On her first full day as First Deputy Mayor, Maria Torres-Springer was stuck in traffic.

She was on her way to an empty, weed-covered parking lot in Inwood to celebrate the site’s future as 570 units of affordable housing. The project was part of the Adams administration’s pledge to advance 24 projects on city-owned land this year, dubbed 24 in ’24.

The underlying message of the press conference appeared to be that amid a widening scandal inside the Eric Adams administration, key housing initiatives would move forward.

Torres-Springer never made it to the unkempt development site, but she still collected praise for her constancy.

“She is a person of incredible integrity and tremendous experience, [with] a history of having worked with three mayoral administrations, in almost every capacity, including my job today,” Department of Housing Preservation and Development Commissioner Adolfo Carrión said, brushing away a question about how Torres-Springer’s elevation would affect workloads in his 11 departments.

Torres-Springer, who served in multiple roles under Mayor Bill de Blasio, including president and CEO of the city’s Economic Development Corporation and head of HPD, was deputy mayor for Housing, Economic Development and Workforce for Adams and is still overseeing her housing and economic development portfolio as she steps up.

A few clicks down the org chart and you find another Torres-Springer type: Kim Darga, a 17-year HPD veteran who is now deputy commissioner of the development office, one of Carrión’s units.

Torres-Springer and Darga are emblematic of a class of government stalwarts, loyal but stretched thin, ready to provide context and expertise and keep city business moving — even when there are problems as big as staffing shortages or as enormous as a federal corruption investigation.

She and her teams work with developers on new construction and preservation projects, tax breaks and incentive programs, architecture and engineering support and city subsidies that go to affordable rental and homeownership projects. Multifamily developers spend a lot of time emailing, calling and, almost certainly in some cases, privately cursing this office as they wait for financing to close. Darga’s office is the bureaucracy, at least to the real estate industry.

At the beginning of Adams’ term, part of the agency’s mandate was to cut red tape and streamline processes to make building housing in the city easier. That mission was threatened first by pandemic recovery and, now, an administration in distress.

Outside of government, the real estate industry has mostly stayed mum on a mayor they can no longer easily support, even though they dislike his opponents’ politics. Yet inside, things chug along, with old hands like Darga increasingly important for priorities, especially its housing aspirations, even when the landscape for their work is more disorderly than a weed-strewn Upper Manhattan lot.

The task at hand

When Kim Darga took over a high school classroom in the middle of the school year, the departing teacher gave her a care package with Tylenol, hand sanitizer and a spa kit. The message was: You are going to need this.

Darga lasted two and half years but concluded that she was not patient enough to teach.

If you have ever heard Darga testify at a New York City Council meeting, this may come as a surprise: She walks City Council members through intricacies of housing finance, explains why a policy proposal is redundant and calmly responds to questions she has already answered.

“It’s an educational opportunity,” she said in an interview.

“There is no published list of projects and a scoring system for projects that are closing at any given time. You can be in the queue for several years, without any understanding of when your project will close.”

She arrived at HPD in 2007 as a project manager. She did not think she would stay with the agency for more than two years, but she admired the drive of her coworkers.

“This is a place where people are really dedicated to the work,” she said. “They may not always agree on everything day to day, but it’s the dedication to the work that drives the conversation.”

She stayed. Her current deputy commissioner job has been a stepping stone to the commissioner role for some of her predecessors, including RuthAnne Visnauskas, who now heads the state housing regulator; Rafael Cestero, CEO of the Community Preservation Corporation; and Eric Enderlin, president of the Housing Development Corporation, the city’s housing finance arm that works closely with HPD.

The city’s housing agency was formed in 1978. In the following decade, as the federal government drastically pulled back on financing housing construction, the Ed Koch administration turned it into the steward of mayoral housing ambitions. The agency was charged with executing the mayor’s 10-year housing plan, regarded as the first of its kind, by finding developers to rehab properties seized by the city.

This role endured under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s New Housing Marketplace Plan, which set a goal to build or preserve 165,000 units by June 2014, and then Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Housing New York.

The Adams administration initially moved away from declaring a specific unit count.

“If you say 30,000 and you have 50,000 that are homeless, then what success is that? I got 20,000 people that are not [housed]. So I’m not at this magic number,” he said in 2022. “I’m going to get as many people, in my four years, into housing as possible.”

He later reversed course by setting a self-described moonshot of 500,000 homes over the next decade. Even before the mayor’s legal woes, this sum seemed improbable.

HPD’s development office contributes to this goal by financing the creation and preservation of affordable housing. It works with city funding, various tax exemptions and, alongside the Housing Development Corporation, combining these resources with federal tax credits and bonds. In fiscal year 2024, HPD spent nearly $2 billion in city subsidies on building and preserving affordable housing.

This process can be slow.

During a hearing in October, City Council member Rafael Salamanca, who chairs the land use committee, asked Carrión why financing for projects closes years after members approve them.

