Janno Lieber kicked off the year eager to get started on an unprecedented $54 billion worth of capital projects for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

That’s all in jeopardy now, according to Lieber, the MTA’s president of construction and development, as the authority’s revenue has plummeted in the pandemic.

“We may have to cannibalize the capital program in order to keep the lights on to feed the operating budget, just so we can continue to operate the trains and buses and commuter railroad,” Lieber told The Real Deal in a live webinar Wednesday.

Projects in the plan that were poised to speed service and boost real estate values in the MTA’s 12-country coverage area, such as a new signal system and Metro-North stations in the Bronx, are effectively on hold as the agency boils its agenda down to safety-related work.

Read more

To address its worst-ever budget crunch, the MTA has been lobbying to get $12 billion in federal aid, making a case that without the emergency assistance, the authority would have to reduce service by 40 percent, which would be devastating for the metro area’s recovery.

Lieber, who came to the MTA from Silverstein Properties in 2017, said his development team has been trying to reduce spending by simplifying project designs and bundling projects to minimize the number of system shutdowns.

He has also sought to shrink the number of people who oversee a given project. The MTA is infamous for having too many chefs in the kitchen, resulting in decisions having to make their way through numerous levels of bureaucracy — sometimes to be changed at the final stage. That stretches out schedules, runs up costs and vexes contractors, who typically inflate bids on projects in anticipation of such delays.

Silverstein used small, nimble teams to rebuild the World Trade Center, said Lieber, who was instrumental in that effort and said he is applying its lessons to the transit agency.

The MTA is also trying to come up with better ways to finance projects including the Penn Station overhaul and expansion, said Lieber in a conversation with The Real Deal senior managing editor Erik Engquist on Wednesday’s TRD Talks Live.

One example is One Vanderbilt, a Midtown office tower that officially opened last month. Its developers, led by SL Green Realty, agreed to make $220 million in improvements to the adjacent subway station at Grand Central in exchange for the air rights to build the 67-floor skyscraper.

In other parts of Midtown East, the authority is working with building owners — such as JPMorgan Chase and Boston Properties — on transit infrastructure work near their properties, Lieber said. Those agreements are largely made possible by provisions of the area’s 2017 rezoning.

“But in the rest of the system, we really do need to figure out how to do what the rest of the world is doing, which is so-called ‘value capture,’” Lieber said, referring to tapping the real estate value created by transit improvements to help pay for the work.

The Bloomberg administration financed the No. 7 subway extension to Hudson Yards by issuing municipal tax increment financing bonds, which are being paid back through property tax payments from the area served by the extension. But the MTA lacks the capacity to do that without the city, and it has not been a priority for the de Blasio administration.

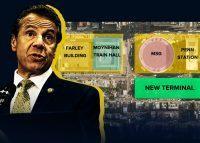

For the Penn Station expansion, teaming up with a private developer is an alternative. Gov. Andrew Cuomo wants to add eight new tracks underneath the block between Seventh and Eighth avenues and West 30th and West 31st streets.

The MTA, along with New Jersey Transit and Amtrak, would have to acquire the land, demolish existing buildings, excavate, and create an underground transit facility and ground-level entrances. Whatever is built above the tracks would play a major role in the project “because the main point is that the above-grade should be real estate, the privately developed real estate,” Lieber said. “So that you have the opportunity to generate income to pay for the station.”

But for now, the authority’s capital projects are mostly at the mercy of the federal government.

Out of its $54 billion capital plan, about $15 billion is to be funded by congestion pricing, which has been held up for about a year by the Trump administration, whose approval is needed.

The MTA has also been waiting for more than a year for the federal government to approve its grant appreciation for the second phase of the Second Avenue subway, which would connect the station at East 96th Street at Second Avenue with 125th Street in East Harlem, Lieber said.