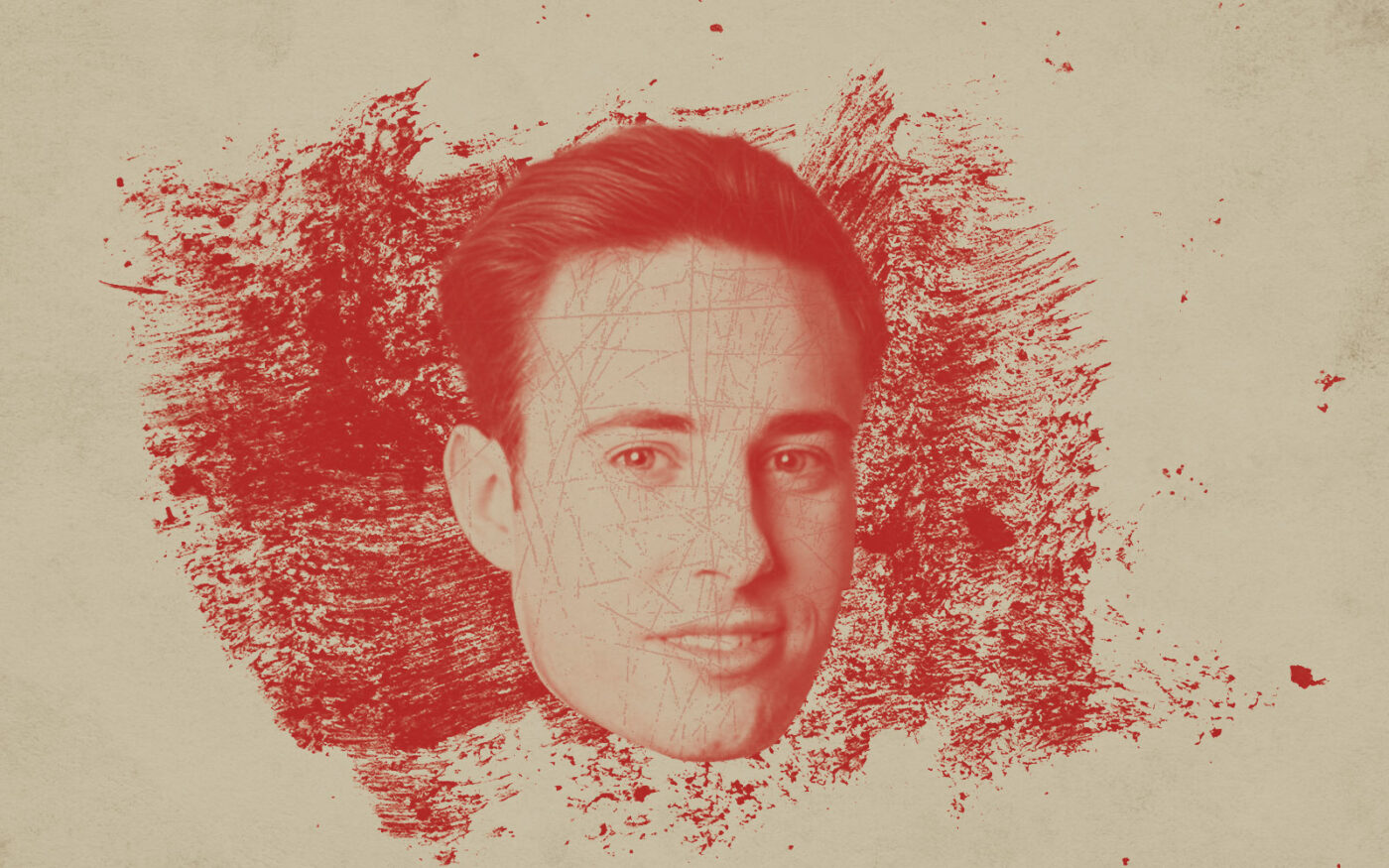

Eli Puretz wants others to avoid the mistake he made.

Puretz, a 29-year old real estate investor, is facing a sentence of five years in prison for his role in a multi-million-dollar commercial mortgage fraud.

Puretz pleaded guilty to one count of wire fraud this summer. His father and co-conspirator, Aron Puretz, was sentenced this month to the maximum of five years in prison.

