Overlooking a small lake in a quiet area of Mid Beach, The Ritz-Carlton Residences, Miami Beach was pegged as an upscale European oasis in South Florida.

Ophir Sternberg, a native of Israel who moved to Miami in 2009, tapped Italian architect Piero Lissoni to design the project, where homes would range in price from $2 million to $40 million. It was Lissoni’s first U.S. venture, and Sternberg hoped to use him to deliver product that was “more European” and “more Italian” than anything Miami had seen before.

But when Sternberg’s Lionheart Capital needed financing to finish the project in the summer of 2015, he looked not to the old world, but toward an obscure regional bank smack in the middle of Arkansas.

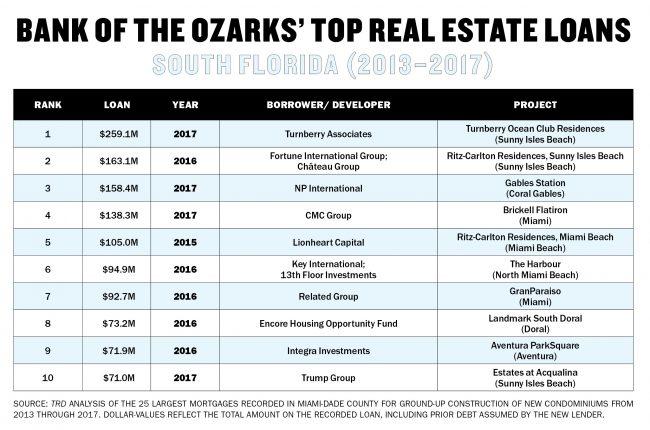

Lionheart secured a $105 million construction loan from a lender called Bank of the Ozarks, which included assuming $10 million in existing construction financing. It was one of the first major construction loans in South Florida by the bank. By the following year, however, press releases and news articles made clear that Ozarks, a name that people were more likely to associate with a popular TV show, was shaping up to be one of the area’s biggest construction lenders.

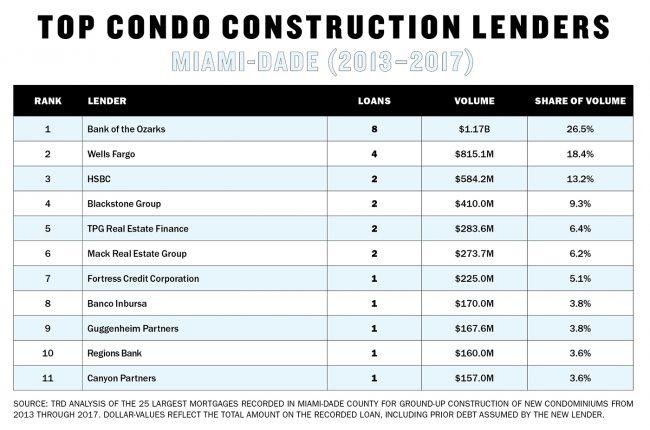

During a period when banks across Florida were hesitant about lending on large construction projects, Ozarks was on a tear: With just over $22 billion in assets on its books, it provided more than $1.2 billion in construction loans in the Miami metropolitan area from 2013 through 2017, according to the company’s annual reports. In Miami-Dade alone, the bank was the largest condo construction lender for the county’s biggest projects, responsible for 26.5 percent of the total dollar volume of loans issued to the 25 biggest projects during the last five years, an analysis by The Real Deal shows. Compare that to Wells Fargo, the next biggest condo lender in Miami-Dade, which was responsible for 18.4 percent of the dollar volume of loans to those projects. Wells Fargo is the third-largest bank in the U.S., with nearly $2 trillion in total assets – that’s nearly 100 times the size of Ozarks.

Ozarks’ deals include a $259 million construction loan for Turnberry Associates’ 54-story oceanfront luxury condo tower in Sunny Isles Beach and a $138.3 million loan for CMC Group’s Brickell Flatiron. The 10 biggest construction projects it’s backing in Miami-Dade are slated to bring 3,289 new residential units to market, a mix of condos, rentals, and senior housing.

