R.I.P., Town Residential. Over the course of a few hours on April 19, when it told agents the end was at hand, Town went from a megafirm with flashy Manhattan offices to a cautionary tale.

The bold residential brokerage, known for its over-the-top holiday bashes and agent benefits, burst onto the scene in 2010 and quickly ballooned to 600 agents and 10 offices.

The firm, which was founded by industry veteran Andrew Heiberger — who had sold his first brokerage, Citi Habitats, in the early aughts for roughly $50 million — quickly took a spot next to the industry’s most established players.

But that was before a public and bitter dispute between Heiberger and his financial backer, Joseph Sitt. After the two buried the hatchet, Town seemed to be on relatively stable ground. But then last summer rumors started to swirl that the cash-strapped company was struggling to pay its bills.

What followed stunned the industry. In a four-day span last month — after getting hit with two lawsuits over unpaid rent — the company made the bombshell announcement that it would close its core resale and leasing divisions.

Town’s undoing has the ingredients of a Lifetime drama: the money, the lawsuits, the larger-than-life personalities.

Andrew Heiberger announced last month that he was shuttering Town’s resale and leasing divisions, citing a fierce climate that made it impossible “to make sustained profit.” (Photo by Studio Scrivo)

But the firm’s staggering collapse speaks to a much bigger existential issue for the industry. In the age of discount firms, star agents, open data and huge sums of venture capital, traditional brokerages are getting financially assaulted from all sides.

Even before Town’s downfall, some were characterizing traditional residential firms as a dying breed and predicting that they’d soon be obsolete.

Those skeptics point to the paper-thin margins as well as the rapid changes in technology and consumer behavior.

Two days after shuttering Town, Heiberger said as much, noting that the financial pressures left him no choice but to close the firm, which claims it sold $13.25 billion during its eight-year run.

“Due to extremely high commission costs and a fierce recruiting climate it was just not possible to make sustained profit,” he wrote on a LinkedIn post.

While some have noted that Town also spent lavishly, New York’s entire residential brokerage business is grappling with all the same outside forces — even as rival firms scramble to scoop up Town’s remains.

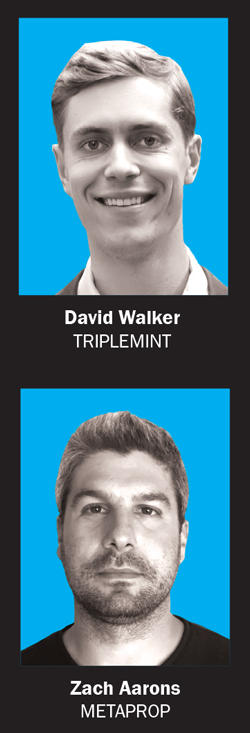

“There is as much unrest in residential brokerage around the country as there has been in my 31 years in the business,” said Steve Murray, founder of real estate data firm Real Trends, who added that companies like Redfin, Zillow and Compass have fueled a tech arms race and taken competition to a new level. “A multifront war is how the incumbents see it.”

According to Murray, the assault is eating into gross margins, the lifeblood of traditional brokerage firms.

Even the heads of some top Manhattan firms have acknowledged the precariousness of the business.

“It’s very hard for a company to succeed today because of the pressure on margins,” said Hall Willkie, co-president of Brown Harris Stevens.

In addition to commissions, his firm is spending heavily on IT, economists, market reports, online advertising and glossy publications. “Ten years ago, we thought we’d get rid of offices; instead, you have to have fancy offices,” Willkie said. “The agents demand it; the customers demand it. Everything has to be top-drawer.”

Despite those efforts, many startups argue that the brokerage Goliaths have not evolved enough.

