Where there’s a will, there’s a way — and there’s certainly a will to evade New York City’s imminent broker fee law.

As for the way, finding it might not be difficult.

“If landlords and/or brokers use secret arrangements to get around the bill, how would that ever be proven?” asks Jesse Rhinier, a Compass broker who was part of a core group of opponents of the bill, which becomes law Monday.

“I’m not saying I would do this, but I’m saying that I know from many conversations with many top rental agents, managers, and other landlords that this is actually what’s going to happen,” he said. “Landlords who don’t want to pay broker fees are not going to allow themselves to be forced to do so.”

The concept of the law, which City Council member Chi Ossé championed, is simple: Whoever hires the broker, pays the fee.

Enforcement, however, could be complicated.

Ossé’s FARE Act deems a broker who lists an apartment to have been hired by the landlord. But what if a broker advertises an apartment without identifying it? How could it be traced to the owner?

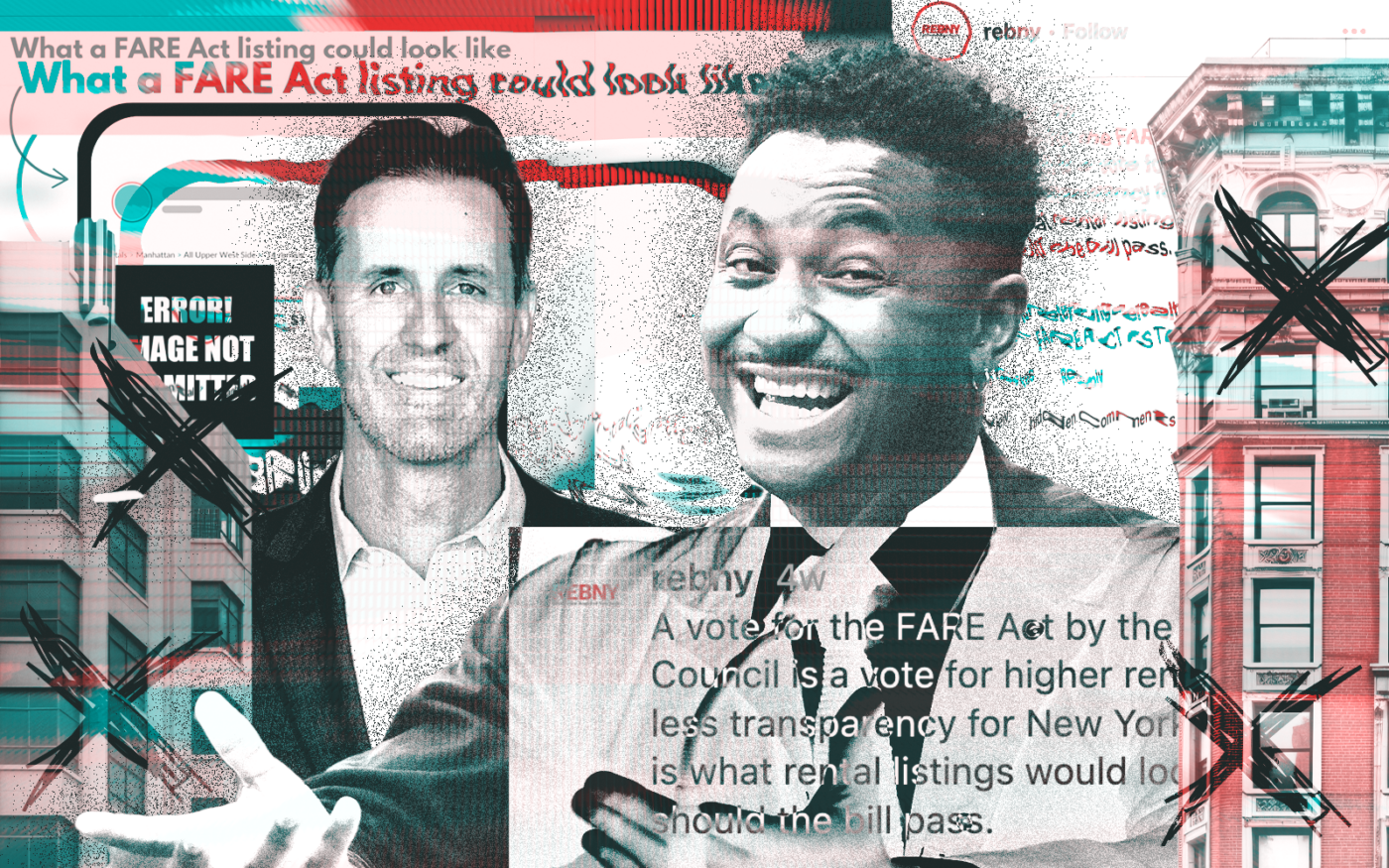

Before the City Council passed the bill, the Real Estate Board of New York posted on Instagram “What a FARE Act listing could look like.” The intentionally vague ad described an apartment “bigger than a toaster, smaller than a subway car” between Central Park West and the Hudson River, with rent between $1,000 and $8,000.

“I promise this apartment exists,” the mock listing said. “Give me a call if you want to see it.”

For good measure, it added a wink emoji.

The social media post, which Rhinier said he suggested, aimed to show that the FARE Act would reduce transparency. But it sure looks like a road map to get around the law, which takes effect in 180 days. (Friday was the mayor’s last day to sign or veto the bill, but he chose to do neither.)

A landlord could just inform brokers of available apartments without a paper trail. It’s hard to see how tenants could find those units without contacting a broker, then agreeing to be represented and to pay a fee at lease-signing.

“Given the deep pockets and considerable political power of the New York City real estate industry, it’s always a concern that they’ll search for ways to maintain the current system,” Legal Services NYC’s Jeremiah Schlotman said via email.

“If landlords take the tact of actively hiding available units to force additional fees on prospective tenants, this would be a stark example of the economic realities of today,” he added, citing the struggles of the working class. “Though this might be an area of potential litigation, it clearly flouts the purpose behind this law and would demonstrate unprecedented levels of avarice.”

In theory, a landlord could fetch a higher rent if a unit’s exact location and details were advertised, because it would attract more interest. The higher rent might justify paying a broker to market and show the unit.

In practice, landlords who have never paid broker fees will resist doing so, rather than vie for the hypothetical higher rent that advertising might yield. Ossé, whose bill became law 30 days after passage because the mayor did not sign it, declined to comment for this story.

For his part, Rhinier doesn’t think the “advertising = hiring” provision of the bill would survive a court challenge.

“But even if it did, broker fee listings would then just be all off market,” he said. “There would be a huge black market, and there are still many ways to rent such apartments, in particular easy-to-rent stabilized listings.”

Rent-stabilized units that can only be rented for far below market value will be a problem for the FARE Act. Landlords cannot reap higher rents for such units by marketing them to increase demand, which is sky-high anyway. These units will be rented exclusively by word-of-mouth, and brokers will have leverage to charge potential tenants high fees.

“Under the FARE Act, such apartments would NEVER be advertised,” Rhinier emailed. “They would still all be broker-fee apartments, and would all be part of the underground, black market that the FARE Act would create.”

How the city could stop brokers from kicking back some of their fee to a landlord is anyone’s guess. Even if the landlord doesn’t request a kickback, a broker might well offer one, figuring it will lead to more whisper listings from the landlord.

Read more

It’s also in the tenant’s interest to pay a fee for these below-market units, because those leases are so valuable.

When all three parties — tenants, brokers and landlords — have an incentive to do something, it will happen, FARE Act or no FARE Act.