“We are proud to be contributing to the economic vitality of South Florida with our loans to many of the region’s marquee properties,” a spokesperson for Ozarks said.

But while some believe that Ozarks is a disciplined lender that’s merely filling a big void in lending activity, others question if it is overly exposed to one of the country’s most speculative real estate markets. Its critics draw comparisons to Corus Bank, a Chicago-based lender that aggressively financed condo construction in South Florida and was seized by regulators in 2009 after the condo market collapsed.

Like Corus, critics say, Ozarks could face challenges with maintaining its capital levels if there is an economic downturn, and point to the bank’s last annual report which shows that its concentration of construction loans is more than double its guidance. They also point to the bank’s high rates on deposits, its non-syndicated lending, as well as the sudden resignation of the bank’s chief lending officer as warning signs.

“There are some people out there that feel that this bank is almost like the Wizard of Oz – Dorothy thought that the Wizard could do everything,” said Kenneth Thomas, a Miami-based banking analyst. “All of (Bank of the Ozarks) numbers look amazing on paper, but it’s just a bank.”

Rendering of Ugo Colombo’s Brickell Flatiron. Bank of the Ozarks provided a $138.3 million construction loan for the project.

The South Beach diet

Founded more than 100 years ago in Jasper, Arkansas as a small community bank, Ozarks’ growth in South Florida and other large metropolitan areas stems directly from the Real Estate Specialities Group. George Gleason, a 64-year-old former attorney who leads the bank, has previously said that 2003, the year in which this group was formed, was the most important year in the bank’s history.

Based in Dallas, the group was led for most of its existence by Dan Thomas, a CPA and a former executive at a development group. Staffed by a team of attorneys and real estate professionals, it operates almost akin to a splinter group, responsible for the bank’s underwriting and overseeing the company’s debt on ground-up development projects. By the end of the first quarter of 2018, it accounted for more than $8.7 billion, or 64 percent, of the bank’s total non-purchase loan portfolio, according to an investor presentation.

The group started to attract interest in 2012, when it ventured into the New York market. Some banks, wary of regulatory concerns, had pulled back from financing ground-up projects, and Ozarks carved out a niche in originating medium-sized, non-recourse loans at attractive rates. (Non-recourse loans are generally riskier for lenders because in case of default, the lender can only go after the collateral.)

By the end of the second quarter of 2016, Ozarks had made $1.9 billion in real estate loans in New York City, with construction loans totaling $1 billion.

It then began to move into South Florida. In July 2016, the bank purchased Tampa-based C1 Financial, giving the institution about $1.6 billion in assets and 33 branches across the state. That year, Ozarks increased its construction-loan activity in South Florida to $312.2 million, up 214 percent from $99.2 million in 2015, according to its annual report.

“They are the lender of first resort to borrowers and also the lender of last resort,” said Thomas, the independent analyst, who noted that borrowers sometimes look to the bank when they can’t get financing from other places.

Ozarks’ borrowers and brokers who’ve worked with it, however, describe it as a disciplined lender that works with developers who’ve shown a strong track record.

“In general, they are wonderful lenders,” said Charles Penan of Miami-based debt brokerage Aztec Group. “They’ve been able to diversify their locations and they have had discipline.”

Penan noted the bank has the ability to make very large loans and offer non-recourse financing, which is unusual in the development lending business today.

“They are not the cheapest bank in town, but they are offering non-recourse and a lot of borrowers are offering to pay for non-recourse,” he said.

In a recent investor presentation, Ozarks also said that it reduces its risk because it “is always the senior secured lender” meaning that if a project did fail, it would be the first one to get repaid.

Michael Rose, an analyst with Raymond James who has a “strong buy” rating on Ozarks, believes its approach is conservative, in part, because its deals are structured with about 50 percent equity in the project from the developer or sponsor.

After the equity portion, there is generally subordinated and mezzanine debt in the project, which means that Bank of the Ozarks is typically only financing 13 to 35 percent of the project value, he said.

