in high-opportunity areas that have added little housing. “Council members representing these low-growth neighborhoods would no longer have the ability to block new housing proposals that advance fair housing,” the organization wrote.

However, creating low-income housing in expensive neighborhoods would be difficult even with builder’s remedy, because the land is expensive and city-owned development sites are scarce.

The city needs a more expansive alternative than Open New York is floating — one that also applies to mixed-income housing and all neighborhoods.

Allow appeals. The Citizens Budget Commission would give final say on rezonings to a 14-member panel consisting of the City Council speaker and the City Planning Commission, which would have a citywide rather than myopic perspective.

A side benefit: Developers would no longer withdraw applications for fear of rejection by the Council. Instead, the 51 Council members would have to vote and be accountable.

Shorten the runway. Public review takes six or seven months, but projects need years to reach the starting line. The Furman Center’s Been says the best-case scenario for “pre-certification” is two and a half years, but large developments take four to six years and sometimes more. Carrying costs can be immense.

This can be shortened, she told the commission, by changing the decision-making process. “The longer the timeline, the greater the risk that the project won’t be viable once the project is certified,” Been said.

Speed up public review. Charter reform can easily trim the seven-month public review.

Community boards and borough presidents should not get a combined 90 days to issue an advisory opinion, according to the Citizens Budget Commission, which recommends merging their reviews into one 60-day period.

Why not make it 45 days? Or 30?

Community boards don’t need an exclusive review window. Let them submit opinions at any point, rather than before the borough president. Board members are volunteers, not experts, and would benefit from first reading the borough president’s review, which is written by land-use professionals.

Spare minor actions from Ulurp. Lots of modest, non-controversial applications must go through the same process as major ones. These should be decided by city agencies or commissions, the Citizens Budget Commission says, and one hearing should suffice.

Fast-track affordable projects. Several groups including the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development have proposed this idea. It would reduce costs, and also help builders circumvent rejection by affluent communities that assume low-income housing brings crime and chaos.

Low-income children raised in high-income neighborhoods tend to do well — probably because having high-achieving classmates opens doors and raises their aspirations.

ANHD’s Barika Williams recommended expediting proposals that advance fair-housing goals, but would deny that advantage in non-wealthy areas to projects with any market-rate housing.

That reflects an enduring fear of gentrification, and perhaps also affordable housing developers’ dislike of competition for sites. But concentrating poverty in entire neighborhoods has not worked, nor has refusal to rezone kept high earners from moving into communities of color.

Given these social dynamics, and the housing shortage’s effect on prices, the Charter Revision Commission should be flexible in embracing new housing. Indeed, new housing is the very reason for its existence.

“Smart people take advantage of a crisis,” Buery said, “and we have that opportunity.”

Testimony for the Charter Revision Commission may be submitted here.

Read more