HPD has 750 projects in the pipeline, Carrión said, of which 300 are ground-up construction.

“These are complicated projects in a crowded field of projects,” he said.

In a nod to the agency’s need to boost its resources, especially in the wake of the pandemic, HPD’s development division was spared from certain budget restrictions that would have capped hiring. New permanent and temporary staffers have helped move projects along, Carrión said.

“It is still obviously not fast enough,” he said.

Internal affairs

The agency’s development unit draws a lot of talent, attracting graduates with urban planning degrees, accountants and those with finance expertise who could make considerably more money working for Wall Street or private companies.

“That’s kind of unique for a city agency. The problem with that is there is a lot of turnover in that group,” one person who previously worked for HPD said. “You build up a huge amount of talent, and then people leave in a year or two.”

Turnover means losing institutional knowledge and the kind of consistency that comes from years of experience. One affordable developer, who asked to remain anonymous, said working with the senior team at HPD is great but expressed frustration about agency newcomers.

“You end up having a really difficult time,” he said. “You are constantly explaining.”

The pandemic exacerbated staffing challenges, along with hiring freezes and state rules around hiring government employees that slow the process. The administration doubled down on city workers returning to the office full-time in 2022, but City Hall eventually had to reverse the policy, as employees left for jobs — often higher-paying ones — with more flexible schedules.

“If you are a manager, and all you can do is say thank you to your superstars, you are not going to keep them,” a source familiar with the agency said.

At one point the development division was down 232 people, or roughly 33 percent. The agency has gotten that number down to 20 percent and has hired temporary employees to help work through its backlog.

“They’ve actually, to their credit, been able to turn it around,” Juan Barahona, founder of SMJ Development, said. “Now the challenges are: there are just so many projects coming to them, how to make a project compelling enough to grab their attention?”

Vacancies translate to larger workloads for those left behind.

“When someone leaves HPD, they aren’t like ‘OK we should do less,’” said one person with knowledge of the inner workings of the agency. “HPD doesn’t do a lot of reappropriating…they would just sort of hope that someone steps up.”

One source described HPD as a corporation with different businesses that, depending on leadership and talent “can work really well together or not at all.”

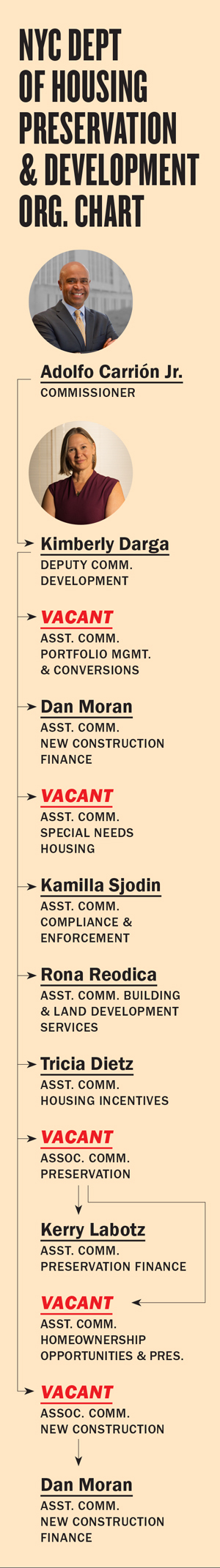

Under Darga, there are eight assistant commissioner positions, each of whom oversee a division within the development office. Two associate commissioners, one for new construction and one for preservation finance, usually oversee three of the eight assistants.

Darga had been associate commissioner of preservation finance until April 2022, but her old role is still vacant. So too is the other associate commissioner role and three assistant commissioner positions, though two of those — supportive housing and homeownership opportunities — have acting assistant commissioners who are expected to be made permanent soon. Darga said the agency is interviewing for the third role, which oversees HPD’s portfolio, but is not looking to fill the associate commissioner positions. There will be some restructuring, she said.

Kerry LaBotz, assistant commissioner of preservation finance, recalled that all of her directors left at one point, leaving just her and a few project managers. (The agency’s preservation and transactional teams lost about half their staff during the pandemic.) She credits Darga with providing support and helping to manage expectations about what the unit could realistically do under its staffing constraints.

“Having that sort of senior-level advocacy when there are vacancies at the lower levels is really important to keep things sane,” she said.

LaBotz and Tricia Dietz, assistant commissioner of housing incentives, who is working with developers on the 485x tax break, both said there was a supportive culture and a feeling that they could make an impact.

“I think we try to fill gaps where they exist,” Dietz said. “I think that there’s just a strong culture of mission and trying to have that work get done to the extent that we can.”

Dealing with developers

Not every developer’s experience with HPD is the same, and it is easier to feel warm and fuzzy about the agency if your project is progressing. An affordable housing developer who spoke to The Real Deal called the agency a “black box” because it is unclear what deals it prioritizes.

