New York is a real estate town.

It’s the home base of many of the nation’s largest brokerages, and the birthplace of the celebrity broker. Deals are bigger, stakes are higher and buyers and sellers are at the zenith of industry, upper-crust society, celebrity or international wealth.

It’s a city where brokers can be kings and queens in their own right, as dealmakers for the world’s dealmakers. Rules be damned when royalty is on the line. Tales of misdeeds run the gamut. Some are agent-to-agent snubs, but others border on the illegal. In recent years, brokers and their shops have come under fire for bullying, discrimination, sexual assault, fair housing violations and attempts to poach exclusive clients.

But despite the market’s reign over the U.S. and the industry’s place at the heart of the city, there’s a hole in the power structure. Brokers at the top are rarely publicly reprimanded, though insider chatter has plenty to report about the behavior of some in their ranks. And what accountability does land in the public eye is often the result of a lawsuit, not an overseer.

It’s enough to sow doubt in the reputation of the industry and raise the question: who’s responsible for the agents?

The answer is unsatisfying: a mosaic made up of the brokerages themselves, the Department of State, which issues their licenses, and the Real Estate Board of New York, the trade group responsible for setting and promoting ethics and professional standards.

But REBNY in particular is on shaky ground, following a slew of lobbying losses, lawsuits targeting its commission policies and controversial changes to the organization’s structure. Some residential agents say they’re losing faith that the group can advocate for them in Albany and City Hall. They are no longer sure it’s strong enough to referee its own games.

Supporters of REBNY credit the group for bringing transparency to a market that was shrouded in secrecy and competition in decades past, and point out that the organization can only adjudicate issues that are brought to its attention with enough evidence for members to take decisive action.

“Enforcement of REBNY’s rules and Code of Ethics is complaint-based, and REBNY cannot guarantee results because complaint evaluation and determinations are peer-reviewed,” the group’s General Counsel Carl Hum wrote in a statement. “REBNY has always and will continue to encourage its members to report violations.”

“Many agents don’t feel their voice is represented,” said Heather Domi, a Compass agent and co-founder of the agent advocacy group New York Residential Agent Continuum. Domi was on REBNY’s board of directors until 2022, when she resigned over criticism that the group lacked broker input in its decision-making process.

Without a track record of listening to residential agents, “I don’t know if people are honestly comfortable going to REBNY with their issues,” Domi said. “The reality is, I think [brokers] just don’t bother.”

Resi’s main watchdog

New York’s Department of State holds the ultimate authority over residential real estate. It issues real estate licenses and enforces the laws that govern them. Run afoul of their rules and you risk losing your ability to sell real estate in the state entirely.

Both consumers and agents can take grievances about agents or entire brokerages to the department, which can impose fines, mandate educational courses and training or, in the most egregious cases, suspend or revoke licenses.

But chances are, a complaint to the agency won’t result in a wayward agent losing a license, except when the department finds a violation as significant as breach of fiduciary duty, commingling client funds or discrimination.

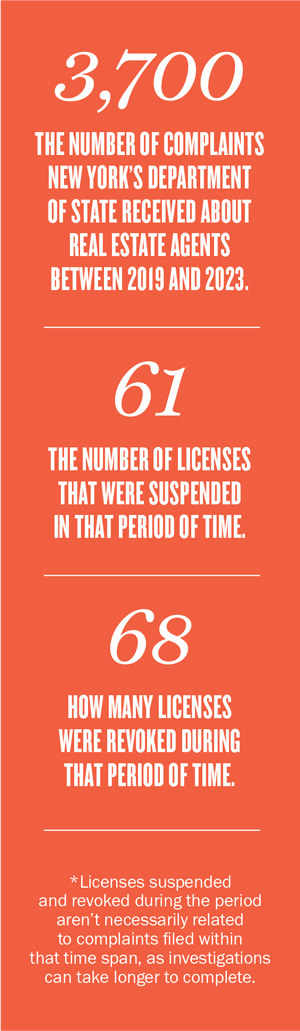

Between 2019 and 2023, the agency received roughly 3,700 complaints about real estate agents, but just 61 licenses were suspended and 68 were revoked — about 5 percent of the total. (Licenses suspended and revoked during the period aren’t necessarily related to complaints filed within that time span, as investigations can take longer to complete.)

“It’s frustrating when the bad apple has the product because you’re forced to deal with them and it makes it incredibly challenging.”

In a similar time period, from 2019 to 2022, the agency completed about 2,500 investigations, 326 of which were referred to the Office of the General Counsel for further disciplinary action, representing about 13 percent of investigations, according to the department’s annual real estate reports. (The agency has not yet publicly released the numbers for 2023.)

New York extended the department’s role in regulating brokers in 2020, after a Newsday investigation found Long Island brokers were discriminating against buyers and renters of color. That year, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a law allowing the agency to revoke agents’ licenses for discriminatory practices. Gov. Kathy Hochul last year expanded an undercover testing program meant to curb discrimination, but the state paused the program in September citing issues with the funding and timeline.

