For a few weeks in March, it seemed like 2008 all over again.

The tech industry’s go-to lender, Silicon Valley Bank, was seized. Depositors rushed to pull money out of Signature Bank, one of New York’s top multifamily lenders. First Republic, a major commercial real estate lender on the West Coast, was teetering on the brink.

New York City landlords were panicking. Another bank failure seemed imminent, and the survivors were bailing on real estate. The industry braced for a capital markets freeze like the one 15 years ago, which left stalled projects and developers scrambling for rescue financing.

Ira Robbins, though, seems unfazed. In late March, the 48-year old head of Valley Bank, a New Jersey-based lender with $57 billion in assets and overwhelming exposure to commercial real estate, sat in his immaculate office at One Penn Plaza with its panoramic views of the city and dished on the bank’s next moves.

Robbins had just made a bid to acquire Silicon Valley Bank’s assets from regulators. He said that in the past two weeks alone, it had opened more accounts than in an average quarter. Amid the broader retreat, this was his bank’s time to shine.

“As a regional bank CEO, I couldn’t be happier,” he said in an interview with The Real Deal.

Valley Bank has emerged as a key real estate lender at a time when other banks want nothing to do with the sector. It has carved out a niche lending to midsize landlords, including under-the-radar Hasidic dealmakers like Cheskie Weisz, but has also provided loans to more institutional players like Slate Property Group.

The bank was New York City’s 12th-largest real estate lender as of last summer, according to an analysis by TRD, issuing nearly $850 million across over 350 loans between July 2021 and July 2022. That placed it just behind Blackstone and just ahead of Signature Bank and Madison Realty Capital.

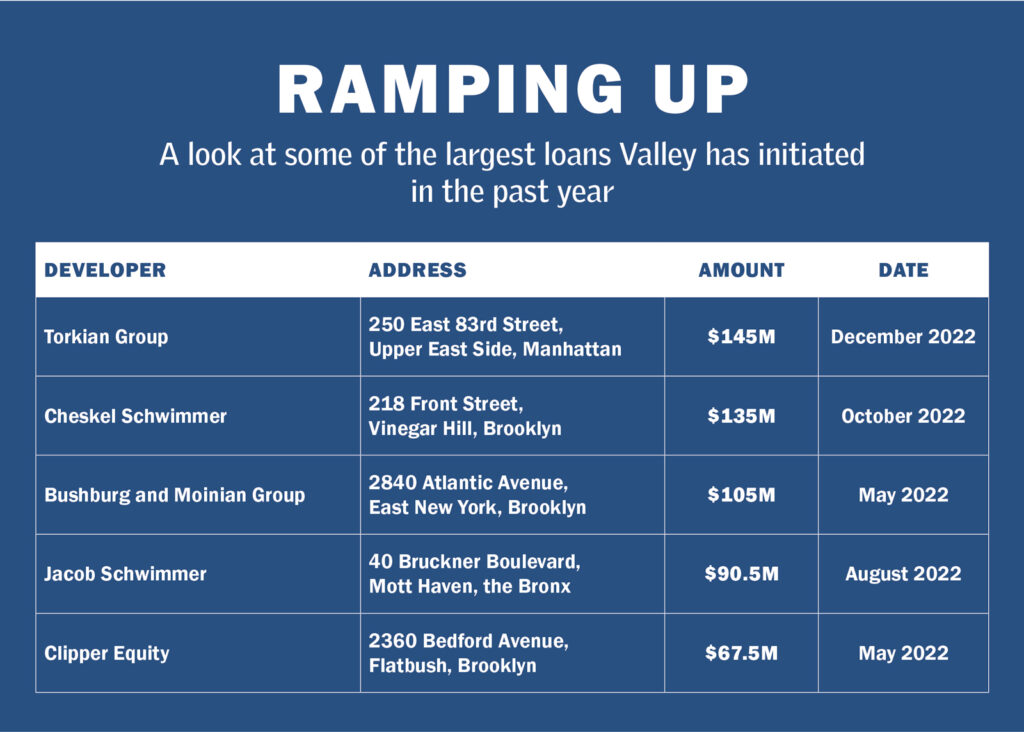

The bank has ramped up since then, funding a $145 million construction loan to Torkian Group for an Upper East Side apartment complex and a $135 million loan to jump-start Cheskel Schwimmer’s highly anticipated rental project near the Brooklyn Navy Yard in Vinegar Hill. It is also in talks to provide a much bigger construction loan in Brooklyn in coming weeks, according to a source familiar with the matter.

Valley is so exposed to real estate that S&P Global ranks it as the nation’s largest bank exceeding regulatory guidance on commercial real estate loan concentration. Its commercial real estate loan-to-capital ratio was 439.7 percent as of December, compared to the 300 percent threshold recommended by regulators.

Short sellers have taken notice: In mid-March, short interest on Valley’s stock was nearly double what it was a year before.

But Robbins is quick to dismiss these concerns. The bank has never posted a quarterly loss in nearly a century in business, he noted, and insisted that it has a diverse pool of borrowers, its office exposure is minimal, and it only lends at low leverage.

