UPDATED: Aug. 1, 6:14 p.m.: What do George Washington, rapper Lil Wayne and actor Jeff Goldblum have in common? They all appeared earlier this year in a Super Bowl television commercial sponsored by the CoStar Group.

The Washington, D.C.-based real estate data provider in February ran the ad for its residential listings site, Apartments.com, reportedly paying as much as $5 million to produce it and $20 million for the airtime. In the one-minute spot, Goldblum, seated at a grand piano and singing “Movin’ on up,” is hoisted up the side of a skyscraper, to a palatial rooftop terrace, where he joins Lil Wayne and an actor playing the nation’s first president for a cookout. The commercial — which also featured a gospel choir of movers — was an absurd bit of promotional fluff, but it showed just how serious the company’s ambitions are.

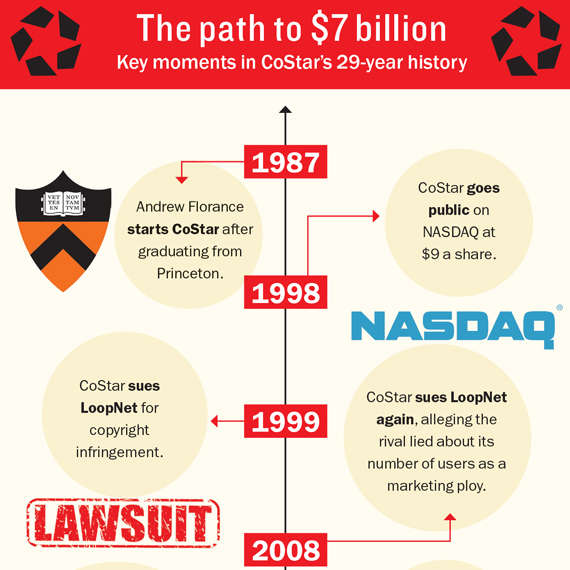

To put it simply, CoStar, which has an unrivaled trove of data spanning more than 4.2 million commercial properties and has long been considered an indispensable tool among brokers, property owners, banks and even large retailers, is seeking to become a household brand. Over the past four years, it has spent $1.6 billion buying up real estate data companies, securing its stronghold on the commercial side, as well as breaking into the residential market. In 2012, CoStar bought the commercial listings site LoopNet for $860 million, an acquisition that allowed it to fold in data from the popular crowdsourced site. Two years later, it dished out $585 million for Apartments.com, the second-largest apartment-listings site in the U.S., behind Zillow. And just last year, CoStar snapped up Apartmentfinder.com for $170 million.

But the company’s expansion — more than 20 acquisitions in nearly 30 years — comes as some in the real estate industry grow increasingly leery of the data behemoth’s market power. The company is famously litigious. Since 2004, CoStar has filed at least 31 federal lawsuits against users and competitors, court records show.

Rival entrepreneurs have accused the company of using its heft to stifle competition, and some brokers and observers complain that the firm’s dominance leaves them little choice but to pay its hefty prices for the lack of any alternatives. Michael Mandel, a former leasing broker at Grubb & Ellis (now Newmark Grubb Knight Frank [TRDataCustom]) who in 2011 founded CompStak, a commercial database company that lets users trade leasing comps, said access to CoStar is critical because it has almost every lease listing in major markets. “If you’re a leasing broker in one of these markets, there’s no way that you can do your job without a CoStar account,” he told The Real Deal.

CoStar declined requests for an interview, but released a statement from CEO Andrew Florance defending the company’s legal actions. “CoStar is very proud of the innovative technology its security and legal teams have successfully deployed to detect and stop online illegal activity,” the statement read. “CoStar will continue to take all necessary steps to aggressively stop theft and fraud.”

CoStar declined requests for an interview, but released a statement from CEO Andrew Florance defending the company’s legal actions. “CoStar is very proud of the innovative technology its security and legal teams have successfully deployed to detect and stop online illegal activity,” the statement read. “CoStar will continue to take all necessary steps to aggressively stop theft and fraud.”

A research powerhouse

By all definitions, CoStar has had a remarkable ascent. The company was started in 1987 by Florance, the son of a well-known architect in Washington, D.C. While still an undergraduate at Princeton University, Florance noticed a gaping hole in the real estate market and embarked on creating a centralized source for commercial property data. Not long after, CoStar was born. In 1998, Florance took the company public.

Since that time, CoStar, which trades on the Nasdaq, has seen its share price rise from $9 to around $220 as of mid-June. The company, which has 2,500 employees around the globe, now has numerous products beyond its core commercial property database, including a leasing comp database and a data analysis offering. The firm’s market value of more than $7 billion is 117 times greater than its estimated net income of $61 million in 2015 — a valuation that implies the expectation of strong growth to come.