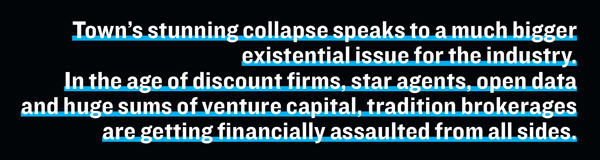

David Walker, CEO of Triplemint — a venture-backed New York City firm that launched in 2013 and uses data to predict when sellers are likely to list their properties — said consumers are “not okay with the traditional process.”

“They say, ‘Where is the increased value? I use apps to move around the city. I can get a mortgage online in three clicks’,” said Walker, whose firm has 70 agents but doesn’t disclose sales figures.

That argument has resonated on Wall Street, where giants like Realogy — the parent company of the Corcoran Group, Sotheby’s International Realty and suburban firm Coldwell Banker — and Douglas Elliman, which is owned by publicly traded Vector Group, have struggled with profitability.

“We are not bulls on the long-term importance of brands in residential real estate,” Anthony Paolone, an analyst at JPMorgan who covers Realogy, wrote in March. Although agents will continue to play an important role in complex transactions, he added, brokerage firms’ earnings are in flux.

“I always say to people, it’s not a great business. If my name wasn’t on the door and you said, ‘Would you go into the business today?’ I don’t think I would,” said Jed Garfield of the Manhattan-based firm Leslie J. Garfield & Company, which specializes in townhouses.

“The notion that a real estate brokerage business makes money — I don’t know anyone who owns or runs a brokerage business, whether it’s huge or small, that’s like, ‘Oh yeah, I’m crushing it.’”

The tech and data arms race

In many ways, the seismic shift in the brokerage business can be summed up in one word: data.

Just over a decade ago, the brokerage world was shaken to its core when StreetEasy launched and suddenly gave the public access to listings information that had forever been tightly held by brokerages. That shifted the balance of power from agents to consumers.

It also left brokers grappling with how to add value for clients — beyond what they could easily find on their laptops.

That push-and-pull is still going on — and firms are now racing to invest in data and tech at a breakneck pace, putting more pressure on their bottom lines.

Rob Lehman, chief revenue officer at Compass, said the firm is creating tech that supports agents as they consolidate into teams that run like small businesses.

“The role of the traditional brokerage is actually going to go away entirely,” he said. “The role of the brokerage in the future is to supercharge the business of these incredibly large and complex [teams].”

Compass, founded by Robert Reffkin and Ori Allon, has created a single platform with tools for agents to share listings, create show sheets, analyze comps and manage deal flow.

But the firm has a leg up because it’s building the infrastructure of a tech-focused firm from scratch — rather than wedging upgrades into an existing infrastructure. And its deep-pocketed investors have given it the equivalent of a blank check.

On the data and tech fronts, traditional firms are playing catch-up with mixed results. And it’s coming at a steep cost at a time when profits from residential sales are waning.

“Now the game is, ‘Does your business produce enough cash flow to invest in what you need?’” said Real Trends’ Murray. “A normal person would say, ‘No.’ The key is, how much tech do you really need?”

Nobody knows for sure, but traditional firms aren’t taking chances. Instead, they’re spending tens — and hundreds — of millions of dollars on tech.

Last year, Keller Williams created a $1 billion tech fund, and it recently introduced a voice assistant called Kelle, which follows commands like “Kelle, call my buyer.”

Realogy spends $200 million a year on tech, according to CEO Ryan Schneider, who has outlined an ambitious path to develop new products.

According to Elliman Chairman Howard Lorber, brokerages that don’t invest in tech are toast.

“Do I lose sleep that I’ll be put out of business by a real estate tech company? No, I don’t,” Lorber said. “Technology is a tool, and if you’re a real estate company not investing in both the agent and technology, you probably won’t make it.”

Elliman is, however, being more strategic about its tech expenditures: Last fall, it scrapped its in-house listing system and struck a deal with StreetEasy to build it a custom system. And it’s getting ready to launch an “app store” this spring where agents can customize a dashboard of apps from roughly 20 vendors like Compit, BoardPackager and Edge.

