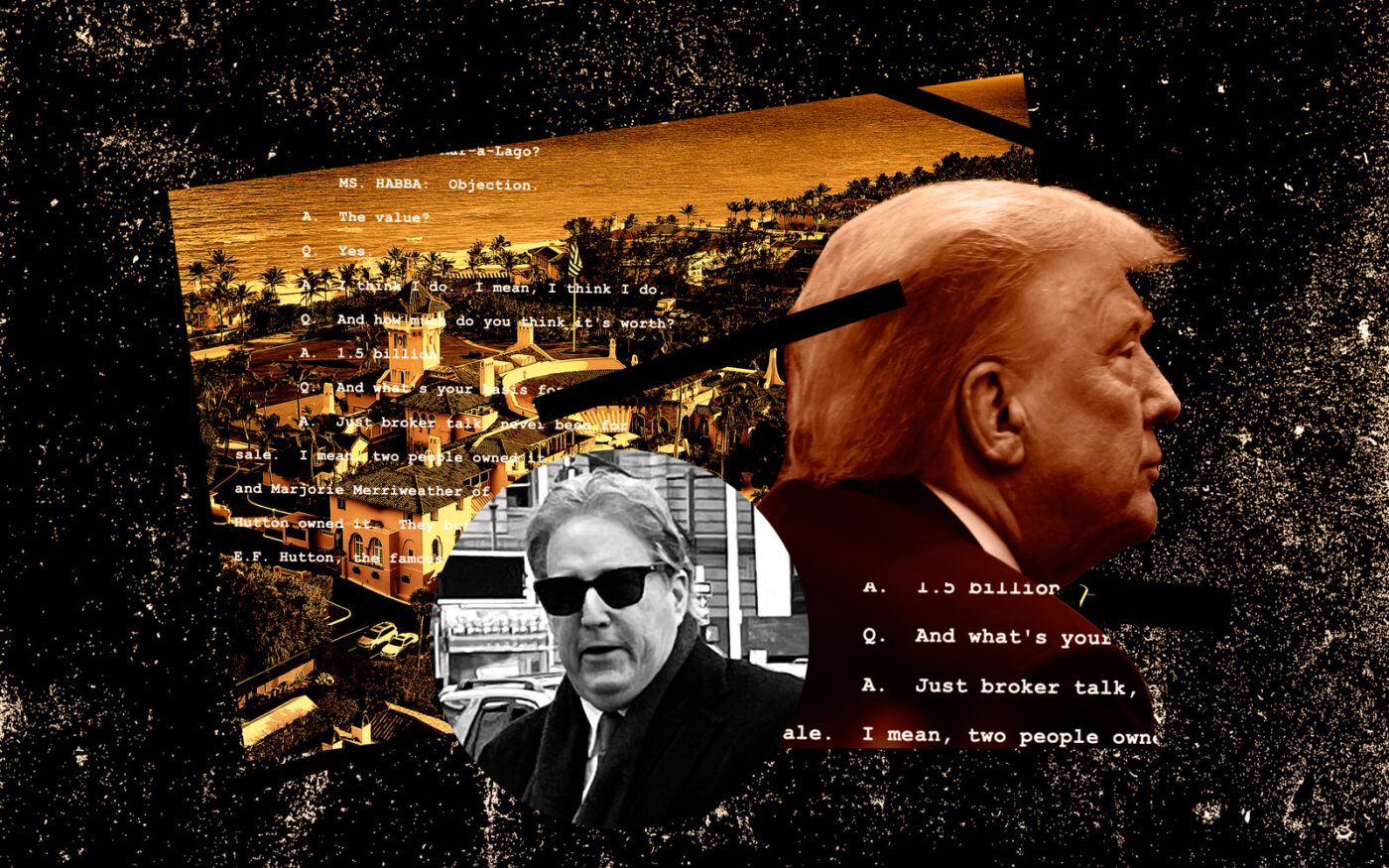

When Donald Trump needed an expert to value Mar-a-Lago, a key piece in his New York civil fraud case, he turned to a familiar face: Lawrence Moens.

Moens has been the go-to residential broker in Palm Beach for decades. He’s brokered $11 billion in sales, representing Ken Griffin, Larry Ellison, Steve Wynn and legions of buyers hidden behind LLCs. In 2008, Moens brokered a record $95 million sale of Trump’s oceanfront estate to a Russian fertilizer billionaire.