Among its users, at least, CoStar’s rise has generally been viewed as creating efficiency as well as democratizing access. Commercial real estate data, once the purview of the well-connected few, is now available to anybody. “It makes the playing field kind of level,” said Stephen Shapiro, a senior vice president at JLL. The proliferation of data, he added, “helps everybody in the industry.”

That is, for those who can afford it. CoStar declined to comment on pricing, but a source said that an account with full access to CoStar’s national database can cost upwards of $70,000 per year.

The cast of true competitors is limited at best. Real Capital Analytics, (in which DMG Information, a subsidiary of the Daily Mail and General Trust, owns a minority stake) has successfully carved out a niche in investment sales data. Meanwhile, REIS, one of the handful of noteworthy public competitors, recorded $48 million in revenue in 2015, a fraction of CoStar’s $712 million. And startups like CompStak, RealMassive and Reonomy are looking to grow by using new technologies such as crowdsourcing to gather data.

Xceligent, a commercial listings database that was spun off from CoStar at the behest of regulators, has captured market share in certain secondary and tertiary markets, and is the only company seriously attempting to offer a product similar to CoStar, according to several sources. The company employs over 1,300 researchers, more than CoStar, which has 1,200 research staffers. But it is in far fewer markets and has yet to establish a foothold in New York.

With the exception of Xceligent, the main problem for competitors is matching CoStar’s prowess in collecting data. Florance claims that CoStar has the largest research team of any commercial real estate firm in the world, the product of $1 billion in investment.

“Nobody can wake up tomorrow and say, ‘I’ll have 1,200 researchers,’ ” said Richard Sarkis, co-founder of the rival commercial property information database Reonomy. “It is a huge barrier to entry right now.”

As a result, Sarkis said that the best startups can hope for is to carve out their niche around CoStar’s edges. “For me, it’s less about competing head-to-head, than to say, ‘What are different aspects of the work flow that are not being served by CoStar?’ ” he said.

Turf wars

If CoStar acquired its clout by thoughtfully amassing data, critics argue that it is holding on to it by bullying the competition. “Everyone is scared shitless of them,” said one source, who declined to speak on the record, citing fear of reprisal.

In 1999, the company filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against LoopNet, arguing that it should be liable for copyrighted CoStar images that allegedly landed on LoopNet’s database. Years of legal wrangling followed. LoopNet prevailed, but, according to one source, it was a “Pyrrhic victory.” “LoopNet expended a great deal of money, time and management resources on fighting CoStar,” the source said.

In 2014, CoStar filed a “John Doe” copyright infringement lawsuit against several unknown CompStak users. A federal judge subsequently issued an order forcing CompStak to hand over the names of the users in question. CoStar alleges that some users had uploaded its proprietary data onto the platform.

CompStak’s Mandel said there is “no doubt in [his] mind” that CoStar launched the suit simply to intimidate him. “It was all about scare tactics,” he said. He added that CoStar never contacted CompStak about the alleged infringement, and maintains that the data in question could have come from public sources. The charges against the CompStak users were dropped in June, just two months after it filed the suits.

Last year, CoStar launched a similar suit against Austin-based RealMassive, an online commercial real estate data marketplace, claiming the startup deliberately used property images from CoStar’s database. The parties settled in March, with RealMassive agreeing to pay CoStar $1 million. In a press release, RealMassive’s CEO, Craig Hancock, admitted that a few CoStar images ended up on its platform but insisted these were isolated mistakes. Hancock later argued that the amount RealMassive paid CoStar was less than it would have cost to defend the lawsuit.

Like Mandel, Hancock told TRD that he was never contacted by CoStar prior to the lawsuit. “Had they called us right off the bat, we would have removed the images,” he said. Referring to CompStak, Hancock added that given CoStar’s history, the lawsuit wasn’t “much of a surprise.”

In his statement to TRD, Florance addressed both the CompStak and RealMassive lawsuits. On CompStak, Florance said, “A federal judge in New York heard evidence that implicated CompStak users in stealing CoStar assets and compelled CompStak to disclose the names of those users. The information obtained by court order confirmed that theft had occurred, and CoStar settled the matter privately with the implicated parties.”

Mandel fired back, saying that theft by the users was never determined. “At the end of the day, Andy Florance feels threatened by a company that has managed to gather data that his company has failed to obtain for the past 30 years. It’s natural to be concerned about your competition, but for our part, we choose innovation over litigation,” he said.

Regarding RealMassive, Florance said that the company and its founder, Hancock, “systematically and intentionally designed a process to steal massive volumes of CoStar assets.”

