Some New York developers aren’t playing the waiting game for 421a, the expired tax break that lawmakers just failed again to replace.

While project filings have steadily declined since the popular multifamily abatement ended a year ago and its 2026 completion deadline draws nearer, some developers are still filing permits to build rentals.

In April, developers filed 22 permits for multifamily building foundations to support 569 future apartments, according to Department of Buildings data compiled by the Real Estate Board of New York.

Two projects account for 487 of those units: a five-story, 101-unit building at 6014 Beach Channel Drive in Arverne, Queens, and a larger development at 12096 Flatlands Avenue in East New York.

The latter is the first piece of Innovative Urban Village, a 13-building, 100 percent affordable complex expected to add 2,100 units to the area.

Looking at the numbers, Joe Kohl Riggs, a principal at the Hudson Companies, speculated that many of the recent filings are tapping into other tax exemption programs. The Arverne and East New York projects, for example, are getting city financing.

Elsewhere, developers seem to be tapping into private revenue streams in order to break ground on small rental projects.

“There’s at least a couple of examples of developers actually going forward with private rental sites that we’re aware of,” Riggs said. These tend to be luxury rentals, which have enough profit margin to overcome their tax disadvantages.

Industry leaders have long touted 421a as essential for the vast majority of multifamily development in the city, because property taxes on rentals are otherwise much higher than for condominiums, which enjoy a permanent tax abatement.

To that end, the small-scale project recently filed could eventually be built as condominiums. A Manhattan Institute report last month noted that because of the favorable tax treatment, most developments with 11 or more units will be condominiums.

“The only other explanation that really makes a lot of sense to me is some of these are probably intended to be small condo projects,” Riggs said of the non-421a filings.

Tracey Appelbaum, a co-founder and managing principal at BedRock Real Estate Partners, one of the developers behind the $2 billion, 3,200-unit Innovation QNS in Astoria, insisted that most projects, let alone affordable ones, don’t make sense without the tax abatement — including her own.

“Even with 100 percent market-rate rentals and no affordable housing, with full taxes, it’s really hard right now to get anything to pencil,” said Appelbaum.

Without 421a, she noted, “Innovation QNS can’t be built in its current form.” Because it benefited from a rezoning, city law requires it to be at least 25 percent affordable.

The smattering of post-421a filings, however, suggested some unusual circumstances.

One possibility is developers who have owned a piece of land for a long time and don’t have to make up for a large acquisition cost.

“That someone can build less expensively and throw up, you know, 20 or 30 units,” Appelbaum said. “But no one’s building 200 to 500 units.”

“Or you may have someone who’s already had a footing in [prior to 421a’s expiration] who thinks that they can make that [2026 construction] deadline,” Appelbaum said.

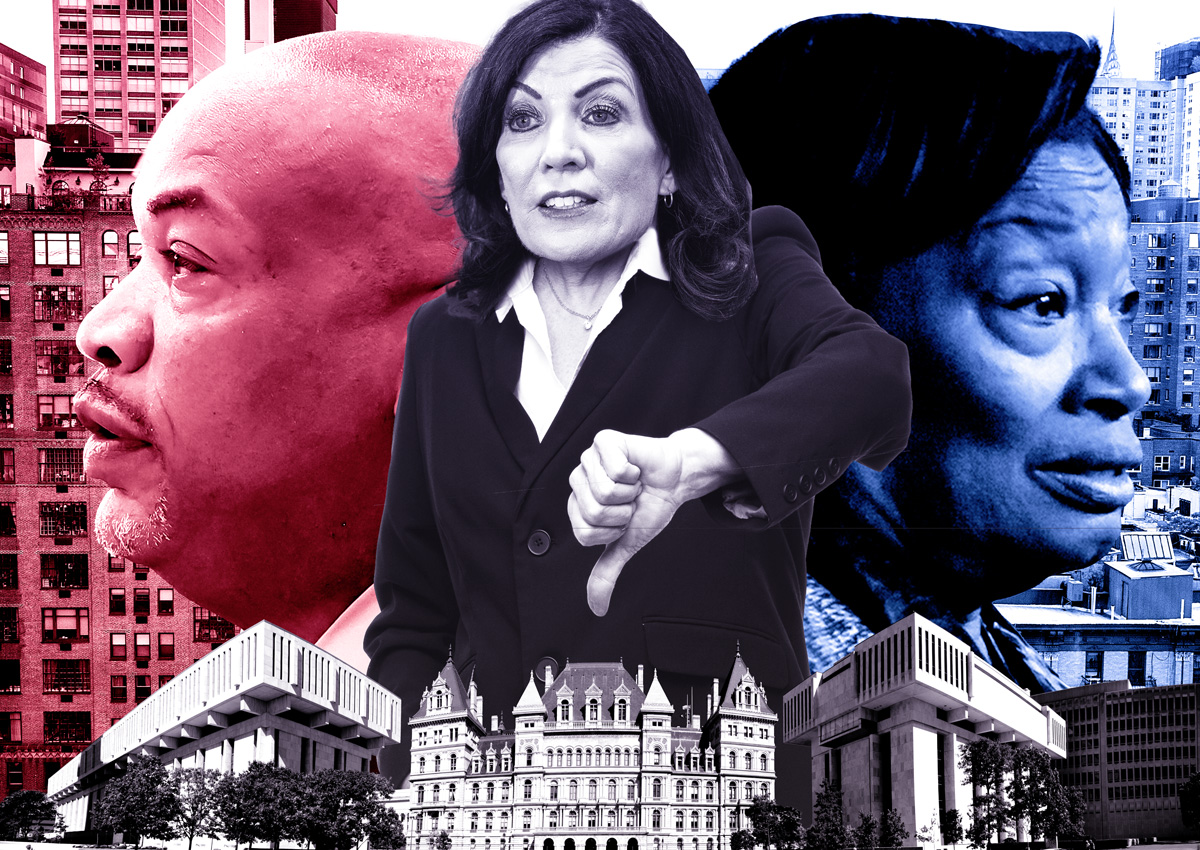

The state legislature and Gov. Kathy Hochul could not come to terms on a last-minute housing package that included an extension to the 421a construction deadline. The governor supports extending the deadline as well as implementing a new tax break, but legislators are divided.

Unless the governor calls reels legislators back to Albany for a special session, it will be the last chance to pass housing bills until January.

Read more

“All of this nonsense arises because our [property] tax policy is screwed up and we’re under-supplied,” Appelbaum said.

“I mean, you can slice and dice and explain and beg and choose and scream and yell and point,” the developer added. “But at the end of the day, we have a terrible tax system. And we need more housing. And it’s as simple as that.”