“There’s been bad behavior in real estate for far too long without any real consequences,” Domi said after Cuomo expanded the agency’s purview. “Our industry needs more of a watchdog.”

A year later, a housing advocacy group sued several brokerages for allegedly violating fair housing laws and discriminating against Section 8 voucher holders. Last year, another lawsuit made similar accusations of some of the city’s star brokers, all with Douglas Elliman at the time of the allegations. That complaint claimed that some defendants did not understand what a Section 8 voucher was, even though state law requires fair housing training for those who obtain real estate licenses.

The lawsuit named top brokers Noble Black, Holly Parker, Frances Katzen and Tamir Shemesh. Elliman said it had a “zero tolerance policy towards unfair and illegal treatment of any individual or group.”

Brokerage burden

Top brokers, brothers Oren and Tal Alexander, rose to the top at Douglas Elliman over a decade. All the while, they allegedly drugged, raped and sexually assaulted women, mostly in New York, according to lawsuits and reporting first published by The Real Deal this summer.

One industry pundit dubbed the allegations the “worst-kept secret” in real estate. Although the brothers now own their own firm, Official, the news raised questions within and outside the industry about how their rumored actions could have flown under the radar for so long. Elliman faces allegations that its top executives knew about at least one incident of drugging. The firm maintains that the incident was never tied to the Alexanders and that no formal complaint was ever made.

Brokerages are the first and often only stop for resolving complaints about agents’ behavior or conflicts between brokers. But brokers at most firms are independent contractors, not employees, and they’re not always subject to the same rules and procedures as say those imposed by a human resources department.

There’s also an obvious conflict of interest when it comes to top producers. Brokerages make money when their agents make money, and managers and executives have long been criticized for turning a blind eye to bad behavior among top earners.

A year after Christopher Burnside was sued for having sex with his subordinate in his clients’ home, for example, Brown Harris Stevens celebrated him as the top performer in the Hamptons and the third highest-grossing agent at the firm.

According to a lawsuit, the clients’ security cameras caught Burnside’s “sexcapade” with his associate, Aubri Peele, when the two were supposed to be hosting an open house. Despite the accusations, Burnside and Peele still work on the same team at BHS, and it’s unclear whether the firm ever formally disciplined them. At the time, BHS CEO Bess Freedman told TRD that the firm would find “an appropriate resolution.”

Even when brokerages do step in, they often stay silent about the circumstances of an agent’s resignation or dismissal. Early last year, Serhant fired former top broker Tamir Shemesh. The brokerage declined to share the reason behind his termination, but his ousting marked Shemesh’s third abrupt exit from a firm in seven years.

When REBNY steps in

Problems that fall between the cracks of brokerages and the state become the province of REBNY. New York City doesn’t have a multiple-listing service or a local chapter of the National Association of Realtors, but REBNY’s role is similar to that of a Realtor association. It’s a state- and local-level advocate for the industry, and it has rules governing the use of its residential listing service, the city’s local MLS. Its code of ethics is enforced by control over who has access to the RLS.

Members of REBNY have to abide by the Universal Co-Brokerage Agreement, the document outlining the rules of the road for the RLS. The agreement dictates how and when listings should be uploaded to the RLS and what information should or shouldn’t be included. Noncompliance brings fines of up to $500 for a first offense or $10,000 for three or more violations in the same 12-month period. Other punishments include a notice of offense posted to the group’s website or revocation of access to the RLS — either temporarily or forever.

But the group’s purview over broker behavior is more closely tied to its code of ethics. The code forbids defaming other brokers or brokerages, sharing confidential information without a client’s consent and falsely claiming to be an exclusive listing agent, among other offenses. Members who suspect others of violating the code can report them to the group. A member panel hears code of ethics violations; its decisions can be appealed.

Public consequences for brokers breaking the rules are few and far between. When asked, several brokers recalled just one instance of a public censure in recent memory, which some chalked up to a slap on the wrist.

The group censured Tal Alexander, then at Douglas Elliman, in 2022 over a complaint that he interfered with an exclusive relationship between Fox Residential’s Barbara Fox and her client during a deal at Beckford Tower a year prior. The penalty made headlines but didn’t seem to leave a dent in his business.

That same year, Tal and his brother Oren, who had headed the Alexander Team, founded Official and landed among the top 30 resale and new development agents with roughly $230 million in sales across both categories. A year later, their firm came in at No. 8 of the top brokerages in Manhattan.

REBNY’s critics argue that trust is faltering among its members in part because the group lacks a track record of imposing penalties, and that even its worst punishment, losing access to the RLS, isn’t enough to compel agents to follow the rules.

Hum, REBNY’s general counsel, said in a statement that the organization “has an established track record in adjudicating complaints among its members and disciplining them, when applicable.” He pointed to the need for formal complaints in order for issues to be addressed, and noted that complaints are peer-reviewed.

