The federal formula used to determine affordable housing requirements in New York City actually includes income statistics from Westchester, Rockland and Putnam counties, and critics say it’s helping put affordable housing out of reach for scores of city residents.

But there’s another approach that may be gaining momentum, and proponents think it might make building affordable housing a more attractive prospect for developers.

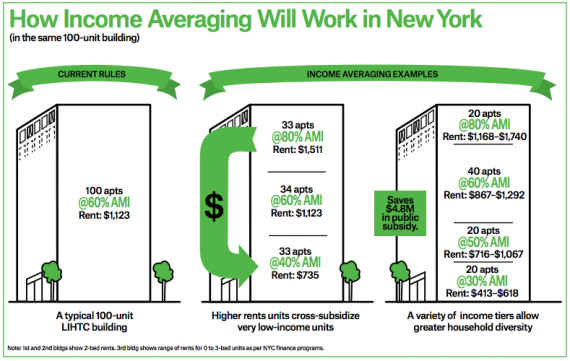

The proposal, known as income averaging, would allow developers to set aside units for wealthier tenants, whose rents would help subsidize lower-income tenants.

It could create more rentals units with deeper affordability, advocates say.

Here’s how the system currently works: The federal government calculates a statistic called area median income, or AMI, which is then used to set affordability standards for some projects, including those taking federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). But the formula that calculates AMI includes incomes from those counties in upstate New York.

Critics say that this formula puts affordable rents at levels out of reach for city residents where local median income is much lower. “Affordable,” according to AMI, may not actually be affordable to those in certain communities.

But income averaging could help alleviate some of this affordable housing burden, supporters say. It would utilize the current AMI calculations, but would increase affordability through tweaks to the LIHTC program, which has helped finance over 75,000 units of low-income housing in the city between 2005 and 2014.

While the current LIHTC system sets a 60 percent AMI limit for units receiving credits ($54,360 for a family of four in 2016), income averaging allows buildings to have tenants whose income exceeds that limit – as long as units receiving credits average incomes at or below 60 percent.

“Most of the housing in the tax credit program gets created just below 60 percent,” said Rachel Fee, executive director of New York Housing Conference (NYHC), an affordable housing nonprofit that supports income averaging. The proposal, she argues, would provide deeper affordability for projects in the LIHTC program by having higher earners “cross-subsidize” lower income renters.

In a 100-unit building, for example, 40 units could be reserved for renters at 60 percent of AMI, while another 40 units could be reserved for tenants making less – let’s say half for renters at 50 percent AMI and half for renters at 30 percent. The remaining 20 units would be held for renters at 80 percent AMI and help fund the lower income units. Rents in the building could range from $413 a month to $1,740 a month, compared to rents of $1,123 a month under the current requirements.

Compared to the current model, income averaging “would give you much more flexibility,” argued David Schwartz, a principal at Slate Property Group. “The more financing options we have will make it easier to do more affordable housing.”

“It could be a great thing,” Schwartz added.

Income averaging has also gained support in Washington in recent years. President Obama’s last five proposed budgets included income averaging among the administration’s proposed changes to the LIHTC program. The last three budgets estimated that the change would have an insignificant effect on revenue.

Democratic senators Chuck Schumer of New York and Maria Cantwell of Washington introduced a LIHTC reform bill last year that included a provision on income averaging. Fee anticipates that the bill will be reintroduced this session.

But why not just change the formula that determines AMI as some suggest? Just a few weeks ago, Democratic state Sen. Michael Gianaris and Assemblymember Brian Barnwell introduced legislation that would change the AMI formula for future developments, possibly impacting projects receiving 421a.

Changing AMI calculations, though, may negatively impact affordable housing development by making projects less financially viable, according to one HUD spokesperson.

“It’s kind of a false solution to a real problem,” added Seth Pinsky, an executive vice president at RXR Realty. To increase affordability, “you don’t need to change the calculation of AMI,” he argued. Instead, projects could be required to make units affordable to renters at a lower percentage of the same AMI. Pinsky has also argued for means testing, which involves determining whether a person is financially eligible to receive government assistance.

In the end, changing the formula to lower AMI would not change the fundamental costs of building affordable housing, according to Schwartz. With decreased rents, projects would require larger public subsidies because they may not be able to support as much debt. The result, Schwartz says, would mean fewer units of affordable housing.

Because federal law stipulates how the government determines AMI in the city, changing its calculations would require an act of Congress, said one HUD official familiar with the process. It’s not clear whether Congress will take up the issue.

“Affordable housing is tricky,” Pinsky said. “We spend enormous sums of money on it, and much of it is directed at the wrong population.”