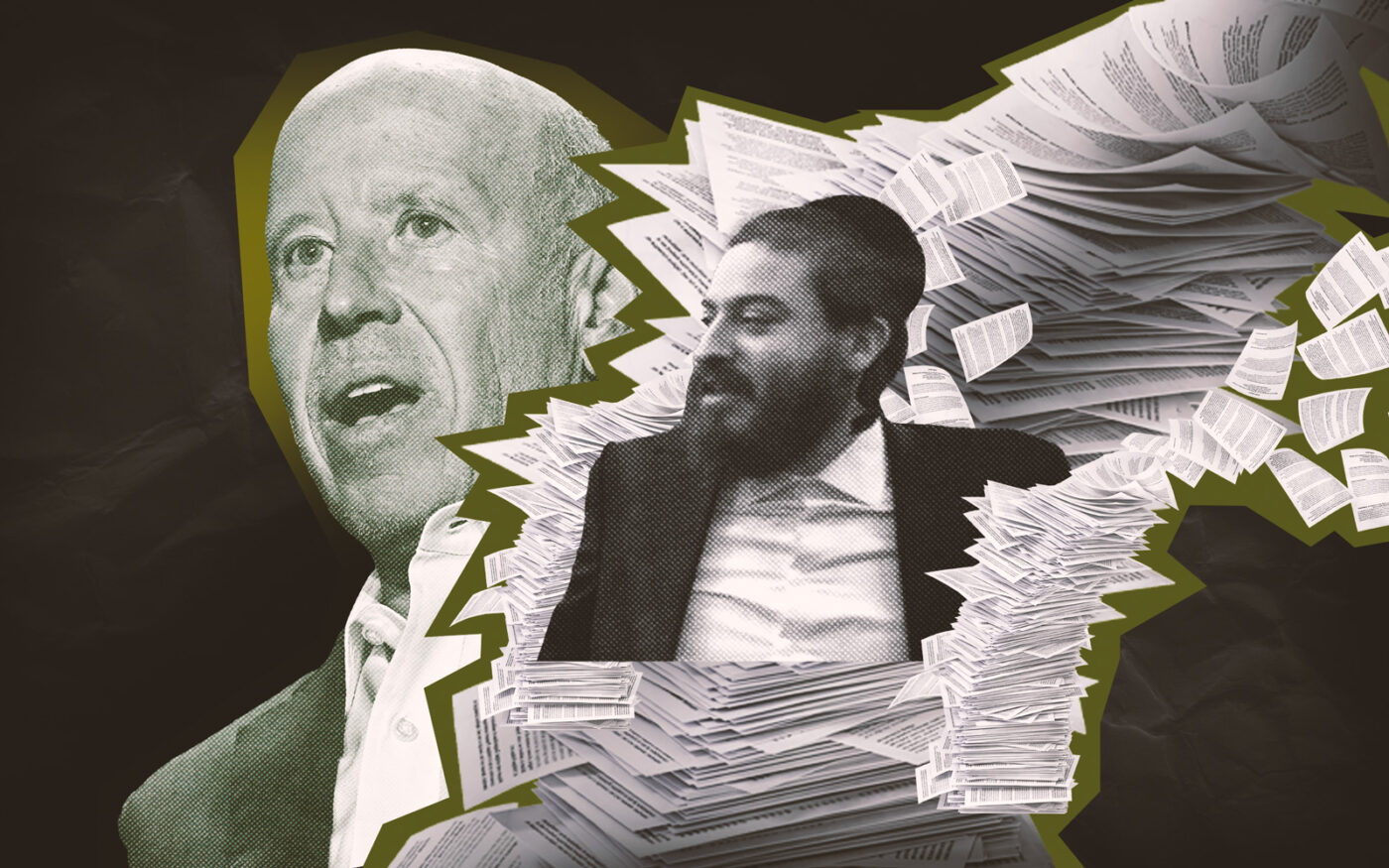

Joel Schreiber was reading his prayer book in a Brooklyn court room. For someone facing the possibility of prison, he seemed unfazed.