In a surprise, the younger Puretz decided to speak openly about his crime with Lightstone Group’s David Lichtenstein on his podcast, Halacha Headlines.

People awaiting sentencing are usually advised by their lawyers to avoid speaking about their crimes. Puretz, however, offered some rare insight into what led him to commit fraud.

Eli Puretz said the fraudulent transaction that ultimately led the Department of Justice to bring charges against him was his first major real estate deal.

“I was wheeling and dealing as a typical bachur [Hebrew for young unmarried man] coming out of yeshiva and aggressively looking at real estate deals,” said Puretz.

Puretz said he would normally look to broker deals, but he saw an opportunity to “flip” a property. The goal of the fake flip was to buy and sell a property with no equity. Puretz, 24 at the time, claimed he was advised by others more seasoned than him.

Puretz, along with his father and Boruch Drillman, bought an office complex outside of Detroit for $42.7 million in 2020, but presented a fake sales price to a lender for $70 million. The lender used that inflated price to provide the co-conspirators with a $45 million loan, a larger loan than they would otherwise have received. Riverside Abstract, a Lakewood, New Jersey-based title insurer, performed two closings, one for the real transaction and one for the inflated sales price.

“My first real estate transaction, which was pretty large for someone my age, I committed something that was black-and-white bank fraud,” said Puretz.

“It is very unusual for a defendant, particularly in the vulnerable time between a plea and sentencing, to speak out publicly about his misdeeds,” said Sarah Krissoff, Eli Puretz’s counsel. “I’m proud of Eli for having the courage to come forward in an effort to deter other young people from embarking down the wrong path.”

On the podcast, Lichtenstein asked Puretz why he committed this act. Puretz pointed to his education, noting that young men in his community come out of the yeshiva system and seek instant success in nursing homes or real estate.

“They find themselves going from the yeshiva world to the bigger leagues at a very fast pace…and looking at that as being the barometer of success,” said Puretz.

Puretz said many of his discussions with his friends “sitting around the campfire” were about certain community members who had accumulated many nursing homes or real estate in a short period of time.

“Your judgment was clouded by the fact that everyone around you was making big moves around you so fast and so easy,” said Puretz. One is led to think, he said, that “there must be something that’s easy here.”

Puretz went on, “You’re seeing people that are just as young as me that joined the nursing home industry 24 months ago and today they are sitting on 50 nursing homes. All of this stuff clouds your judgment. It makes it seem very kosher to do the certain gray areas.”

Puretz did not mention during the podcast that his co-conspirator was his father. He also did not mention that his family’s companies have been accused of being slumlords across the country.

Eli Puretz has also found himself involved in another lawsuit in civil court with a former partner, Moshe Rothman, who sued him for $21 million. Rothman alleges Puretz was head of acquisitions for Apex Equity Group, the real estate firm led by Aron Puretz. (Eli Puretz has denied Rothman’s allegations in the lawsuit.)

The podcast interview detoured into other schemes, involving credit card points. Puretz said he went to a hearing recently where someone was sentenced over the illegal use of these points.

“Half of BMG [Beth Medrash Govoha Yeshiva in Lakewood] is doing stuff with credit cards,” said Puretz. “Some of it is kosher and some of it is not.”

Puretz said his first real estate deal was an instant rush.

“It’s a drug. You are tasting money and tasting real estate transaction at a very fast pace.”

He said it was hard to pull away from this feeling, and suggested that if he were not charged in the Troy Technology deal he could have dug himself deeper and found himself in a worse position later in life.

“I’m almost relieved that I’ve been hit with what I’m dealing with,” said Puretz.

Lichtenstein noted that he taught classes about real estate modeling to students like Puretz.

Puretz acknowledged that he took Lichtenstein’s classes and he was eager to learn about real estate. He said interest and ambition to learn are not the issue — instead, it’s lack of good mentorship.

“Most of us are being mentored by the wheelers and dealers, [who] are not necessarily mentoring us in the right way,” said Puretz.

“Most of us are dealing with people that are just okay bending truths and bending legality and doing these [deals that] are not very gray, but slightly gray. And from light gray to dark gray goes very fast.”

Read more