City leaders learn landlord rules like many property owners do: the hard way.

After The Real Deal reported on five city officials — Mayor Eric Adams, Public Advocate Jumanne Williams and three Council members — with violations at their properties, all but one quickly cleared them.

The infractions ranged from insignificant (not filing annual bed bug reports) to serious (failing to pay property taxes), and in some cases had lingered for years. In following up on the story, TRD also found one statewide elected official lacked a pristine rental-property record.

Adams and Council member Crystal Hudson took care of the unfiled bed bug reports at their Brooklyn properties following TRD’s report. Hudson and Williams also addressed their failure to register their properties, as is required annually — with a form signed in ink.

The public advocate also paid an outstanding $300 sanitation fee from three years ago.

One case, involving Council member Gale Brewer, highlights the intricacies of property ownership in the city.

Brewer allegedly failed to secure a certificate of occupancy to legitimize her Upper West Side building as a single-family home. The city says it was once a single-room occupancy, even though its own land use map supports her argument that it wasn’t.

Still, Brewer faces a $2,500 fine if she loses in court. “I can see how frustrated people get about these things,” she previously told TRD.

If Darlene Mealy is frustrated, she is not saying. Despite TRD’s initial article and requests for comment, the Council member has neither commented on nor paid her $6,000 in outstanding property taxes at 1447 East 108th Street in Brooklyn.

Failure to pay could lead to a tax lien being sold to a private debt collector who could eventually foreclose, although Mealy and her Council colleagues would first have to reauthorize those auctions.

One of the mundane tasks that must be completed each year for multiple dwellings is submission of a signed property registration form to the Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

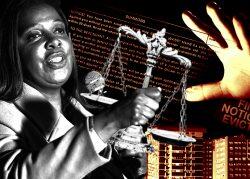

New York’s Attorney General, Letitia James, did that for her building at 296 Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn, but failed to pay the $13 registration fee to the Department of Finance by the July 1 due date.

James also failed to submit her annual bed bug report for 2023.

A spokesperson for the attorney general said both issues have since been addressed. But a third issue remained: Her building had two landmarks violations from 1995.

Such violations usually occur when the owner of a historic property alters something visible from the street without following Landmarks law, often by not securing a permit, and is ratted out by a neighbor.

Although James appears to have purchased the property in 2001 — six years after the violation — the responsibility to clear it falls to her. After an inquiry by TRD, the Landmarks Preservation Commission quickly investigated and dismissed the violations on the attorney general’s rowhouse. A spokesperson said one violation had been corrected by permitted work, but the city never removed it. The second violation also disappeared from the property’s records Wednesday, with the comment “duplicate” left in its place.

The commission’s Enforcement Fact Sheet says the agency frequently works with owners whose violations precede them.

In most cases, an owner can correct a violation by acquiring a permit from the commission that retroactively legalizes the work or by getting a permit and correcting the problem. Permits often require submitting professional drawings, photographs and a description of the work to be performed — and in some cases, a hearing.

The process can deter owners from fixing violations, although James likely was never notified of the infractions during her nearly 30 years of owning the Clinton Hill brownstone.

Landmarks violations are among many black marks on a building that do not trigger regular, or even occasional, notices from the city. They simply remain attached to the property’s public record, which anyone with internet access can view.

Nor do such unpaid penalties accrue interest or prevent owners from renting, borrowing against or selling their properties. As a result, more than $2 billion in fines goes unpaid, intentionally or otherwise.

Read more