“Technology is expensive,” Lorber said, noting that some competitors are trying to excel in both tech and real estate. “I don’t know how realistic that is to make it work, or how you can even be that competitive on both of those areas at the same time.”

Dozens of real estate-focused tech startups are banking on Lorber’s theory that traditional firms are going to outsource their tech upgrades and pay handsomely to do so.

For example, the venture-backed startup Perchwell — which gives agents a single platform for managing listings, compiling research and collaborating with clients — has picked off major clients from rival RealPlus, including Sotheby’s, Stribling and CORE.

Brooklyn-based VirtualAPT — whose clients include agents at Elliman and Stribling — has a proprietary robot that does 360-degree digital property tours.

“There are a lot of firms that are really established that need to lean into the future,” said VirtualAPT’s founder, Bryan Colin. “These brokerages can either adopt new technology — and they can figure out what they need to keep their brokers happy — or they become dinosaurs.”

And if they do go the way of dinosaurs and become extinct, there are plenty of online platforms ready to fill the void.

Losing out to lead generation

New York agents woke up on March 1, 2017, to the industry’s version of a brave new world.

That was that day that Zillow went live with Premier Agent on StreetEasy, its New York site. The controversial program allows agents targeting buyers to advertise next to other brokers’ listings. Buyers seeking information about properties are automatically directed to the so-called Premier Agent — not the listing broker.

The city’s biggest firms acted fast, calling for a boycott of the portal, which they said was causing consumer confusion. The Real Estate Board of New York complained to the New York Department of State, arguing that Premier Agent may violate advertising laws.

But the industry’s real concern about Premier Agent was the threat it poses to the old guard, leaving established players vulnerable to a hierarchical shakeup.

Overnight, no-name agents were chasing multimillion-dollar deals, bringing buyers to listings held by the city’s top producers, who generally work for the biggest firms.

“It’s been a business changer as far as I’m concerned,” said Compass agent Ethan Leifer, who’s spending $2,000 a month on Premier Agent for the Upper East Side, where that gets him an average of nearly 40 leads a month.

Leifer, who’s been an agent for six years, said he generated $10 million in sales and contracts in 2018’s first quarter. At that pace, he thinks he will hit $1 million in gross commission income just from Premier Agent this year — double his total 2017 earnings.

Leifer alone can’t make a dent in the big firms’ earnings, but if multiplied, Premier Agents are in position to chip away at the incumbents’ bottom lines.

Agents like Leifer haven’t just wrung more business out of Premier Agent. Zillow has leveled the playing field for them by giving them access to once-untouchable clients and pricier deals than they’ve ever seen.

Kobi Lahav — an agent at Mdrn. Residential who has done a steady clip of $500,0000 deals — recently closed a $2.7 million all-cash transaction at 400 Fifth Avenue for a Chinese buyer whose 21-year-old son found him through Premier Agent.

“Where do you find a $3 million cash buyer unless you’re Fredrik Eklund?” Lahav said, referring to the Elliman agent and “Million Dollar Listing New York” co-star.

“In the past, if you wanted to get those clients you had to work at the Elliman or Stribling — the companies with a brand name,” he said.

With Premier Agent, Lahav has leveraged Zillow’s name: “That’s where the traditional brokerage is being disrupted.”

While larger firms scramble to catch up, Premier Agent has bolstered smaller and newer firms — think LG Fairmont, Triplemint and Elegran Real Estate — by giving them the chance to purchase leads.

LG Fairmont, which launched in 2010, closed $221 million worth of deals in 2017, the year StreetEasy launched Premier Agent, up from $151 million in 2016. To date, the company —which raised a $1 million seed round in 2015 — has sold $718.4 million in real estate and generated 112,171 clients over the internet.