Trump is relying on other big-time real estate players, including Steven Witkoff, to provide expert opinions on valuations for his portfolio in the New York case.

But Moens, whom Trump paid $950 an hour for his efforts, is different. A man who deeply values his secrecy and built part of his business on it, Moens has been thrust into the highest-profile legal battle in the U.S.

New York Attorney General Letitia James alleges Trump, his sons Eric and Don Jr. and the Trump Organization provided banks with false financial statements. In September, a New York judge ruled that the company inflated valuations, leading the judge to rule to revoke its business licenses. On Friday afternoon, an appeals court judge halted the revoking of Trump’s business licenses. The future of the firm’s lucrative real estate assets is unclear.

Moens plays a unique role in Palm Beach, where social class and discretion matter most. He’s a real estate matchmaker to the 1 percent. Unlike most real estate brokers, Moens shuns publicity. No photos of him exist online.

His website is similarly bare, with only a few photos of listings and his motto: “See Palm Beach… Live Palm Beach — Lawrence Moens.” When The Real Deal asked competitors to comment on Moens for a profile last year, nearly all refused.

Moens declined to comment for this story. A representative for Trump did not return a request for comment.

Vast discrepancy

Mar-a-Lago is among the most scrutinized properties in Trump’s case. The former estate of socialite and businesswoman Majorie Merriweather Post is worth $1.5 billion, Trump said in April. He based the valuation on “broker talk,” according to his deposition. Meanwhile, in financial statements, Trump valued the property as much as $612 million.

But James alleges Trump grossly overvalued it, defrauding lenders who extended loans secured by the luxury resort.

The attorney general’s expert estimated Mar-a-Lago’s maximum value was $111 million in 2021. The expert, Larry Hirsh, cited a 2002 deed restriction signed by Trump, which stated that Mar-a-Lago intended to “forever extinguish their right to develop or use the property for any purpose other than club use.”

To refute that valuation, Trump tapped Moens, who valued Mar-a-Lago somewhere between $750 million and $1 billion, according to his deposition.

To put it into perspective, a $1 billion sale would be the biggest in Florida’s history. In 2019, Boca Raton Resort & Spa sold for $875 million, a record for commercial sales. Last year, a Manalapan estate sold for $173 million. And since the pandemic, luxury home prices in Palm Beach have skyrocketed; even a teardown traded for $155 million.

But Moens is thinking bigger for Mar-a-Lago.

“There’s nothing quite like it, though there are a handful of places in the world. I guess the Taj Mahal in India,” said Moens. “It’s magnificent. One of the greatest structures there is on the planet Earth.”

Moens said there would only be a handful of potential buyers in the world.

“I could dream up anyone from Elon Musk to Bill Gates and everyone in between. Kings, emperors, heads of state. But with net worths in the multiple of billions,” said Moens.

Moens’ valuation does not rely on the property’s current or potential use — a sticking point for the attorney general and the judge on the case, Arthur Engoron.

“As a personal residence, it’s not impractical to think that they can afford to buy it, use it for their own family use,” Moens said of his multi-billionaire clients. “They could do that because I deal with such great wealth, it’s on a magnitude that’s still unbelievable to me, guys with tens of billions or hundreds of billions of dollars.”

But because Mar-a-Lago cannot be anything but a private club, given the deed restriction, Engoron ruled that the Trump Organization could not ignore that in its valuations.

“Assets values that disregard legal restrictions are by definition materially false and misleading,” he wrote.

The attorney general made a motion to strike Moens’ testimony, arguing that he is not an appraiser.

“Mr. Moens’ estimates are based on almost no disclosed data and no verifiable methodology whatsoever,” her motion said. Instead, they are based on “speculation and “fantasy.”

The judge last month deemed Moens’ affidavit “unpersuasive and certainly insufficient to rebut” the attorney general’s case.

In his deposition, however, Moens defended his valuation, citing his experience and knowledge of the market.

“My numbers are right. My numbers are depictive of what the value of that property is worth much more so than theirs,” said Moens, referring to Trump’s. “They’re off by a mile. They’re not even close. They’re too low. That is my opinion.”

Read more