Some real estate players are known for what they build, others for what they own. Then there’s Joseph Tabak, who without a portfolio of trophy properties or any ground-up projects of note has become one of the most highly regarded dealmakers in the business.

With a penchant for structuring debt and equity deals and assembling parcels for sale, Tabak has left his imprint on more than $13 billion worth of transactions over this three-decade plus career — most notoriously, the Ring portfolio in Midtown South. That deal, which has acquired near-mythic status among industry insiders, had a colorful cast of characters including Extell Development’s Gary Barnett, the Chetrit Group’s Joseph Chetrit, the stubborn brothers Frank and Michael Ring and Tabak’s sibling, Eli Tabak.

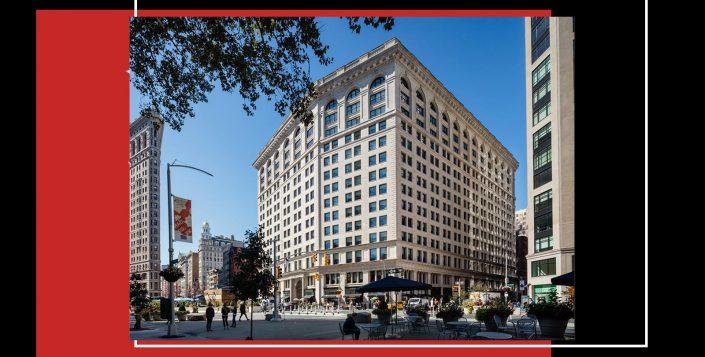

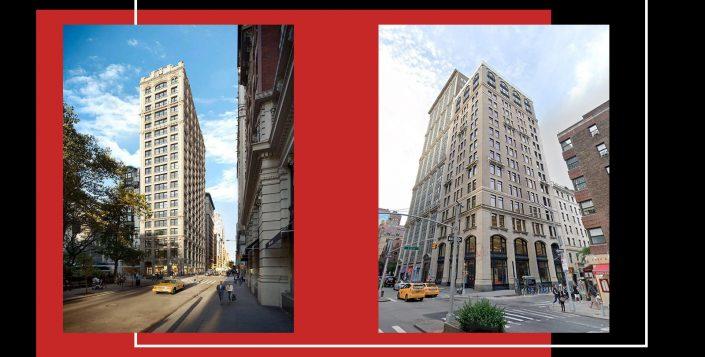

Along with Robert Wolf’s Read Property Group, Tabak put together the land for what is perhaps Bushwick’s most ambitious residential project, the Rheingold Brewery redevelopment. With Chetrit, he sold the International Toy Center buildings for a collective $715 million in 2007, more than twice what the partners had paid just two years earlier. (He later had a bitter and highly public falling out with Chetrit over the Ring portfolio) . In 2013, Tabak even made a play for the Empire State Building.

International Toy Center at 200 5th Avenue (L&L Holding)

Known among his New York contemporaries as the “real estate doctor,” Tabak, the chairman of Princeton Real Estate Partners, regularly counsels everyone from All Year Management’s Yoel Goldman to Extell’s Barnett. In one of the first-ever in-depth interviews of his career, he sits down with The Real Deal to discuss his approach to dealmaking, the “brain damage” he suffered in his battle for the Ring portfolio, and what keeps him going in the business.

I know a lot of top developers come to you for advice. Where did you pick your stuff up?

I started off in real estate management and then went into buying my own small deals and growing from there. I’m just an analytical guy. A guy could be talking to both of us at the same time, saying the same thing, and I hear something different. I could sometimes make a mistake in a deal, it can happen – thank God it very rarely happens. But when I have a conversation, I’m not going to say something stupid.

Before I say something I think to myself: “Where am I right now and where am I going to be right after I say what I want to say?” I’m only going to say it if I’m going to be in a better spot. So automatically, two-thirds of what most people say, I don’t say.

A rendering of Rheingold Brewery (ODA Architecture)

From the Rheingold Brewery to the Ring portfolio to the Ritz Plaza, your mark is on all these properties in interesting ways. You’re one of those classic New York real estate deal junkies.

There are deal junkies that just buy everything. I’m actually a deal junkie that just enjoys the real estate business. I like the challenge of it. I usually come up with structures — a lot of people look at deals and don’t find the value, or the value is there and you can’t realize it.

Let’s talk about the Ring portfolio. That ranks among Gary Barnett’s favorite and most lucrative deals. I know you came in from the Michael Ring side of things.

Extell Development’s Gary Barnett

Right, I came in from the Michael Ring side, knowing I had a statutory right because it [the 14-building portfolio] was owned in TICs [tenancy-in-common, a form of deal structure in which property ownership rights are shared.] You can use that in court to force a sale or some sort of, “I buy you or you buy me.” Michael at the time wanted to get his hands on $100 million.

Over the years, people call me and they say, “Joe, I have a deal, would you like to buy this deal?” It’s a six cap, it’s got upside. Great deal.” I say, “Why don’t we get together?

