Masayoshi Son was widely regarded as an eccentric-but-gifted entrepreneur when, in 2014, he dazzled investors during an earnings presentation by showing them a picture of a large, brown-feathered bird.

“SoftBank wants to become the goose that lays the golden eggs,” Son told them, two years before launching a $100 billion Vision Fund that went on to anoint a crop of promising startups.

But over a turbulent six weeks starting in September, one of its biggest bets went south when WeWork scrapped plans for an IPO, saw its valuation plunge to less than $8 billion from $47 billion and ousted its co-founder and CEO, Adam Neumann.

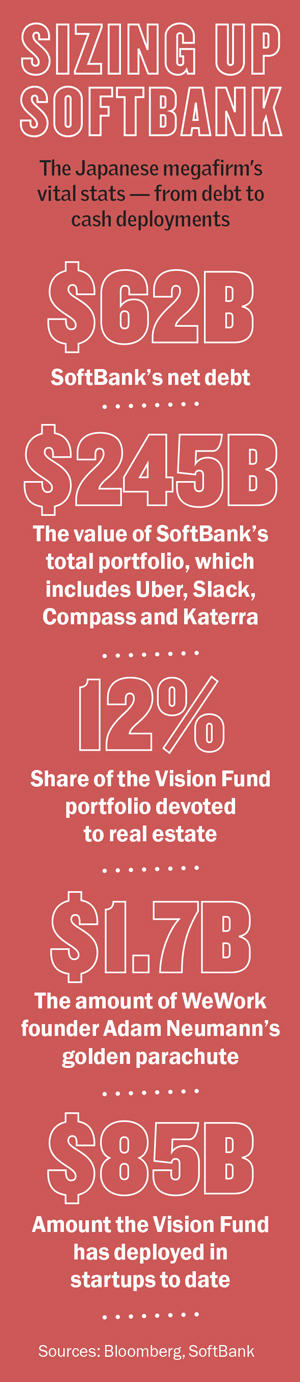

The co-working company — which lost $900 million during the first half of 2019 — was on the brink of insolvency when SoftBank threw it a $9.5 billion lifeline.

In the wake of that spectacular downfall, many are now questioning Son’s strategy of dumping massive amounts of cash on unprofitable firms. Although cherry-picking startups and supersizing their growth made Son a kingmaker, the tactic is now facing harsh criticism, with some saying it’s stoked a trend of overvaluing companies.

Ed Zitron, founder of the San Francisco-based tech-focused PR firm EZPR, mocked Son right after WeWork’s implosion last month.

“Masa Son! I reach out to you with the greatest salutations! I would like to offer you a deal – one billion dollars of your soft bank [sic] fund and I will make a terrible company and lose all of the money!” he tweeted.

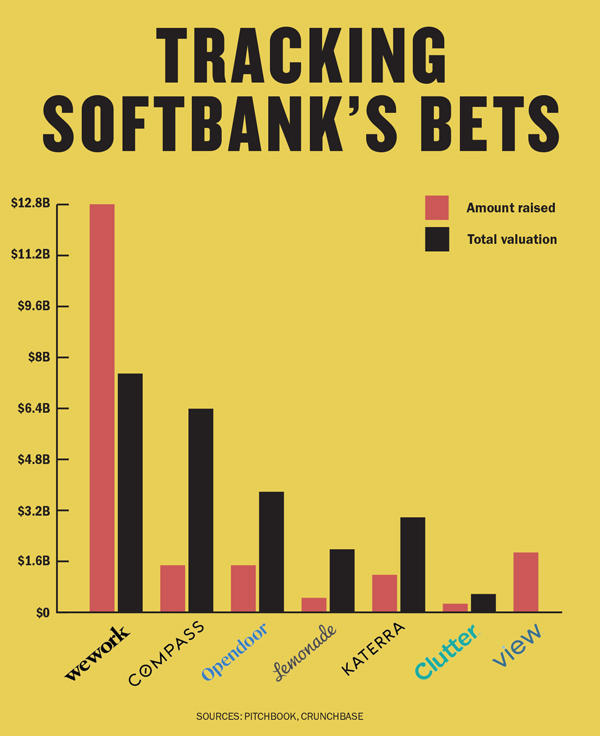

The playful needling underscores increased scrutiny on other companies SoftBank has backed — including Compass, Opendoor, Lemonade and Katerra.