Agents’ frustrations with REBNY are the local manifestation of a larger shift in the industry, which is in the midst of a reckoning over how agents do business and who sets those standards.

The antitrust lawsuits over agent commissions, plus the spate of other legal action, have put trade groups’ role in setting standards front and center. Public trust in the industry’s ability to self regulate was already low, and an age-old contradiction in their mandate may be making the situation worse. Though associations, across industries, tout their importance as ethical leaders, they often face a conflict of interest when it comes to policing their members, according to professors, including Rutgers University’s Michael Barnett and Butler University’s Lawrence Lad, who study self-regulation within industries.

To be vigilant would mean cracking down, and potentially losing out, on the same constituents paying membership dues and donating money to the organization.

“It’s like the fox guarding the hen house” is how experts characterize the dichotomy.

But REBNY’s supporters credit the organization with improving the ethical and professional behavior among agents. Bill Sherman, who co-chairs a REBNY committee, said this is visible in pockets of the outer boroughs and Westchester — areas outside of REBNY’s domain. There, he claims he consistently runs into issues with agents who refuse to cooperate, unlicensed agents handling deals or agents who don’t comply with other practices common in Manhattan, REBNY’s turf.

REBNY loses its grip

Confidence in REBNY faltered after a series of public losses that showed a weakness in its lobbying power. First came Local Law 97, then the rent stabilization laws of 2019, followed by the end of the 421a tax break and now a looming agreement to settle the antitrust lawsuits, though the terms have yet to be announced.

The group also still hasn’t managed to squash a City Council bill aimed at shifting the burden of paying broker fees from tenants to landlords, which has put the misdeeds of rental brokers front and center in the minds of New Yorkers.

“There are bad actors here, which is why we are in this situation,” Council member Sandy Nurse said at a hearing on the bill in June.

Tenants, brokers and executives showed up to the hearing in droves to rally for and against the legislation. Tenant after tenant shared stories about arriving at units advertised as no fee only to find out they would have to pay a broker after all, which is against rules that require listings to advertise all fees and costs associated with renting the property.

“I do not think that there’s any reason for me to pay one month’s rent or more to a person the landlord hired to post something on StreetEasy, or Zillow, or God-knows-where, riddled with typos and lies only for me to get the apartment on my own and not get any response to my basic questions,” said Annie Abreu, who lives in Sunset Park, Brooklyn.

The criticism of rental agents landed back on REBNY, with some brokers calling out the group for protecting the interests of its landlord members over residential agents.

“REBNY does not represent agents,” said broker Jeffrey Hannon, who started his solo shop after leaving Douglas Elliman. “They represent corporate landlords, and they’re lying to their agents.”

A spokesperson for REBNY pushed back on that characterization in a statement, touting its role as an “advocate on behalf of our members as the voice for New York City’s real estate industry” and adding that the organization has sued the state of New York on behalf of brokers, fought tax proposals they say would affect the industry and pushed back on City Council laws to eliminate broker fees.

Though the industry, including REBNY, has mobilized against the bill, nearly two-thirds of the City Council supported the legislation in September, when it was added to the Democratic conference agenda; they’re expected to vote on the bill this month.

Good apples

Some brokers say there is a greater force than REBNY for setting the standard of behavior among brokers: the city’s fast-paced, unrelenting market, which ultimately dictates how agents interact with each other.

A relatively small share of brokers controls most of the transactions in the city, and some argue that this limited pool of players keeps most agents in line, compared to markets like South Florida, which are more like the Wild West.

Reputation and relationships with other brokers is “the secret sauce,” said R New York’s Stefani Berkin, and garnering a bad one can be a death knell to business.

“It’s the difference between winning bidding wars or getting your client into a new development building that’s impossible to get into,” Berkin added. “It’s frustrating when the bad apple has the product because you’re forced to deal with them and it makes it incredibly challenging. But sometimes we have to deal with difficult people.”

The same could be said on the flipside.

With higher stakes comes more competition among the short list of clients who power the top of the market. Seeing the same few names routinely towering above the rest means that reporting bad behavior is a tall order for those who aren’t among their ranks — like a nerd reporting the prom king.

With REBNY showing signs of weakness, some brokers hope another organization will step in and take over the helm. Berkin’s R New York was the first major brokerage to join the American Real Estate Association, or AREA, a national trade group founded by Compass agent Jason Haber and the Agency’s Mauricio Umansky, which is presented as a rival of NAR on the national stage. But brokers like Berkin are hoping their involvement will set the stage for the next generation of leaders.

“The reason that I’ve been so outspoken about AREA, and the reason I’m part of the advisory board, is because I don’t think we have an organization in New York that is for agents by agents that are young, forward-thinking and sophisticated,” Berkin said. “It’s easy for decisions to get made when you’re not the one with boots on the ground.”

But, she added “the industry needs it so badly.”

Editor’s note: This is the third story in TRD’s investigative series covering the under-regulation of real estate agents and brokers.