A controversial megaproject planned outside Miami-Dade County’s Urban Development Boundary faces new opposition.

In the latest move, a resident is asking the state to review commissioners’ recent approval of the UDB expansion. The vote allows for the 5.9 million-square-foot South Dade Logistics and Technology District industrial complex to be constructed in southeast Miami-Dade.

Nita Lewis, who owns a home near the development site, is asking for a state administrative judge to hold a hearing — and ultimately nix — the approval, saying it does not comply with state law aimed at discouraging development on exactly the type of site on which South Dade Logistics is planned.

Lewis filed her petition to the Florida Division of Administrative Hearings, which hears disputes between residents and governmental agencies, against Miami-Dade. The South Dade Logistics developers, Stephen Blumenthal and Jose Hevia, are not named in the filing.

The 39-page petition echoes the points environmental groups opposed to South Dade Logistics have made throughout the year, decrying future dangers of building out the development site.

“To ensure that Miami-Dade can prosper now and in the future, our community must take on its greatest challenges, such as sea level rise, flooding, and pollution of Biscayne Bay,” Lewis said in an emailed statement. “I am concerned that this development will endanger the homes

in the area, including my own home.”

The UDB is a way to restrict suburban sprawl west toward the Everglades and east toward Biscayne Bay, and aims to preserve farmland and wetlands that also are a buffer from coastal flooding.

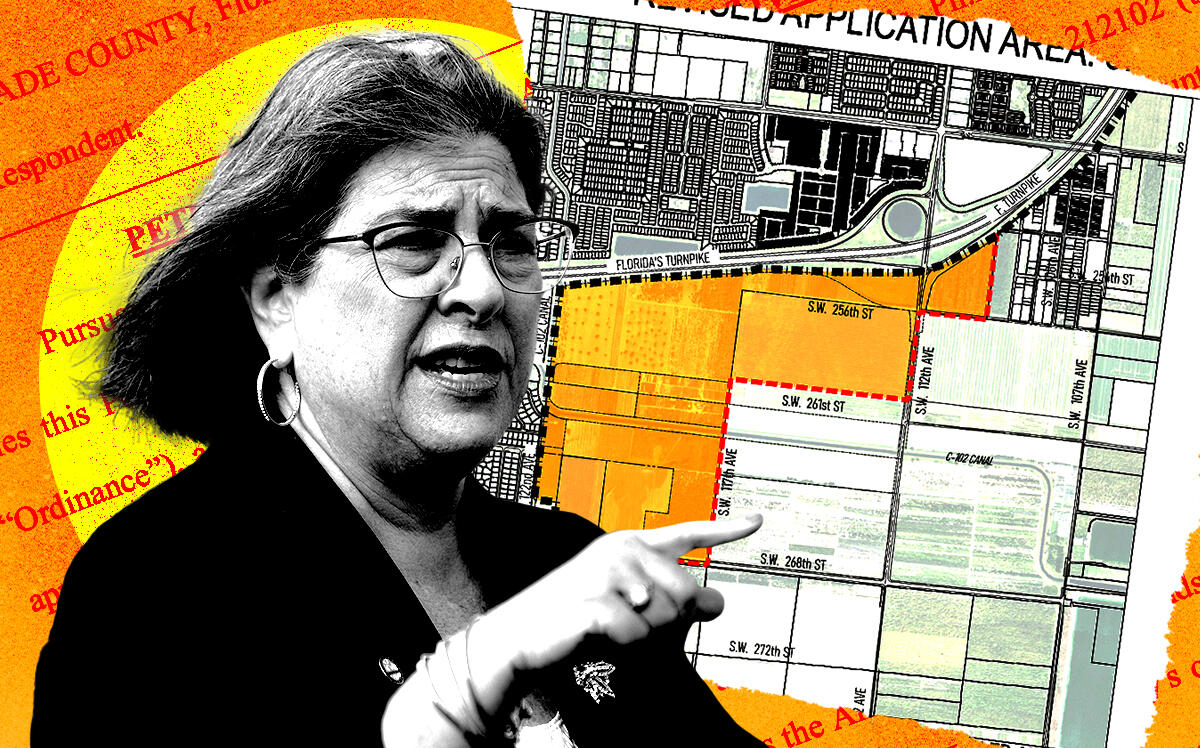

Blumenthal, principal of Coral Gables-based Coral Rock Development, and Hevia, president of Miami-based Aligned Real Estate Holdings, want to build South Dade Logistics across 378 acres on the southeast corner of the Florida Turnpike and Southwest 122nd Avenue. The project also will include offices and retail.

The land is two miles from Biscayne National Park and close to the C-102 canal, according to the petition. Building out the site could hinder plans to buffer the county from sea-level rise, as well as restoration of the Everglades and Biscayne Bay, including a combined rehabilitation initiative called the Biscayne Bay and Southeastern Everglades Restoration, the petition states.

Lewis cites numerous state departments’ letters from last year saying that the development site includes land that is being studied for use in the Biscayne Bay and Southeastern Everglades Restoration project. The land could be used to store flows from the C-102 canal, allowing for more controlled discharges into Biscayne Bay that are held back during the wet season and released in the dry season, the petition says.

Also, the project is in a Coastal High Hazard Area, areas vulnerable to flooding from storms. Although the development essentially would fill and thereby raise the land, Lewis argues in her petition that this does not render the site as not in a Coastal High Hazard Area.

In fact, state law says that local governments should limit their spending to subsidize development in these areas, according to Lewis’ petition.

Miami-Dade Mayor Daniella Levine Cava, who opposed the UDB expansion, has cautioned commissioners that the project would necessitate big spending to expand infrastructure to service the development.

Commissioners’ approval to move the UDB also is contrary to the county’s own comprehensive development master plan, or a blueprint for growth and development. For one, the project poses unique challenges to expanding roads to the area. Also, the development would degrade water quality, as the developers’ stormwater management plan is flawed, Lewis argues in her petition.

The filing also again makes opponents’ argument that there is no demonstrated need to expand the UDB for this project because plenty of industrial sites exist within the boundary. And the comprehensive plan also calls for the preservation of farmland, which currency exists on portions of the development site. The Hold The Line Coalition, which fights UDB expansions, has argued that Miami-Dade farms are expected to play a pivotal role in future agricultural needs.

Blumenthal and Hevia declined to comment through a spokesperson. But the pair has long maintained that their project not only wouldn’t degrade the environment but actually will be beneficial. It would still allow for discharges into the bay but without the polluted runoff from the farms, the duo has said.

Plus, commissioners in support of the project have said that the land is so low-lying that it has been rendered nearly useless for farming. Keeping it outside the UDB prevents these farmers from selling their properties at a higher price, they say.

It took Blumenthal and Hevia five tries this year to score approval, which they did on Nov. 1 when they obtained the needed threshold of eight commissioners to support their project.

Throughout the process, the developers tweaked their project multiple times — and gained more commissioners on their side, in return.

In one of the biggest changes, they dropped South Dade Logistics’ original size by roughly half. In another move, they vowed to donate 622 acres of environmentally sensitive land elsewhere to a county preservation program.

Levine Cava vetoed the approval on Nov. 10 but commissioners overrode her veto five days later.

The last time Miami-Dade moved its UDB was in 2013 to include 521 acres west of Doral.

Read more