When self-described real estate expert Stephen Gilpin first arrived in Manhattan, he was a Quaalude-popping blue jeans model. To make ends meet, he attended house parties of the wealthy, a handsome face for hire. It was dull work, and to distract himself Gilpin would contemplate the makings of the grand homes of his hosts. It was then, sometime in the 1990s, that Gilpin visited Trump Tower, where he was dazzled by “the sixty-foot high waterfall.”

“What an impressive place!” he writes. “I could feel the power and smell of money.”

Gilpin’s first book, “Trump U: The Inside Story of Trump University” is a chronicle of how one man went from posing for Levi Strauss to proselytizing for property at Trump University, the for-profit education venture launched in 2005 by Donald Trump. The book is Gilpin’s attempt to restore a reputation sullied by years of allegations about fraudulent practices at the business. But it’s also an indictment of one of the president’s most prominent ventures, one that was shut down after just five years, led to a $25 million settlement and continues to shape his public image.

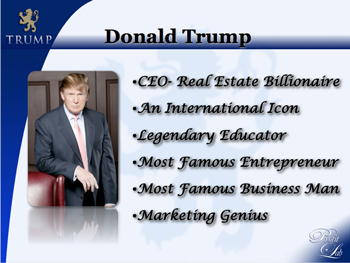

Trump University began with honest intentions, Gilpin writes. Business professors were tapped to design legitimate coursework. But it descended into a classic bait-and-switch scheme orchestrated by snake-oil salesmen, according to Gilpin: It reeled in the curious and unsavvy to free seminars, asked them to apply for hefty lines of credit, and then pressured them to buy ever-more expensive seminars and mentorships so they too could master of the art of the deal, just like Donald.

“Despite the creepy vibe, I was seduced,” Gilpin, who served as a student mentor and an auditor of sorts, writes. There were warning signs, he admits – early course material focused on “find[ing] homeowners who are in a truly desperate financial position.”

By 2007, Gilpin writes that the company had mostly ditched the real estate experts in favor of motivational speakers with little to no industry knowledge. The speakers pitched live events in which students, once they paid $1,495 for the privilege, would be “exposed to Trump’s personal secrets of real estate trading.” That’s despite Trump having little to no involvement in any of the “secrets” being shared, many of which amounted to untrue or even illegal business advice, Gilpin writes.

Performance was valued over substance and all instructors, regardless of marital status, were told to wear wedding bands to project an image of success and stability. “This was in keeping with the notion that the live events had but one purpose: to drain cash from the attendees.”

Dealing with instructors who didn’t know what they were talking about–and the students who complained about them–appears to have become Gilpin’s primary function (“I really believed that they wanted me to fix it”). One instance recounted in the book involves a retreat in Scottsdale, Arizona, where a student was instructed to do something called “clouding a title,” a tactic meant to discourage competing buyers of a property by filing a claim, thus calling into doubt whether or not the property was available for sale. This tactic is apparently illegal in Arizona, and the instructor, Steve Goff, was going through bankruptcy during his teaching stint, with much of his own debt tied to mortgages.

Gilpin also observed seminars hosted by James Harris, who claimed to be “one of the 12 top-producing brokers” in Manhattan. Harris, who was a convicted felon and whose ex-wife alleged he threatened to kill her during divorce proceedings, in fact had no experience selling real estate. Another instructor who worked through a licensee called Prosper Learning ran a Ponzi scheme shut down by the SEC, but not before he allegedly directed one Trump University student to invest $230,000 in an ill-fated Spanish real estate venture.

Some instructors left Trump University in disgust. Gilpin did not. Things only got stranger.

Sometime after Barack Obama’s 2008 election win, as Trump started thinking more seriously about a path to the White House, Gilpin says he was was recruited by the Trump Organization to help locate a copy of Obama’s original birth certificate, a quest that would become Trump’s cause célèbre and account for a significant portion of his cable news appearances for the next several years. Gilpin says he then managed to obtain such a copy, but received none of the promised reward. Trump then began his long campaign to spread doubt about Obama’s birthplace.

“The birther campaign highlighted what I knew of Donald Trump from my experience working at Trump University,” Gilpin writes, “in particular his penchant for creating parallel universes populated by ‘facts’ that conformed to whatever goal he was striving for at the moment.”

Although Gilpin says he was a prized employee (the book includes a scanned copy of an email Trump signed that thanks Gilpin for doing a “great job”), the Trump team eventually turned on him. In 2011, as what was left of Trump University faced mounting legal and financial problems, Trump’s personal attorney Michael Cohen accused Gilpin of stealing money from the enterprise. When Gilpin defended himself and claimed he was the one keeping Trump University from being shut down for fraud, Cohen reportedly “exploded.”

All instructors, regardless of marital status, were told to wear wedding bands to project an image of success and stability.

“Gilpin, what the fuck do you know? I’ll make sure you never fuck your spouse again! Got it?”

“Mr. Cohen, my spouse passed away a year ago,” Gilpin replied.

The Trump Organization’s general counsel, Alan Garten, didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story, nor did Cohen.

And yet, after all he had seen, when Trump University was sued by New York Attorney Eric Schneiderman in 2013 for, in Schneiderman’s words, “bilking students out of thousands of dollars”, Gilpin chose to side with Trump and testify on his behalf. He describes his willful cooperation like being some unwitting victim of hypnosis.

“They questioned me under duress,” Gilpin writes of the rigorous deposition prep with Trump’s attorneys, “creating a stressful situation and then asking me questions over and over again, feeding me answers until I started to doubt what reality was… I started to believe I didn’t know anything for sure.”

This explanation may prove unsatisfactory to readers who hold on long enough to make it to the end of the book, but if Gilpin’s personal experiences were given more space, perhaps such appeals for sympathy would be more effective. Throughout, Gilpin relies heavily on the work of investigative reporters in national newspapers and his own firsthand observations are often secondary to retellings of stories already recounted elsewhere.

Whether the book succeeds in clearing Gilpin’s name—which he has publicly said was his primary purpose for writing it—will not be of primary concern to most readers, who will likely look to it as another window into the president’s shadowy business empire. But Gilpin, the “white knight” in this story, would hardly be the first New York real estate man with an inflated sense of his own significance.