I analyze the deal. I rely on what I analyzed and I don’t think he understands his own real estate better than I do. I want to know his story: Why is he selling? My partners used to say, “You got a great deal, what are you climbing into the guy’s life for? Get the deal done.” But when you find out why the guy wants to sell, that could enhance the value of the deal tremendously. For example, a guy comes to you and says he’s selling. He bought [the property] for $10 million 10 years ago, and he’s selling it for $60 million. He’s making a $50 million profit. So, [I ask] why are you selling the deal?

He says, “Well I need $20 million to buy a yacht,” or whatever it is. So I say, “You don’t have to make a $50 million profit to buy a $20 million yacht. Why don’t you sell for just $20 million?” So either the guy says, “It’s my only asset,” or “My tax basis is so negative in this deal that for me to walk home with $20 million, I’ve got to sell this thing to you for 60, otherwise the rest of it is going to the IRS.” Now I know I have a perfect candidate. If I could tax structure that deal for him in many different ways — whether I do a lease with an option to buy and I refinance the fee position and give him $20 [million] as a refi — which is not taxable – and he got his 20, then I have an option to buy it any time down the road.

You figure out the pain point.

Right. And all of a sudden you’re writing a $30 million check for a $60 million deal. That’s way better. Many, many years ago, I had a negotiation by phone with the owners of the Roosevelt Hotel.

My partners used to say, ‘You got a great deal, what are you climbing into the guy’s life for?’ But when you find out why the guy wants to sell, that could enhance the value of the deal tremendously.

With PIA [Pakistan International Airlines]? They just announced they’re closing the hotel permanently.

That’s an amazing piece of real estate. At that time, the price on the deal was $26 million. Hard to believe today. I actually flew to Karachi with my lawyer. When we got there they said, “Okay, so let’s do a deal.” And they gave us a contract. Instead of $26 million, it said $96 million.

Let’s back up: You flew to Karachi as a Jewish man. Any reservations?

It was a different world, there was no problem. First time I flew to Israel, I actually stopped in Iran on the way.

Anyway, I’m a young kid, they flew me out here, and I’m ready to jump all over them. My lawyer, Alan Pomerantz, put his hand on my lap and said, “Let me talk.”

He said something which at a very young age was a tremendous lesson: “Guys, you spoke about 26, now you’re at 96. My client doesn’t care what the price is. You pick the price, let him pick the terms.”

So, like my mother used to say, there’s a Polish lottery ticket: you win $1 million and they pay it out to you a dollar a year for the rest of your life. All you end up with is $60.

It showed you a deal doesn’t have to be looked at straight. You can look at it sideways, backwards, upside down. And that’s basically been your career.

Correct. Michael Ring wanted to give me 25 percent of the deal — which means 50 percent of his 50 percent TIC [stake] — for $100 million. He says, “I want to put aside $100 million for my family.” I said, “If I give you $100 million, you’re going to be taxed from here to wazoo because you owned this forever. [Instead], I will give you a loan against your TIC — the whole 50 percent TIC. You pay back the loan and I own 50 percent of the deal.”

Related story: “Ringing in” a new era: Will a legal battle unravel the coveted Ring portfolio?

I bought 50 percent of his TIC for $50 million instead of $100 million, because I gave him the $100 [million] against his entire share. He wants to keep 50 percent of [the deal] and he needs $100 million cash; I got both of them done for him. Without negotiating him, I brought him down to 50 percent of the price. So depending on how you slice it and dice it, the guy can end up with his result and your deal becomes twice as good.

So this happens and on the other side you’ve got another player who’s extremely creative, Gary Barnett. You’ve essentially become a hiccup in his plan.

Related story: Gary Barnett reveals how he won the Ring portfolio

Frank and Michael Ring

I had a choice, to go to Frank or Michael. I just felt I’ll have an easier time dealing with Michael than Frank.

They were both known to be quite difficult.

Yes. But out of the two, Frank wins, so I decided to deal with Michael. Gary was dealing with Frank, which was a much much harder nut to crack and way more expensive. I think he must have paid [Frank] six times more than I paid for my piece. It doesn’t make a difference if I own the other 50 percent. [Gary] was going to do the dissolution [of the TIC] anyway. I was done, I had my piece. He could come to me, pay me more because I really got my deal cheap. And he did.

But it got messy. There was a very contentious lawsuit with Joseph Chetrit.

Related story: “Ring a ding ding boys”: Behind Chetrit’s Ring portfolio beef with Princeton Holdings

Joseph Chetrit (Getty)

Before I had a deal with Gary, Joe joined in on the deal and he gave us a heavy markup — I think it was about a $46 million valuation markup. We took him in and I went ahead and sold it to Gary. Then there was an issue between us [and Chetrit] about what he’s entitled to and what I’m entitled to. It all went away and everything is fine and dandy.

When you go into these messy transactions, sometimes you’re up for a fight. It’s quite hard not to take personally. How do you navigate such disputes, and do they dissuade you from doing these hairy deals?

I buy real estate every morning when I wake up. Whatever the value is today, if I don’t sell it at that number, it means I’m a buyer at that number.

