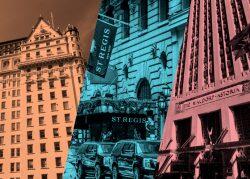

The DoubleTree Metropolitan is a quintessential Manhattan hotel.

Not a five-star, white-glove venue or hip party spot, but part of the lifeblood of the city’s hospitality industry — the big lodges with hundreds of rooms that cater to the masses of business travelers and tourists who visit each year.

While the vast majority of hotels are back up and running, the DoubleTree’s rooms are among thousands that remain stubbornly vacant at hotels that never reopened following the pandemic shutdown.

“There’s a huge financial storm hanging over most of these hotels,” said Vijay Dandapani, president of the Hotel Association of New York City. “If you’re a hotel that’s still closed, you need to have real compelling financial reasons.”

Two years after hotels began to turn their lights back on, 46 New York properties with more than 10,400 rooms remain closed, according to the hotel data company STR. That represents 8 percent of the city’s room inventory.

Read more

For comparison, 3 percent of hotel rooms in Orlando and Los Angeles are closed. In Miami and Chicago it’s 2 percent and 1 percent, respectively.

New York’s mothballed inventory persists despite a severance-pay law designed to force them to reopen, and high occupancy at the city’s open hotels — 86 percent for the four weeks ending Oct. 1, according to STR. It was 91 percent during the same period in 2019, before the pandemic.

Several factors explain the lingering closures. While leisure tourism has bounced back, business travel has yet to return to full strength. And while tourism shut down, hotel construction didn’t, adding supply to a struggling market.

New York hotel construction didn’t shut down with the pandemic. In the two years since 2020, the number of hotel rooms grew by 15 percent, according to STR.

“Part of this is about supply growth,” said Romy Bhojwani, director of hospitality market analytics at STR parent company CoStar Group.

Bhojwani said that if the 10,000-plus shuttered rooms were back online, the city’s occupancy figure would be a few points lower.

When the pandemic hit, New York was in the midst of a long, historic hotel development boom that had diluted the market with tens of thousands of new rooms. Tack on rising labor costs and higher property taxes, and many properties were already struggling even before Covid.

Some of the factors keeping hotels closed, however, are unique to each property.

At the moribund Four Seasons in Midtown, for example, billionaire owner Ty Warner is at odds with the hotel’s management company over operating costs and losses.

The Roosevelt Hotel has long been mired in an international dispute involving its owner, the Pakistani government, and an Australian mining company.

At other hotels, owners are coming to terms with a correction in values.

The Doubletree Metropolitan was finally unloaded in January by RLJ Lodging Trust for $146 million, a steep discount to the $332 million it had paid in 2010.

The buyer, Los Angeles-based investor Hawkins Way Capital, did not respond to requests for comment on its plans for the hotel.

Another large closed hotel, the Maxwell NYC, fell into foreclosure in September.

And the 655-key New York Marriott East Side has been snarled in litigation. The German lender DekaBank in 2016 sued its partner in its 2015 purchase of the hotel, Ashkenazy Acquisition, for allegedly reneging on a commitment to take over the property. DekaBank then filed to foreclose on Ashkenazy last year. A judge granted DekaBank summary judgment in August, allowing the case to move forward.

The three hotels were on a list of 10 closed properties that the City Council suggested this month could offer intake and relief services to asylum seekers.

At least one of the properties, though, is gearing up for regular customers.

The Hilton Times Square was purchased by Apollo Global Management and Newbond Holdings this summer for $85 million after the previous owner, California-based REIT Sunstone Hotel Investors, handed the keys back to a special servicer last year.

The hotel is set to reopen later this year.