Hancock responded by saying that CoStar’s claims of theft were “baseless,” adding, “While CoStar continues to aggressively smear competitors, RealMassive remains focused on innovating and collaborating with the industry.”

CoStar has also tangled with its subscribers. In December 2011, the company launched a PR war against CBRE after the brokerage’s head of capital markets, Christopher Ludeman, told his firm’s brokers not to share information with CoStar. In an interview with the Washington Post, Florance accused CBRE of trying to “corner” the data market to the detriment of the real estate industry. He called the brokerage business “the most concentrated industry that exists.”

Less than two years later, CoStar appeared to back off: It announced an exclusive agreement with CBRE that would allow its U.K. agents to use the database.

“There aren’t many companies with the testicular fortitude to [go after] their biggest customer,” said one leasing broker, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “[Florance] noticed that all these research teams were doing duplicative work. Now the industry is completely subservient to him.”

On the heels of monopoly complaints, the government has taken efforts to keep CoStar in check. In 2012, the Federal Trade Commission approved CoStar’s takeover of LoopNet under strict conditions: CoStar was forced to spin off Xceligent, the commercial property database similar to CoStar’s core product, and was barred from restricting its users’ access to Xceligent. The rationale was that by keeping Xceligent as an independent company, some level of competition would be preserved. CoStar could not block its users from passing data on to its competitors nor could it require them to buy any of its products as a condition for receiving additional services.

But despite the ruling, some observers worry that the company has too much pricing power. In late 2014, the company reportedly raised the cost of advertising properties on LoopNet as much as fivefold. “Get your checkbooks out and pay up! You have no other choice,” wrote commercial real estate blogger Duke Long at the time. “There is only one platform to market commercial real estate in the entire world. Better yet there is only one way to market property online.”

The threat of crowdsourcing

While CoStar bills itself as a tech company, the core of its business is still remarkably old-fashioned: researchers spend their days calling brokers, landlords and investors to get a hold of facts and figures that can’t be found in public databases. The firm claims to take a million photographs of properties each year.

“The real estate industry is still pretty heavily affected by asymmetric access to information,” said Edward Mui, an analyst at Morningstar who said CoStar is likely planning to consolidate its services to become the destination for all real estate data. “Access to data is still very valuable to investors, owners, operators and the like.”

But in contrast to CoStar’s painstaking data-collection methods, crowdsourcing, whereby brokers and landlords upload their own data online in exchange for the right to view others, is relatively easy — and costs virtually nothing. CompStak, for example, runs a crowdsourced leasing comp database that has won an ardent following. By all accounts, its database doesn’t have the same coverage as CoStar’s, but if it continues to grow, it could emerge as a viable and far cheaper alternative.

Florance recently acknowledged in a February earnings call that crowdsourced data can sometimes be more accurate than data gathered by CoStar’s research staff. He was referring to LoopNet, but the argument could be equally applicable to rivals like CompStak: Brokers who upload information on their own deals into a crowdsourcing database won’t necessarily produce less accurate data than researchers who call the same brokers and quiz them about their deals.

Chris Hagerup, an office leasing broker at EVO Real Estate Group and current client of CoStar’s who briefly worked for the company as a salesperson in 2012, said that despite its army of researchers, CoStar’s data is sometimes inaccurate or altogether lacking. “CoStar hasn’t gotten any better at getting good information,” he said. “They only added more sister companies to their portfolio.”

He argued that many real estate professionals have become accustomed to CoStar and may resist change, but as a younger generation moves up the career ladders, crowdsourcing could become more common. “It’s just weird to me that you still don’t self-input your information,” he said.

DMGI’s head of U.S. real estate products, Eric Frank, believes it is only a matter of time before his company’s firm Xceligent will match CoStar’s data offerings. “You have to have the commitment to catch up,” he said. A main advantage for Xceligent, according to Frank, is that many real estate professionals ache for a second player as an alternative to CoStar and are more likely to cooperate with the challenger.

“In any market where you don’t have a vibrant, competitive market, you’re not going to get the benefits that come out of competition,” Frank said. “Competition benefits the incumbent and the new guy, which should elevate everyone.”

But even if Xceligent and crowdsourcing startups like CompStak and RealMassive rise to become serious challengers to CoStar, the giant still has an ace up its sleeve: It could use its financial clout to buy startups and their technology, like it did with LoopNet -— a possibility that Andrew Florance recently alluded to.

“I’d have to say there’s more potential initiatives that we could pursue than I’ve ever seen before,” he said during the recent earnings call, speaking of possible takeovers. “We are looking at a lot of things.”

Correction: an earlier version of this post incorrectly claimed that DMG Information owns Real Capital Analytics. The company holds a minority stake.