Schreiber was there because Starwood Capital has been trying to collect on two judgments against him that total over $88 million. The Jan. 13 court appearance followed a judge’s November promise that if Schreiber failed to hand over documents and respond to subpoenas related to one of those judgments, he could spend time in prison.

Perhaps in answer to his prayers, prison remained only a possibility for Schreiber by the end of the tedious three-hour hearing. The same judge, Kings County’s Aaron Maslow, wrote in an interim order that Schreiber has made “substantial efforts” to provide information and comply with the court order.

However, Schreiber, known for his early WeWork investment, still needs to respond in the format Starwood requested and provide all information his former lender wants.

Maslow ordered another hearing in March. “They are going to get everything they are entitled to if it exists,” Maslow said, referring to Starwood.

The judgments relate to loans Starwood provided for Schreiber’s Broadway Trade Center in Downtown Los Angeles. In 2018, Schreiber and Jack Jangana signed personal guarantees on a $213 million loan from Starwood for the L.A. property at 801 South Broadway. A year later, the debt was upped to $219 million.

Another day in court

Schreiber showed up to court in a blue suit with his peyos tucked behind his ears. He spoke in a soft voice with an occasional lisp, arguing he had done his best to adhere to the court order. Schreiber’s attorney Kevin Nash sent more than 18,000 pages of documents to Starwood’s counsel two weeks before.

The judge dissected Schreiber’s compliance with the court order’s grueling process, item by item, for much of the hearing, including the format of Schreiber’s responses.

One moment of excitement occurred when two young Lubavitchers showed up at the back of the courtroom behind Schreiber.

The duo, one tall and the other short, happened to have a hearing the same day over the illegal tunnels dug beneath 770 Eastern Parkway. As Schreiber’s hearing went on, the smaller of the two occasionally eyed the one reporter present in the otherwise empty room.

Another came when Starwood’s attorney David McTaggart of Duane Morris argued Schreiber had still not fully complied with a previous order because he did not send written responses to an information subpoena. He claimed Schreiber was moving money across different bank accounts. Schreiber’s attorney denied this allegation.

“There is no proof of that,” Nash said. “I wish we had money to move.”

At one point, Nash complained about the negative impact of press coverage of Schreiber.

“What press?” said Maslow.

“The Real Deal,” Nash responded.

Maslow reminded Nash about the existence of the First Amendment.

(Reached for comment later, Nash requested that TRD “provide a fair portrayal of events, and [show that] the court required that we reorder and reorganize the answers while opening with the recognition of Joel’s substantial efforts.”)

At the hearing, Nash told the judge that his team had so doggedly been assembling the needed documents that “they will hate me when I get back to the office.”

He also claimed Schreiber did not have the funds to pay the judgment and said Schreiber is trying to fend off a personal bankruptcy.

Schreiber’s early investment in WeWork had tremendous value at the time, and he later put money into a different co-working company, but was wiped out. He started facing judgments from creditors, according to Nash. (That includes a $22 million judgment from Goldman Sachs).

“He is trying to rebuild his life as best he can,” said Nash. “But it’s been a struggle.”

For years, the mercurial Schreiber has said he’s either broke or having liquidity issues. In a March 2018 deposition, which was part of a lawsuit in bankruptcy court, Schreiber claimed to have liquidity problems because some of his properties were not producing income.

But the mystery is what happened to the money he made on his WeWork stock. Schreiber cashed out on at least $44.6 million of it in August 2017, according to Reeves Wiedman’s book “Billion Dollar Loser.” Schreiber also continued obtaining loans and buying real estate, including Broadway Trade Center and Union Bank Plaza.

When Starwood recently deposed Schreiber, he responded “I don’t recall” or “I don’t know” 600 times in response to a Starwood attorney’s questions.

Another complication for Starwood’s attempted collection is that Schreiber has not yet filed his 2023 tax return. “I’m a citizen of the United States, and I can decide when to file and when not to file, and that’s my decision,” he said.

As the January hearing waned, Nash seemed to check the clock. He had to leave the court room to get on Zoom hearing for another client, leaving Schreiber momentarily alone as the judge wrote his decision.

Read more