Glen Wolyner knew he was way behind on his property taxes. The debt had snowballed after a perfect storm that included a cancer diagnosis and a steep drop in his consulting work during the pandemic.

But he did not realize that the city sold his debt in 2021 and that the buyer was moving to take over his Soho loft.

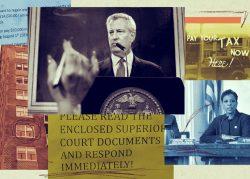

Then Wolyner received a notice last month: “YOU ARE IN DANGER OF LOSING YOUR HOME.” He owed nearly $300,000 and would need to pay 18 percent interest to avoid foreclosure on his apartment at 505 Greenwich Street.

“I think the mob charges less,” Wolyner joked.

His condo, which he bought for $2 million in 2010, was one of more than 360 properties in the city’s December 2021 lien sale.

When an owner fails to pay property taxes, the city sells the debt to an investment trust, which begins charging hefty interest. If the trust cannot collect the balance, it takes the property. The city began selling liens to the private sector during the Giuliani administration rather than foreclosing on properties itself.

Wolyner thought he had avoided the lien sale by entering a payment plan with the city, but the Department of Finance found no record of such a plan, a spokesperson for the city agency said.

Now Wolyner is trying to avert foreclosure and get a loan to pay his tax bill. He doesn’t deny responsibility — “I am not trying to dodge taxes or anything,” he said — but takes issue with the system.

“The whole process has been very, very opaque,” Wolyner said. “I can’t get an answer out of anybody.”

The lien sale, which includes properties that have long-overdue property taxes, water and sewer bills, typically yields tens of millions of dollars for the city. That’s a tiny fraction of its property tax revenue, but more than it would collect by merely mailing bills to those delinquent owners.

But the lien sale was unpopular with many politicians and was suspended during the pandemic, first by the city and then the state. The City Council reluctantly renewed the sale for one year — instead of the usual four — in January 2021, and exempted some properties. The sale that December has been the only one since then.

The Council also mandated that a 12-person task force make recommendations for reform. In November 2021 the group suggested the city stop selling liens on co-op and condo units and on one- to three-family buildings.

The task force also proposed creating a land bank that would collect debts and still use “outside servicing agents and securitized bonding as needed,” but have flexibility to work with delinquent owners.

Under another option, the city would forgive debt on a property transferred to a community land trust. The owner would then sign a ground lease with the trust, as well as a long-term agreement to keep the property affordable. The Abolish the Tax Lien Sale Coalition, a group of community land trusts, nonprofit developers and advocates, has pushed for such a framework.

By selling liens, “the city surrendered its leverage to move tax-delinquent properties into affordable housing programs or achieve other public policy goals,” a February report by the coalition stated. “The lien sale disproportionately harmed low-income homeowners and communities of color, contributing to predatory lending, foreclosures and the erosion of Black and brown wealth for decades.”

The city has not authorized another lien sale since 2021, nor has it adopted any of the reforms recommended by the task force. The Adams administration is still forming a plan.

“The administration is working to overhaul property tax enforcement to protect vulnerable homeowners and communities while ensuring that everyone fulfills their legal obligation,” a City Hall spokesperson said in a statement.

Wolyner is in a better position than some owners; even if he loses his luxury Soho loft, he has another home in Connecticut. But his case highlights a perennial complaint about the lien sale: That owners are not adequately notified before their property’s liens are sold and are sometimes confused about how to avoid foreclosure.

The Department of Finance mails repeated warnings, but sometimes it falls to individuals to rescue property owners.

Mariya Markh, a Brooklyn district leader and long-time City Council staffer, is known in some circles as the “Queen of Liens.” She estimates that she has helped more than 500 properties escape the lien sale since 2010.

Owners who reach out are often in financial trouble, she said, though some end up facing the lien sale because of a clerical error. Some think they are safe because they applied for a payment plan with the city and even sent a payment. They do not realize that extra steps are involved.

“I have run into folks who have said, ‘I think I’m on a payment plan,’ and then we look, and, “No, you’re not,” she said.

“That is the scariest thing about the lien sale for the average person,” she said. “When you are thinking there is no problem at all.”

Read more