Distressed debt fund managers aren’t the only ones smelling opportunity from a coming foreclosure crisis.

A nonprofit seeking to help the poor says rental properties’ struggles present a chance to decommodify multifamily buildings.

The Community Service Society, which looks for systemic solutions to problems that create a “permanent poverty class” in New York City, expects non-payment of rent to trigger a wave of apartment building foreclosures.

When that wave hits, the group argues in a report, the city and state should make sure rental housing does not fall into the hands of new profit-seeking investors — as it did after the financial crisis of 2008.

The report suggests policy makers study solutions developed in the last recession, including a “First Look” program developed with New York Community Bank and administered by the nonprofit Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development.

In 2012, that program resulted in the sale of four distressed mortgages to a nonprofit developer, but a foreclosure auction was held anyway and the nonprofit was outbid by a private investor. The buildings remain in disrepair.

To avoid that scenario, the report recommends the city expand programs such as land banks to finance preservation purchases, and suggests tenants be given the first opportunity to purchase a building, should it come up for sale.

The report also recommends eliminating the 421a and 485a new-development tax breaks and instead adopting tax policy that favors social housing models such as community land trusts.

The authors acknowledge that the biggest obstacle to the goals in the report: cost.

That sentiment echoed by Jay Martin, executive director of the Community Housing Improvement Program, which represents rent-stabilized landlords. Martin disagreed with the report’s recommendations, which he said stem from the idea that profit from housing is wrong.

The report does not answer fundamental questions about how to transition to social housing, Martin said, such as: “How do we pay for it? How do we bring housing costs down, and how do you replace all the tax revenue?”

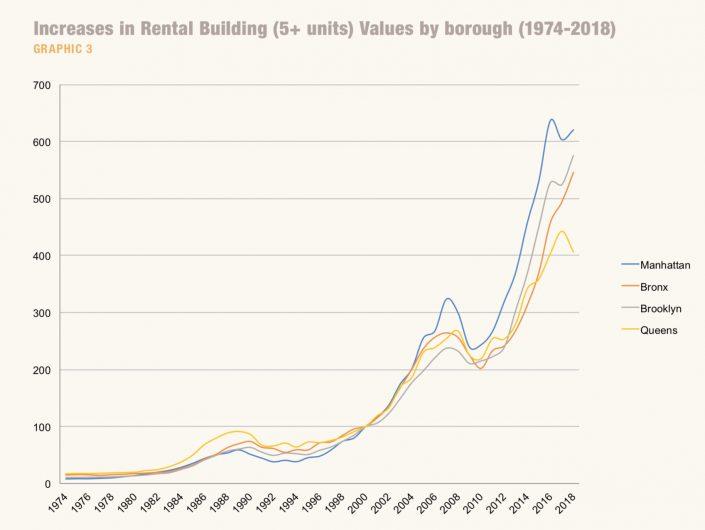

Martin noted that the city depends disproportionately on tax revenue from rental buildings — a feature of overreliance on real estate to pay for social services, after urban disinvestment in the 1970s, the report argues — and that the city is already facing a huge budget shortfall.

Despite the heavy toll the virus has taken on New York City — and early predictions that tenants would skip rent and landlords would miss property tax payments — the rental market has fared much better than other sectors. It is unclear how much multifamily distress there will actually be.

Landlords say they have gotten no help during the pandemic, but their finances are being steadily depleted.

“It’s almost worse than a complete crash,” said Martin. “We’re in a slow bleed period, with buildings operating on a tenuous margin.”

Jerry Waxenberg, who owns a significant number of rental buildings in the Bronx, said rent collection has been steadier than he expected.

“We operate properties in some of the poorest sections in the city and our rent collections percentage is among the highest,” said Waxenberg.

The lack of severe distress helps explain why legislative efforts to cancel rent, or expand a means-tested federal voucher program, as landlords prefer, have gained little traction.

Despite U.S. Census findings that 15 percent of tenants were not current on their rent in October, industry reports have found that collection has been fairly strong. Although landlords have said that rent strikes have had an impact, it is unclear how much of a rent shortfall is attributable to them.

Meanwhile, landlords are paying their mortgages. Community banks in New York City — the go-to lenders for the rent-regulated multifamily market — have not reported widespread delinquencies.

Nevertheless, unemployment figures in New York City remain much higher than the national average, and while tenants may make tradeoffs to keep paying rent, a prolonged crisis could lead to foreclosures across all asset classes — including multifamily.

The Community Service Society report takes issue with the city relying on increasing property values for tax revenue. It also criticizes the investment strategy of raising rents and neglecting properties to raise net operating income.

“This report seems to insinuate that every landlord has done that,” said Martin. “But there’s no measurement out there, that I know of, that people making more money leads to investing less in the property.”