“There is no published list of projects and a scoring system for projects that are closing at any given time,” the developer said. “You can be in the queue for several years, without any understanding of when your project will close.”

“That length of time is prohibitive for a lot of people,” they continued. “You could easily be carrying several million dollars of predevelopment costs.”

One industry source said the agency has a preference for doing business with firms it has already worked with.

“Like anybody else in real estate finance, they are risk averse. They are financially risk averse, and politically risk averse,” they said. “Bigger players go to the front of the line.”

Developer Hal Fetner praised the development office.

“As I took three different projects through Ulurp, all the way to closing, and now lease up, for the most part I’m still dealing with the same people I was dealing with five or six years ago,” he said. “They have been true partners to Fetner on developing affordable housing.”

Barahona, the SMJ Development founder, said he approached LaBotz about 351-357 West 45th Street, distressed rental buildings in Hell’s Kitchen that nonprofit Services for the UnderServed, Highpoint Property Group and SMJ acquired from Steve Croman in June. The buildings did not seem to fit neatly into any one city program.

“We kind of worked together to figure out what it could be,” he said.

The development team will use nearly $20 million in low-interest loans from HPD to renovate the buildings and plans to enter a 30-year masterlease agreement with the Human Resources Administration as part of a new program that uses city vouchers to renovate or build affordable housing for formerly homeless people. The goal is to renovate the homes of 11 current rent-stabilized apartments and restore the remaining 69 apartments for families referred from city shelters.

“They are very nimble and creative at HPD, at least that’s been my experience,” he said.

Not out but through

At a meeting in September, Darga testified that a proposed bill, which would require a certain percentage of city-funded projects be put up for sale rather than rented, would sap city resources.

She said setting a specific threshold would “potentially result in money or projects left on the table.”

Members of the administration utter a similar refrain at City Council hearings: “HPD supports the goal of [insert bill number here].” It is a diplomatic way of saying “this bill doesn’t work.”

With the rise in interest rates and construction costs, city dollars do not go as far as they used to, even a few years ago, in funding housing.

“We’re trying to do as much as we were five years ago, without the resources to necessarily do it,” Darga said.

The agency is often in the position of managing expectations on both ends — private and public — because it has limited subsidies to work with.

In fiscal year 2024, the agency financed the creation and preservation of 25,266 affordable units. More than half of those units were newly constructed, but those numbers were boosted by projects that were able to qualify for 421a before it expired in June 2022 — in previous years before the tax break’s expiration, preservation starts outpaced new construction by thousands of units.

Still, even with constraints on how many deals HPD can close each year, real estate attorney Ken Fisher said the agency appears “very eager for people to bring them deals.”

“They’ve all gotten the memo that this is the moment for affordable housing production,” he said.

How long can such momentum last?

The mayor’s signature housing policy, a series of zoning changes dubbed “the City of Yes for Housing Opportunity,” lies with the City Council.

In what shape the proposal makes it through will be a test for the embattled administration and may show how much leverage the Council has as the mayor fights criminal charges. It is not clear how long Adams will remain mayor, whether he is removed, steps down or must defend his position in the 2025 election.

Whatever course his tenure takes will likely shape budget negotiation next year and the senior leadership at HPD and other city agencies.

Commissioner Carrión’s name was floated to run a newly formed landlord group last year, but at the time, he denied wanting to leave HPD, and the group ultimately selected someone else. He hasn’t otherwise publicly indicated any plans to step down.

As negotiations on City of Yes and the Adams scandal play out, Torres-Springer’s first priority “is to make sure that we continue to be super focused on the work,” she recently told CBS. Leaders are making reviews of “programs, of processes, of personnel, to make sure that we as an administration maintain the strength that is needed to deliver for New Yorkers.”

Back at HPD, the teams are continuing the step-by-step work of modernizing the bureaucracy. The agency launched a pilot program to outsource to nonprofit lenders some of the paperwork involved in financing moderate renovations of rent-stabilized properties. It also started classroom-based training to get agency newbies up to speed on housing development and finance.

Additionally, HPD has funding for a digital project management system that will accept application materials from developers in one place, rather than relying on email and Dropbox, Darga said.

The pandemic had shown them that their disorganized, outdated system of collecting project information was bogging them down. As people left the agency, developers would have to start over with new project managers who couldn’t even find logs of what had been done on a project.

“I know this is so geeky, but I have to say this is one of the things that I will maybe be most proud of,” Darga said of the new system.

Darga, who said the mayor’s legal troubles haven’t impacted her work, remains hopeful this system could help address some developer criticism. But she also thinks the industry is coming to grips with HPD being under-resourced at a particularly tough economic and political moment.

“It’s a lot of just continuing to talk about timing and helping people understand the resource environment that we’re in,” she said. “We’re committed to moving the forward projects forward, but it can take some time.”