UPDATED, Aug. 7, 11:40 a.m.: When the Miami City Commission rejected a proposal last year to upzone east Little Havana, it did so in the name of protecting the area from overdevelopment, commissioners said.

Now, developers have adapted, and mid-size projects are on the rise.

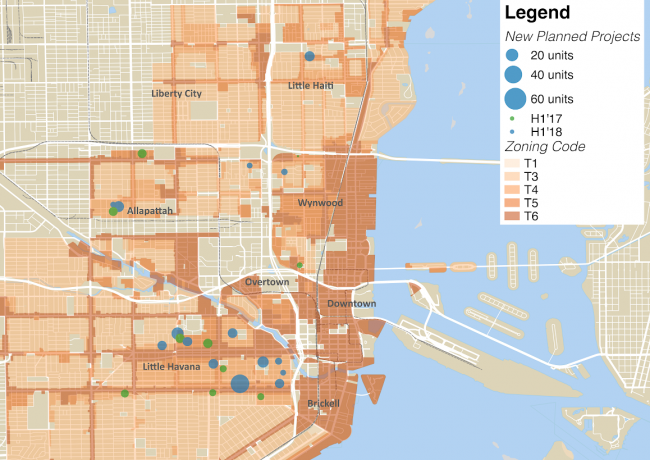

In the first half of 2018, the number of planned rental units in medium-density zones rose nearly 40 percent to 196 over the same period last year, when planned units totaled 142, according to The Real Deal‘s analysis of new permit applications filed with the Miami Department of Buildings.

Almost all of that growth was driven by projects in Little Havana, where new filings jumped from 48 units in the first half of 2017 to 155 in 2018.

Most of the neighborhood is zoned for medium-density development – either T4 or T5 – with high-density T6 corridors crossing it in a grid along West Flagler, Northwest Seventh Street and Northwest 27th Avenue.

That means that development is capped at five stories tall and 65 residential units per acre, the maximum number of units allowed in a T5 zone.

But rather than constrict development, the zoning seems to have enticed builders to work with what they have, partly because demand is too strong to pass up, according to Jose Boschetti Jr., who’s awaiting his permit to build 24 studio apartments at 726 Northwest Third Street.

Boschetti Jr., whose father, Jose Boschetti, leads the Miami-based BF Group, is building micro units – about 400 square feet each – with rents starting at $1,250 per month.

“I don’t want to say ‘affordable units,’ because these aren’t affordable, but the rents are going to be low because they’re small,” he said. He’s hoping to attract renters priced out of downtown Miami and Brickell. “The zoning code allows us to do what we’re doing,” he added.

Metronomic, a development firm led by Ricky Trinidad, has kept up its pace of activity in the neighborhood. Trinidad, an early investor who has sought to build a branded line of “TriniSuites” targeting college students, filed plans for 53 new units in 2018, bringing his firm’s total for the area to 202 units under development.

Many of those projects are funded by non-bank lenders, Trinidad said, like Spectrum Mortgage Group or Fuse Funding, both South Florida firms. Their interest rates can be more than double those of a conventional bank — as much as 11 percent — but the lack of red tape and the freedom to build quickly make up for the cost.

Trinidad said that those lenders will sometimes waive the appraisal process after the developer submits their prospectus. “We just send them the stuff, and we close in 30 days. They like the fact that we’re in Little Havana,” he said, adding that the interest payments are negligible once a project is completed and refinanced, or sold.

And to expand quickly, it helps to avoid the politics of zoning altogether, Trinidad added. He doesn’t try to spot-zone a development site for denser use. “We build by-right,” he said. “You don’t need favors.”

Still, zoning isn’t everything, and other neighborhoods with a similar composition have failed to attract the same degree of investment.

In Little Haiti, for example, only one mid-rise project filed for a building permit in 2018, despite its large T4 and T5 zones around Northeast 54th Street. No projects filed for permits the previous year.

Alex Gomez, a general contractor who lives and works in the neighborhood, claims that Little Haiti’s high number of single-family homes can be a bottleneck for development.

With the time it takes to get approval for a complete teardown, he said, investors looking for a medium-sized project with a two-year turnaround may prefer to look elsewhere. He’s seen developers, many from Latin America and Europe, walk away.

“It’s an obstacle,” he said. “They go somewhere else.”