“SoftBank’s Vision Fund has become the poster child for what many believe is a bubble in private market valuations of technology stocks,” Walter Piecyk, an analyst at research firm LightShed Partners, wrote in mid-October. “In fact, many blame SoftBank for driving up industrywide valuations across multiple verticals, whether SoftBank was an investor or not.”

SoftBank has, indeed, helped fuel other massive funding rounds in the venture world, where there’s now increased pressure to land a lottery-style win. Since the end of the financial crisis, investors have poured hundreds of billions of dollars into high-risk startups.

“The SoftBank/Vision Fund investing philosophy is the sharp tip of the spear,” said Hong Kong-based analyst Jeffrey Halley, explaining that it’s been the most aggressive investor in the field.

“The SoftBank/Vision Fund investing philosophy is the sharp tip of the spear,” said Hong Kong-based analyst Jeffrey Halley, explaining that it’s been the most aggressive investor in the field.

With too much dry powder, many venture capitalists have looked outside their typical investment parameters into high-risk deals, said Halley, who works at Oanda, the foreign-exchange firm.

“The market,” he added, “ignores realities and convinces itself in a massive groupthink that ‘this time it’s different.’”

“Embarrassed and impatient”

The timing of WeWork’s downfall couldn’t be worse for Son, who is trying to raise a second Vision Fund — this one for an estimated $108 billion.

In early October, some SoftBank executives reportedly urged him to delay the offering because he was struggling to raise the cash.

In September, at a five-star resort in Pasadena, California, Son told a group of entrepreneurs — whose companies were backed by SoftBank — that they need to become profitable soon, according to published reports.

And in recent weeks, Son has said publicly that he was “embarrassed and impatient” with SoftBank’s recent track record. During an investor call late last month, he apologized to investors in the first Vision Fund, according to Bloomberg.

LightShed’s Piecyk, however, said in his report that it’s not the “size of the possible investment losses at WeWork” that are most concerning. “It’s the ongoing damage to SoftBank’s reputation and how that might limit future investing,” he wrote.

The global stock markets share those concerns. SoftBank’s stock — down 30 percent since July — slid even more on news of the WeWork bailout.

“This sorry episode is also a searing indictment of SoftBank’s valuation and screening methodology which needs to shift towards being based on fundamentals rather than blue sky,” Richard Windsor, founder of the research company Radio Free Mobile, wrote in a research note.

While companies like Apple and Foxconn, the electronics manufacturer, are contributing to the Vision Fund 2, Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia — two of the biggest investors in SoftBank’s previous fund — haven’t confirmed their commitments.

SoftBank (and other companies) took flak for accepting money from Saudi Arabia after Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi was killed at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul last year. But while some investors initially shunned Saudi leader Mohammad bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (aka MBS), Son — who raised $45 billion from the kingdom for the first Vision Fund — stayed with him.

With that controversy behind it, sources said, SoftBank must now worry about its reputation among investors in the wake of WeWork’s failed IPO.

Although SoftBank’s first Vision Fund earned $1.5 billion on its investment in Flipkart, an Indian e-commerce company, Uber’s public offering was widely considered a flop.

Sources close to Son have reportedly said he’s considering a more cautious strategy for Vision Fund 2. The SoftBank chief will focus on companies with clear paths to profitability and is likely to slow the frenetic pace of investment. The first Vision Fund deployed roughly $80 billion within two and a half years; Vision Fund 2 will be deployed over four to five.

Some observers, however, said the WeWork bailout represents a second chance for SoftBank to make good on one of its biggest bets.

“These are grownups. These are all consenting adults,” said Rett Wallace, founder of Triton Research, who added that SoftBank can “well afford” these sorts of losses. “It makes sense for them to keep [WeWork] going rather than walk away from it, abandoned on the side of the road.”

How SoftBank will right-size the co-working giant remains to be seen.

After adding 6.3 million square feet of office space in the U.S. and Britain last year, the co-working firm was on track to take another 9.9 million square feet this year, according to data from CoStar Group. But it’s unclear whether WeWork will follow through on those lease commitments — or if some of the landlords it struck deals with will be left holding the bag. In mid-October, WeWork scrapped plans to lease an entire 36-story office tower in Seattle.

“If SoftBank turns WeWork around with the decks cleared … the fallout should be limited,” Halley said. “Much will depend on how the next few SoftBank-invested exits go over the next six months.”