“Even if the valuation comes down 15, 20, 25 percent, the properties still [have] cash flows,” he said.

Keepin’ it local

Robbins is a true Jersey guy.

When he was on the job hunt as a senior in college, his mother sent him the Star-Ledger’s classified ads, with certain listings highlighted. One of her picks: Valley Bank.

“I came to find out later that my mom had no idea [whether] these were good companies or bad companies,” said Robbins. “As long as it was [within] a 10-mile radius, then it was a job that she circled.”

They are very smart about what markets they chose to be in.

He joined the bank in 1996 and rose through the ranks. In 2018, he became just its third CEO in more than 60 years.

The bank was founded in 1927 as the Passaic Park Trust Company. Gerald Lipkin, a former federal bank examiner, rose to CEO in 1989 and became the face of the bank, appearing in television commercials across the state. But it was Lipkin’s move into Florida that put the bank on the national map. In 2014, Valley acquired 1 United Bank, Palm Beach County’s largest lender, giving it access to South Florida’s wealthy deposit base.

It also gave Valley a first-mover advantage, years before affluent New Yorkers flocked en masse to a low-tax state during Covid. Florida now accounts for about a fourth of the Valley Bank’s business.

“They are very smart about what markets they chose to be in,” said Ken Thomas, a Miami-based banking analyst. “Miami is one of the top five markets in the country. And they became big here.”

Like his predecessor, Robbins made his mark with acquisitions. He targeted the U.S. arm of Israel’s largest bank, Bank Leumi, which was active in both New York and Miami real estate. The $1.2 billion deal, which closed last year, added about $8 billion worth of loans to Valley’s portfolio. And crucially, it allowed Valley to participate or quickly originate loans and sell them to outside investors in Israel, including to Bank Leumi in Israel.

Historically, most of Valley’s real estate loans were for under $5 million. After the Leumi acquisition, deals started crossing the $100 million threshold.

“I know when you look at Valley and there’s an article that comes across [that says] ‘Valley did a $100 million dollar deal,’” said Robbins. “But a lot of that credit risk would’ve been participated out. So that’s not what ultimately sits on our books.”

Robbins said the bank completed $1 billion in loans that were originated by Valley and sold to investors in Israel, which in banking is known as participation.

It frequently partners with Be-Aviv, a group with Israeli ties, on its deals, including a $36 million refinancing of Slate’s East Williamsburg rentals this year. In March, Be-Aviv and Israel’s Bank Leumi were involved in Valley Bank’s $50 million loan for Staten Island-based Tona Construction & Management’s first New Jersey project: a 200-unit rental building in Newark.

Tona’s Frank Tonacchio said that Be-Aviv and Bank Leumi’s involvement meant the deal took longer to get done. It also was more costly than a traditional senior loan, because Be-Aviv’s piece was blended with a mezzanine loan.

“It’s higher than any loan that we’ve taken,” said Tonacchio, who noted that the interest rate is close to 12 percent and the loan required personal guarantees.

But Tonacchio added that it’s a difficult time to get construction financing, and Tona’s project did not get much interest from traditional banks.

The Bank Leumi deal gave Valley the juice to make bigger loans, but it also exposed it to some high-risk deals. In 2016, Bank Leumi became the senior lender on Fortis Property Group’s condo tower at 161 Maiden Lane in the Financial District, which has become a major boondoggle. The unfinished project is now at the center of lawsuits between Fortis, its lenders and its general contractor amid claims that the building leans slightly to the north.

Robbins said he is not aware of the status of 161 Maiden, but Valley had marked it to zero when it acquired Bank Leumi.

The other Valley Bank

As the banking crisis played out in March, Valley came close to another acquisition even bigger than Bank Leumi USA. It emerged as a bidder for the assets of Silicon Valley Bank after its seizure by regulators, but ended up losing to North Carolina-based First Citizens.

“There were some very profitable businesses, and from an organization like us, it would’ve continued to diversify our balance sheet,” Robbins said of the proposed takeover.

Thomas, the banking analyst, said the fact that regulators even allowed Valley the chance to acquire Silicon Valley Bank suggests it sees the bank as being on solid footing.

“That says a lot about the strength of the bank and how the regulators think of them,” said Thomas.

When asked about Signature’s loans, Robbins had a quick response: Not interested.

“I think as we looked about Silicon Valley, those were new relationships that we could have gotten into,” said Robbins. “Most of the Signature clients are people we could have banked already.”

The fallout could still lead to more opportunities for Valley, a matter on which Robbins gets philosophical. There are only so many banks that provide loans to the smaller landlords, he noted. With higher interest rates and Signature out of the picture, who is going to step in?

“There’s less competition in our space today and there’s more demand for the types of loans that we offer today, so I’m ecstatic for me,” said Robbins. “From an industry perspective [though], I think it’s a problem.”

Still, Robbins — like everyone in New York’s banking sector — is closely watching the upcoming sale of Signature’s $60 billion loan book this summer.

“Signature’s failure is going to impact pricing and appraisal values quicker than we’ve historically seen through any cycle,” he said. “We haven’t, I don’t think, mentally adjusted for that.”