While some major firms have stuck to the StreetEasy boycott, others — including Elliman, Corcoran and Halstead Property — did a 180 and embraced Premier Broker, a version of the program that lets them buy leads en masse. (Realogy took things a step further by striking a deal with Zillow around rentals.)

By November, about nine months after Premier Agent launched, agents were flocking to the program, which uses auction-based pricing to determine the cost of leads. The program’s popularity had jumped so much that the cost of a lead on the Upper West Side, to use one neighborhood example, had skyrocketed 174 percent, to $197 from $72.

And Zillow, which is laughing all the way to the bank, pulled in a record $1.08 billion in revenue in 2017 — up 27 percent year over year. Revenue from Premier Agent, which accounts for 71 percent of the company’s earnings, shot up 26 percent.

“We’re in growth mode,” CEO Spencer Rascoff said during Zillow’s latest earnings call, in early February. “The market opportunity in front of us remains massive.”

But some firms are still unwilling to foot the bill for Premier Agent, leaving it up to agents to use their own marketing dollars as they see fit.

Analyst John Campbell, of the Stephens investment bank, said brokers are rightfully wary of Zillow’s next move.

He characterized the Seattle-based listings giant as providing short-term gains for brokers, but said that engaging with the site could come back to haunt them.

On the one hand, the company is the “arms dealer and an outsourced technology shop” that can help brokers stay competitive today. But on the other, relying on Zillow’s leads “has to be a scary thing,” knowing that the portal could soon become a direct competitor.

Vying with venture capital

A decade ago, the idea of a $2.2 billion brokerage was laughable.

But today one of the residential industry’s most serious threats is Compass, which with its newly minted $2 billion-plus valuation has upended the brokerage landscape and stolen many of its rivals’ top agents.

While Town was the first new postrecession megafirm on the scene when it launched in 2010, Compass’ presence loomed even larger. Since launching in 2013, the startup has mushroomed to 3,400 agents nationwide. In 2017, the firm generated $370 million in revenue.

None of that growth would have been possible without venture cash.

The firm has raised $775 million to date, including $450 million from SoftBank.

And the influx of venture capital into the brokerage world extends beyond just that one company. Investors have poured money into Seattle-based Redfin and the U.K.-based startup Purplebricks, for example. And they’re throwing their weight behind companies that manage listings, like Nestio (which has raised $11.9 million) as well as rental and co-living startups like Common ($63.5 million) and Roomi ($17 million). Those firms are helping landlords and tenants do deals and shaking up the way brokerages did business.

LG Fairmont’s CEO, Aaron Graf, said these startups have targeted a “falling commission environment” that traditional firms are now operating in.

“If you really drill down, the disruption in the industry is around making operations more efficient,” he said. “That’s what the VC and tech money is attacking now.”

Compass has wooed investors and brokers, for example, by promising agents that its technology will boost their productivity.

“Our view is that the real estate agent should be doing 10 to 20 times the volume than they currently do,” said Compass’ Lehman.

Lehman said the average agent nationwide nets $330,000 in gross commission income a year. At Compass, he claimed, agents grow their business by an average of 25 percent in year one.

But skeptics said Compass is burning through cash in order to hire agents and open offices at an unprecedented rate.

“It’s easy to spend other people’s money, but when will they get the return?” said Elliman President Scott Durkin. “I know how hard it is to make money in real estate. I’m not sure where they’re finding that pot of gold.”

Garfield said that based on his margins, he’d “be well out of business doing what [Compass is] doing, and would have been several years ago.”

But investors have not been deterred from moving into the real estate space.

Overall, global venture capital investment in real estate tech skyrocketed to $12.6 billion in 2017 — up from $4.2 billion in 2016. That jump was bolstered by SoftBank’s $4.4 billion investment in WeWork and $450 million infusion in Compass, according to research company RE:Tech.

“It’s an easy space to invest in because it’s been a tech laggard,” said Jenny Lefcourt, an investor at San Francisco-based Freestyle Capital, which has backed Nestio as well as San Diego-based startup Agentology, which helps agents respond quickly to leads.