“The reason they don’t lose money is because there is so much equity in deals,” said Rose. “It’s really hard to see how they would lose money, they are always the senior secured lender.”

Rendering of Turnberry Ocean Club Residences. Bank of the Ozarks provided a $259 million construction loan for the project.

Making it rain in the Sunshine State

In 2017, Ozarks issued $1.15 billion in real estate loans in South Florida out of which about $746.5 million was construction financing, according to its annual report. Notable projects include Miami Worldcenter and Turnberry’s Sunny Isles Beach project in 2017, and the Magic City Innovation District in 2018.

For comparison’s sake, Miami Lakes-based BankUnited, which is South Florida’s largest bank by assets ($30 billion-plus), only had $165 million in construction loans on its balance sheet in the second quarter of 2017. Ozarks’ one loan to Turnberry of $259 million was about 1.5 times the size of BankUnited’s total construction-loan portfolio.

“With banking in particular, the locals understand the local market better than the out-of-towners,” said Peter Zalewski, a principal with the Miami real estate consultancy Condo Vultures. “You got to scratch your head and say, ‘what do the out of towners know that the locals don’t know?’”

Frank Gonzalez, who oversees the audit department at the accounting and advisory firm MBAF, said tri-county banks are generally not doing much construction financing.

“The regulators are focusing on that (construction lending) especially in South Florida,” Gonzalez said. “From our end as a financial auditor, it’s one of the key areas of focus, when we see it (construction lending on bank’s balance sheets) we kind of cringe.”

Ozarks’ mentions in its most recent annual report that its commercial real estate loan portfolio “may subject the company to additional regulatory scrutiny.” The bank also reported that it has more than doubled its guidance, set in part by the FDIC, for its concentration of construction lending relative to its capital levels at 209 percent.

Gleason, who purchased a controlling interest in Ozarks when he was 25, is a major backer of Republican candidates who support repealing provisions of the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. According to the National Institute of Money in Politics, Gleason has donated more than $89,000 over the past 14 years to Republican candidates, while his wife, Linda Gleason, gave another $82,000.

Going the distance

Adding to the concerns over the bank is the abrupt departure last July of Thomas, the longtime head of the Real Estate Strategies Group.

Thomas, who rarely spoke in earnings calls or gave media interviews, served as the chief lending officer at Ozarks from August 2012 to July 2017, and was widely seen as the catalyst for the bank’s massive real estate push. When news of his departure hit, the company’s stock dropped 12 percent.

“You are there for over 14 years, it was a great run. I moved to a different company and they’ve moved on to new management,” Thomas, who is now president of Dallas-based LandPlan Development Corp., said in an interview with TRD. He noted that he no longer owns any of Ozarks’ stock.

A spokesperson for the bank said that the real estate group’s “focus is on building a loan portfolio with the lowest credit and interest rate risks utilizing discipline and expertise.”

Some, however, have questioned whether its strategy is sustainable.

Carson Block, a well-known short seller who made a name for himself exposing fraud in Chinese companies, warned in a presentation in 2016 that Ozarks is overexposed to commercial real estate and construction lending in particular. He said the bank had too many unfunded balance sheet commitments, meaning it will need to continue to make acquisitions in order to fund its lending.

The bank has acquired 15 banks since 2010 and Gleason indicated it will continue on this trajectory.

“We expect we will make additional acquisitions, many of them in the future,” he said in the company’s January earnings call. “We’ve got a great organic model, and as we’ve always said, acquisitions are icing on the cake in addition to that organic growth model.”

And in a few months, the lender is set for a big change: Bank of the Ozarks will drop the reference to its origins and rebrand as Bank OZK.

“It frees us from the limitations of a name tied to a specific geographic region, ” Gleason said in a statement at the time.

A name-change, however, will only add to the mystique of the lender perhaps most responsible for shaping Miami’s condo market today.

“Bank of the Ozarks,” said Zalewski, “Is the most marketed bank in South Florida that no one understands.”