Keeping distance

Amid WeWork’s reckoning, other SoftBank-backed firms have tried to distance themselves from the spectacle. In a company-wide email sent early last month, Compass CFO Kristen Ankerbrandt posited that it was hard to draw any parallels between the firms.

Compass and others have argued that unlike WeWork — where SoftBank holds an outsized stake — they have benefited from diverse investor bases. (Following the bailout, SoftBank, which has invested $13 billion in the company to date, held a roughly 80 percent stake in WeWork.)

By comparison, SoftBank has contributed just over a third of the $1.5 billion raised by Compass, company officials said. In an interview at the residential brokerage’s Manhattan headquarters last month, CEO Robert Reffkin also downplayed SoftBank’s role in determining Compass’ valuation of $6.4 billion, which he said was set by multiple investors including the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Dragoneer Investment Group and Glynn Capital Management.

“It’s a number of third-party investors, who are much smarter than I am, that do this for a living,” Reffkin said.

Katerra CEO and co-founder Michael Marks, meanwhile, told The Real Deal last month that his company is “not at all like WeWork.”

VCs that invested alongside SoftBank in Opendoor — the San Francisco-based iBuying startup that’s raised $1.3 billion in equity and $3.5 billion in debt financing since 2013 — are also downplaying SoftBank’s role.

“SoftBank is a relatively small minority of capital Opendoor has raised,” said David Weiden, a partner at Khosla Ventures, which has invested an undisclosed amount in the company.

In March, Opendoor closed a $300 million round at a $3.8 billion valuation from investors including SoftBank, General Atlantic, Lennar Corporation, Fifth Wall Ventures and others.

SoftBank declined to comment, but a source close to the Vision Fund said it measures fair market value in accordance with international private equity, venture capital and accounting standards.

Yet amid increased competition, Opendoor began curtailing expenses this spring — laying off 50 out of 1,300 staffers and asking 200 to 300 others to relocate to Phoenix. The company also pulled the plug on free lunches.

And Compass halted launchings in new markets this year. Instead, it’s focusing on its existing markets. But in a pointed rebuke of Neumann’s $60 million private jet, Compass said all of its execs fly commercial. (Notwithstanding Chairman Ori Allon’s flight on a private plane to the Bahamas this year, according to his Instagram.)

On Oct. 17, Reffkin posted a selfie from what appeared to be the coach cabin of a flight from New York to San Francisco. “If anyone wants tips on how to fall asleep on a redeye,” he wrote, “I’m happy to give you some great tips!”

The SoftBank fallacy

SoftBank’s presence has turned the VC landscape on its head in the last few years.

Amid stiff competition for the most promising deals, many investors simply overpaid by valuing companies based on metrics they expected to see in the future.

As of 2019’s third quarter, there were a record 180 VC-backed companies valued at over $1 billion, according to the data analytics site CB Insights. Helping fuel that were more than 120 companies that received over $100 million apiece during the second and third quarters.

The danger of inflated valuations, though, has become clear.

Tech startups that went public in 2019 have faced a cool reception in the public market.

In late October, for example, the stock price of instant-messaging firm Slack was down more than 47 percent since its June IPO, and Uber’s was trading at nearly 20 percent below the IPO price. Both were backed by SoftBank.

And it’s not just investors who were burned.

After SoftBank’s bailout, thousands of WeWork employees were bracing for mass layoffs, but those cuts were delayed because the company couldn’t afford the severance payments. In addition, under the bailout plan, employees who opt to sell their WeWork shares to SoftBank will do so for less than the paper value of the stock when it was issued.

“It is not unusual for the world’s leading technology disruptors to experience growth challenges as the one WeWork just faced,” Son said in statement at the time of the bailout.

Many WeWork employees were also irate over Neumann’s golden parachute (he got $1.7 billion to walk away from his board seat) and his reckless spending and self-dealing. “I don’t know why anyone was paying him for the word ‘we,’” one former executive told TRD in September. “The only word he knew was ‘I.’”

But the problem is bigger than Neumann.

Merritt Hummer, a senior principal at Bain Capital Ventures, said it’s become common for VCs to overpay for a stake in sought-after companies.

“It’s become not the exception but the rule for companies that are performing,” she said.

“The SoftBank fallacy, if you want to call it that, is that they’ve applied this methodology to companies that are mature,” she added. “That is risky to do when you’re the last capital in and the next decision-maker — in terms of a valuation of the business — is going to be the public market.”

—David Jeans contributed reporting.