“You can look at other industries and say, ‘Of course it’s going to happen here.’ So to some extent, there’s a playbook for what’s happening,” said Lefcourt.

But to critics who fear tech will replace agents, Lefcourt said she’s on the hunt for companies like Agentology that give agents a competitive advantage.

Agents packing up and leaving Town’s Irving Place office after the brokerage announced that it was shuttering its core business (Photo by Ben Heitmann)

“In the old days, [agents’] value was the information that is now accessible to all,” she said. “Now consumers late at night are going on their computers, finding places they’re interested in and wanting someone to immediately respond.”

But investors aren’t just playing for sport, said Lorber. “At some point you have to make money,” he said.

Star brokers get the brand recognition

In the age of superbrokers, there’s no better example than Ryan Serhant — reality star, social media personality and agent at Nest Seekers International.

Serhant, a co-star on “Million Dollar Listing New York,” accounted for 57 percent of Nest Seekers’ listings, according to a 2015 analysis by TRD. That’s clearly good for Serhant, but what about Nest Seekers?

Top-producing agents who get high splits — often over 80 percent — can be loss leaders for a company, sources say.

“They think it attracts business by having those big brokers, even though they’re losing money on them,” said BHS’ Willkie.

Another brokerage chief put it even more bluntly: “Ryan Serhant is Nest Seekers, simple as that. What would they be if he left?”

While Serhant may be an extreme example, the star agent phenomenon has only gained momentum in recent years. Emily Beare, for example, accounted for 30 percent of CORE’s listings, according to TRD’s 2015 analysis, while Serena Boardman controlled 27 percent of listings at Sotheby’s.

But that newfound power — which has some agents re-evaluating their allegiances — is leaving firms vulnerable.

“A lot of star brokers are going to say, ‘Fuck this, I’m the star of my own firm. My office is on my iPhone X,’” said Zach Aarons, co-founder of MetaProp, a New York-based tech accelerator.

Against that backdrop, the relationship between brokerages and agents is growing more complicated — mainly because top producers have personal brands and books of business can be both an asset and liability to the firm. On the plus side, those star agents generate serious business and publicity. But on the downside, they not only have high splits, but they also yield enormous leverage over management.

The city’s largest firms have historically steered away from relying on any one agent or team. And in many ways, they’ve hedged against it.

Elliman, which brokered $5.23 billion in closed deals last year, limits teams to 10 agents. “In a small company, you’re waiting … for those big producers to leave,” said Durkin. “When they leave, the company suffers. It’s a very dangerous sort of existence.”

Unlike Elliman, Nest Seekers has given Serhant the leeway to build a 60-person team with offices in Manhattan and Brooklyn. “It enables me to run a company within a company,” Serhant said last year.

Although Nest Seekers has offices worldwide, it’s hard to dispute that Serhant has the stronger brand. On social media, he has 707,000 Instagram followers compared to Nest Seekers’ roughly 85,000. (Eklund, meanwhile, has 1.1 million followers compared to Elliman’s 94,100 followers.)

Eddie Shapiro, CEO of Nest Seekers, conceded that Serhant has an incredible “megaphone.” But he disputed the notion that the company relies too heavily on one person or team.

“There’s always this perception that the star brokers do all the business in the firm,” Shapiro said. “It takes a village to raise a child. There’s a lot of extremely talented people in that group.”

Shaun Osher, who founded CORE in 2005, said that although it has megaproducers, it doesn’t rely on top agents alone. Instead, it requires its agents to meet sales benchmarks. “We expect our agents to perform,” he said. “We’re small, so every agent has an impact.”

He said agents need their own identity and brand to attract clients.

Few agents successfully strike out on their own, Willkie pointed out, noting that the combination of the agent and company brands is key. He cited BHS’ John Burger, who dominates the uber-luxury co-op universe, as a case in point.

