The battle between New York City’s retail industry and street vendors has long been a lopsided contest.

Think Harlem Globetrotters versus Washington Generals, with business leaders dribbling, passing and scoring with ease while street vendor representatives haplessly chase after the ball.

But yesterday, all that changed. The vendors won. The Generals finally beat the Globetrotters.

They got the City Council to pass a measure that has been pushed repeatedly over many years, only to be beaten back each time by business improvement districts and restaurant and merchant groups. The vote was 34 in favor, 13 opposed. Starting in July 2022, the city will issue 400 new food-vending permits annually for 10 years, more than doubling the current total of 3,000, which has been capped since 1983.

Read more

One reason the business lobby had always prevailed is that it’s wealthier and better connected than the vendors, who have a tiny group called the Street Vendor Project. The BIDs, funded by a property tax surcharge, lobby for retail landlords. Some have budgets in the millions of dollars. The vendor group has six employees and two interns.

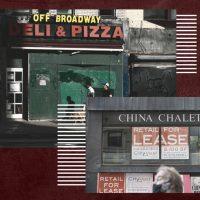

Also, many City Council members were receptive to the industry’s argument that street vendors take away sales from small businesses. Politicians don’t mind a corner without a street vendor, but hate to see cavities on commercial corridors where restaurants and food stores used to be.

That said, politicians have also been sympathetic to vendors, who are almost entirely immigrants putting in long, exhausting shifts to feed their families. But let’s face it: No one’s going to win an election by saying they sided with vendors over corner stores.

Consider Robert Cornegy Jr., a City Council member who stood with vendors on the steps of City Hall as a sponsor of their bill. Now, as a candidate for Brooklyn borough president, he’s against it. (His rationale: Covid. Never mind that the pandemic will be over before the new law has any impact.)

To be sure, another 4,000 vendors in a city of 8.4 million people — one vendor for every 2,100 New Yorkers, not including tourists — will not fundamentally change the economy or force shopkeepers to close. Opponents’ predictions of doom, which preceded the coronavirus, were always overblown.

But the bill will not end the street vendor problem that has plagued city policymakers for ages: the black market.

As every economist knows, when the government sells a limited quantity of something valuable at an artificially low price, and forbids reselling it, a black market will form and people will sell it there.

That’s what happened with food-vending permits.

The city issued the 3,000 permits and made them renewable every two years for $200. Applicants gobbled them up and now lease them to vendors for, say, $24,000. Some permit holders have long left New York, or the U.S. entirely; they use brokers to handle the transactions. All the permit holders have to do is return every two years to renew.

This is illegal, but unenforceable. If an inspector asks a vendor who the permit holder is, the vendor says, “It’s my partner” or “it’s my cousin.” The vendor never rats out the permit holder because if the permit were revoked, the vendor would be out of a job (and probably any unpaid “rent”).

The city could have created a legal, functioning market for permits, as it did for taxi medallions in the 1930s, but it never did. Thus, your favorite vendors and food trucks are leasing permits in this illegal, unregulated system. They have no choice.

The Street Vendor Project says the legislation solves this conundrum by requiring the new permit holders to be present at their food cart or truck. The original $200 permits will be converted to must-be-present permits by 2032, giving today’s permit renters 12 years to get one of the 4,000 new permits (only 1,000 of which may be used in Manhattan) or find a new line of work.

Will this end the cheating? It is hard to see how.

Manning a food cart is hard. Permit holders who cannot work from dawn to dusk, seven days a week, 52 weeks a year, will not want to give up revenue (or risk losing their prime location, which is protected by an honor system and by “muscle” hired by permit brokers). They will undoubtedly find someone else to stand in for them, especially if they need the money to pay the rent.

Is the city really going to revoke the permits of vendors caught doing this, depriving them of their livelihood? If inspectors turn a blind eye, the black market continues. If they don’t, vendors become jobless. It’s a lose-lose proposition.