First of all, 95 percent of my deals are not hairy. They’re complicated. I’ve never dealt with a Ring prior to Ring. I did well over $1 billion of business with Joe Chetrit. 450 West 33rd, we bought together, the Toy buildings, we bought together. We did very well, never had a fight. If I would have seen that [the Ring portfolio dispute] coming, I never would have brought him in as a partner. If I would have known that part of what I need to underwrite in this deal is that brain damage that I went through for a bunch of years, I wouldn’t have done it.

212 Fifth Avenue and 251 Park Avenue South, part of the Ring portfolio (Sotheby’s, Google Maps)

You’re more of a structured transaction person. Development was never your thing, is that fair to say?

Depends what you call development. Most of my portfolio we owned for a long time. We lease it up, we upgrade it. I’m not a ground-up guy, that’s not the business that I’m in, but there is a very long play of real estate. And it’s very hard to calculate.

You take a guy that makes $3, $4 million clip. Put in $10 million, made $84 million. Nobody takes that $84 million and puts it in a safe deposit box. You work that money and you make another 30 and another 50. Another guy says, “Hey I want to go in for the long haul.” He goes and repositions the buildings and he condos it or he leases it and then boom, a bad market comes. Who’s ahead of who at the end of the day? I don’t know.

If I would have known that part of what I need to underwrite in this deal is that brain damage, I wouldn’t have done it.

We bought 450 West 33rd, I believe we paid $280 million and we sold it in 2007 for $700 million to Broadway Management. Everybody said, “Don’t sell it, hold on to it.”

I have a very interesting rule in real estate: You tell a guy, “I’ll buy your building for $700 million.” He says, “I don’t want to sell it.” When that situation comes to me and my partner says he doesn’t want to sell, I say, “Okay. You wouldn’t sell it for $700 million – would you buy it for $700 million?” Usually the answer’s going to be no. I say, “Hey, a guy is sitting in your office and put a check on your table for $700 million. When you pick up that check and give it back to him, you know what you just did? You just bought your building for $700 million.”

So I buy real estate every morning when I wake up. Whatever the value is today, if I don’t sell it at that number, it means I’m a buyer at that number. The only caveat of that is tax.

You’re indirectly responsible for this super-gentrification of South Brooklyn. That specific asset class — big, pricey rentals stacked with amenities — is in trouble post-Covid. A lot of those deals are underwritten at very high rents, so the banks will have to come to terms with the Goldmans [Yoel Goldman of All Year Management] and Rabskys [Simon Dushinsky and Isaac Rabinowitz] of the world. Is there going to be pain?

It’s really deal by deal. A lot of the pain is going to be for the institutions and the banks that lent the money, whether they’re going to make a deal with the landlord and bring the numbers down or bring the interest down to a low enough number to keep this thing alive. Some of the lenders actually that are repo’ing and they’re financing because interest rates are so low right now, they could put themselves in a better position where they could sell off a 60 or 70 percent piece of their loan at a really cheap number, leaving them enough room to be able to drop down the landlords’ payments to a number that still keeps them going.

We are now in the period where you don’t see many transactions going on. The bank is not ready to write it off, the landlord is not ready to tell his investors “You guys are history.” So people are not buying, people are not selling and it’s just stuck. The only transactions you’ve seen are the REITs or the debt funds that actually have debt that they have to pay off – they have an incentive to sell stuff at a discount just to get cash in the door.

Another big shift that’s happened is this leftward movement in terms of rent reform and politics. How do you think that’ll shake out and what does that mean for your business?

There’s a lawsuit going on that’s a flip of the coin. Chances are things are going to change, the government is not going to get everything they want, the landlords won’t get everything that they want. What’s really going to shake this thing out is as people that own rent-stabilized buildings are not making a living and don’t have enough money to fix up your property, tenants are going to feel that what the politicians hurt was the quality of living. Buildings are going to start getting dilapidated and that’s what happened in the ‘70s in the Bronx. Landlords are going to be stuck. They’re going to turn around, whether it’s to the city or the bank, and say, “Just take this off my hands because I can’t afford to be the Salvation Army.”

The rhetoric against the industry has become more confrontational over time and is actually affecting policy. What do you think the industry could have done differently?

There wasn’t a lot of dialogue going on before the law came out and there might have been some sort of a miscalculation where everybody thought there’s no way in hell this is ever happening. So all the lobbying and all the work came in a little too late. Nobody thought Cuomo would ever sign this and I guess Cuomo had to sign it because he’s controlled by these people. But right now, I don’t think coming in a more diplomatic way is going to get the law changed – the law is where it is. [The lobbying] should have been done before the law came out. It was a bad miscalculation by the entire industry.

Do you have a target dollar number in mind before retirement? You’re not a very extravagant guy — maybe you have an island I don’t know about.

I’m not a retirement type of guy and I don’t have a number in mind. Every kid that starts off in real estate says, “You know what, as soon as I have a million dollars, I’ll stop right there.” But as the bar goes up, especially if you enjoy what you’re doing, you keep on doing it. Hopefully you do good stuff with your money. I don’t have the lifestyle of yachts and planes and homes in the south of France.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

(Write to Hiten Samtani at hs@therealdeal.com. To check out more of The REInterview, a series of in-depth conversations with real estate leaders and newsmakers hosted by Hiten, click here.)