“John Burger has a brand and the company has a brand,” he said. “I don’t want the John Burger Group in my apartment. I want John Burger at Brown Harris Stevens.”

But even firms that publicly say it’s dangerous to rely on a single rainmaker are struggling with brand identity at a time when agents see the value of self-promotion.

Over the past year, top firms like BHS, Elliman, Corcoran and Halstead have shelled out millions of dollars on marketing and rebranding campaigns.

Halstead and BHS, which share Terra Holdings as a parent company, both hired the design consultant Pentagram, which has done campaigns for companies like American Express and Ferrari, to completely overhaul their logos and taglines.

“If we don’t have a strong brand, what are we?” asked Christina Lowris Panos, chief marketing officer at Corcoran, which “refreshed” its logo in February.

But as part of the rebranding, Corcoran also created customizable stamps that allow agents to put their names on Corcoran-branded marketing materials. Panos said that decision reflects Corcoran’s acknowledgment that agents have their own customers and run their own businesses.

RE:Tech founder Ashkan Zandieh said traditional firms are trying to keep up with Compass, which is operating on another level. “Compass has said, ‘We’re going to brand ourselves better and differently than previous companies have done because they’re flat-out stale,’” he said.

Discount darlings

While Compass is grabbing market share in the luxury space, a slew of discount firms are also chasing market share in the U.S.

The latest is Purplebricks, which charges sellers a flat fee of $3,200 for listing a property. Its model seems to be working: The four-year-old startup already has a market cap of around $1 billion. And it’s continuing to expand — last year it launched in Los Angeles after raising $60 million, and last month it debuted in New York. The New York opening came on the heels of a $177 million injection from German media giant Axel Springer.

“Our view is that in 2018 no one should be paying 5, 6 or 7 percent [in commission to a broker] to sell their home,” according to Eric Eckardt, the company’s U.S. CEO. “Look at other verticals today. If you’re going on vacation, you’re not going to a travel agent. You’re going online.”

Venture capital firms are betting that the low-commission model has the potential to go viral and that it will be adopted for sales at all price points — or enough price points to make their investments worthwhile.

In January, the Woodland Hills, Calif.-based REX Real Estate — which uses artificial intelligence to identify buyers — raised $15 million from investors like Scott McNealy, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, Best Buy founder Dick Schulze and former McDonald’s CEO Jack Greenberg.

The firm, which has raised $30 million to date, works with homeowners in California and New York City, charging sellers only 2 percent of the final sale price.

And Redfin — which has a small presence in New York’s outer boroughs — raised nearly $210 million before going public last summer. In 2017, the company’s revenue jumped 38 percent year over year to $370 million.

“Redfin is putting downward pressure on commissions in the markets where they are,” said Real Trends’ Murray.

Still, the company lost $15 million last year.

Halstead CEO Diane Ramirez pointed out that national and international brands have rarely been able to penetrate the New York market. “You get what you pay for,” she said dismissively.

But while New York may be a tough market to crack, if there ever was a way to do it, it’s by promising consumers that they’ll shell out less money for a broker. LG Fairmont seized on that desire, slashing its commissions to 4.5 percent last year, with 3 percent going to the buy-side agent and 1.5 percent to the listing broker.

The good news for traditional brokerages is that others have tried — and failed — in the past.

In the mid-aughts, U.K.-based Foxtons, which also offered discounted broker fees, crashed and burned in New York. In 2007, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy amid a slowdown in the housing market.

But this time around, investors are betting on the fact that consumers will use a discount model — if not for ultraluxury purchases, then for lower-priced transactions.

As real estate prices have skyrocketed, even traditional firms have struggled to charge the standard 6 percent. The market is more solidly at 5 percent, or 4 percent for the market above $20 million, Garfield said last year.

“The old 6 percent on a sale is absolutely a thing of the past,” he said.

The dilemma for firms is that commission fees are dropping just as agents are demanding more and more of a cut, leaving them with a shrinking piece of the pie.

Commission concessions

In the aftermath of Town’s demise, rivals started looting the firm.

In addition to bidding wars over Town’s offices, brokerages wooed top earners like “Million Dollar Listing New York” co-star Steven Gold, Dana Power and Danny Davis. Sources said firms — desperate to boost deal volume — are dangling high commission splits, signing bonuses, lavish marketing budgets and other cash incentives.

“I feel like LeBron heading into free agency,” said one agent.

Ironically, sources said, it was Heiberger who ushered in this latest era of aggressive recruiting by offering high splits when Town launched.

Three years later, when Compass came on the scene, it rewrote the rules again by targeting top agents with bonuses and stock. According to a former staffer, the firm’s business development team pores over agent rankings to determine who to go after.

Compass also allows agents to convert a portion of their commission into stock options — an attractive proposition for those who believe the company will ultimately go public.

While agents might have been loyal to their firms in the past, for some brokers that loyalty has gone out the window as firms offer them better financial packages.

“The way the industry works, what allegiance are you going to have when someone is offering you a 100 percent split?” said MetaProp’s Aarons.

But it’s not just Compass that’s empowered agents to demand higher pay.

Competition for agents has been a driving force in the market, said Jason Deleeuw, an analyst at investment bank and asset manager Piper Jaffray & Company.

This all translates into a hit on the bottom line for firms.

“The impact on profitability is that commission splits go higher when the agents keep more, and that’s less for the [firm],” he said.

To stem their losses, Compass’ rivals have opened their checkbooks.

Last year, for example, Realogy vowed to become a “recruiting machine” to regain market share.

But doing so has been a drag on profits. “Some firms are almost cannibalizing our industry,” said BHS’ Willkie.

Willkie said when he started in the business, the standard commission was 6 percent and no broker received a split higher than 50 percent. Today, BHS pays up to 75 percent to its top earners.

Several years ago, BHS started offering “transition deals.” For newly hired agents who were earning a higher split at their prior firm, the company will match their old split for one year.

But those concessions have come at a price — literally.

Take a hypothetical $20 million condo deal with a 5 percent commission — half for the BHS listing broker and half for the buyers’ broker from another firm.

Assuming a 75 percent split, the BHS agent would take home $375,000 on the deal, while the firm would pocket $125,000. Before those splits shot up, the firm would have taken home far more — $300,000, assuming a 6 percent commission and a 50-50 split.

But some said higher splits are unsustainable.

“I don’t go above 70 percent,” said one brokerage chief. “I won’t make any money.”

According to Lorber, part of the rub is that top agents — who are paid the highest splits — are also doing most of the business in the current market. “If your top broker is getting 70 percent, it creeps up,” he said.

In markets outside New York, splits can be even higher. In Los Angeles, a 90 percent split isn’t uncommon, weighing even more heavily on already-thin margins.

Lorber said that in those markets, Elliman must rely on the ancillary services it offers — like title insurance and mortgages — to offset the high commissions paid to agents.

Elliman’s expansion to new markets has had the biggest impact on margins. “When you open a new market, you lose money for a while,” he said.

Real Trends’ Murray said gross margins are being squeezed, putting pressure on firms to cut costs and remain competitive.

Murray’s firm, which does brokerage valuations, has been hired by a record number of firms looking to merge or sell over the past 12 to 15 months. “People are going, ‘It’s time for me not to fight this battle,’” he said.

But he does think brokerage will live to see another day because brokers, by nature, are entrepreneurial and know how to hustle.

The marketplace dynamics, however, won’t be the same.

“Ultimately, in every marketplace you settle out with some large, low-margin firms and a few high-end or specialty niche firms,” he said. “Everyone else in between gets killed. That’s what happened to Town.”

—David Jeans contributed reporting to this story.