In 2022, Dara Ladjevardian co-founded artificial intelligence digital clone firm Delphi in Miami, joining a wave of tech entrepreneurs moving to the city.

“Miami was an incredible launchpad for Delphi — vibrant energy, a melting pot of cultures and a growing tech scene,” Ladjevardian’s digital clone (don’t ask) told The Real Deal.

From late 2020 through 2022, venture capitalists, software engineers and others in tech descended on Miami, feeling the pull of its vibes, eagerness to receive the transplants and early lifting of the pandemic lockdown, especially after Mayor Francis Suarez posted on X, in response to a venture capitalist’s suggestion of moving California’s tech hub to Miami, “How can I help?” Some soon coined the Magic City “Silicon Valley of the South.”

Fanfare over the sector’s new local offices accompanied the swift rebranding. Headlines blasted each new lease, fueling the real estate industry’s giddyness and bolstering its argument that techies were building a healthy South Florida office market at a time when practically every other downtown in the U.S. struggled due to remote work.

Today, Ladjevardian’s Delphi is based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

He wasn’t the only one to make the round trip.

Over the past two years, many rank-and-file techies got called back to their offices. Others, including founders like Ladjevardian, voluntarily returned to the Bay Area, the center of the action for AI.

“As we scaled, San Francisco’s ecosystem offered unmatched resources and talent density,” Ladjevardian said. “It’s like moving from a promising startup to the epicenter of innovation.”

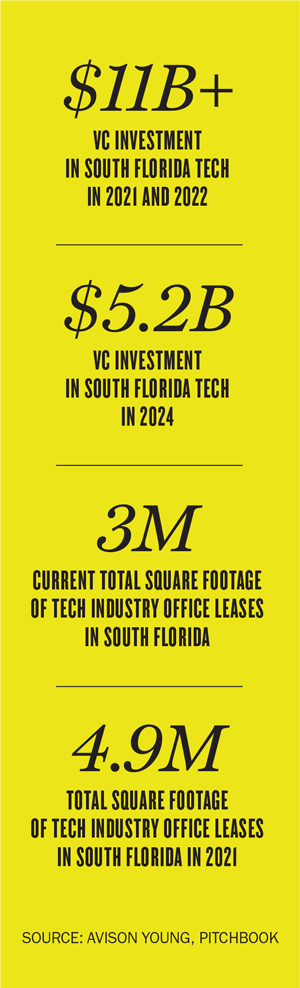

The departures punched holes in the bubble, and the once-exuberant tech offices shrank, literally. The industry now occupies 3 million square feet in South Florida, down from 4.9 million square feet in 2021, according to Avison Young. Even during the 2021 and 2022 hype years, data show, tech leasing didn’t represent a sizable portion of office deals.

“It’s like moving from a promising startup to the epicenter of innovation.”

“We tend to get ahead of ourselves here,” Peter Zalewski, a longtime South Florida real estate market analyst, said. “What we always do as a community [is] get behind a fad, talk about how it is going to change our community and lifestyle. … There’s always a lot of hype, a lot of pizzazz, a lot of promises of jobs and economic development. It’s just a fad. It’s always just a fad.”

Case in point: In 2021, when much of the South Florida tech excitement was over cryptocurrency, digital currency exchange FTX branded the Miami Heat arena, its name painted on the basketball court’s floor. After the spectacular FTX implosion, the arena was quickly rebranded to Kaseya, a cybersecurity and IT management software firm powered by AI, the new “it” tech field.

On AI, Miami couldn’t keep up. “San Francisco is the beating heart of AI,” Angela Hoover said in 2023 when she moved her AI chatbot firm Andi to the Bay Area from Miami, according to an NBC report. Major tech investor Andreessen Horowitz bowed out of its Miami Beach lease last year, while expanding its Menlo Park office. Others that opted out of South Florida offices include venture firm Plug and Play and crypto exchange Blockchain.com.

Yet the mania hasn’t completely fizzled. Boosters say the techpreneurs who remain are serious about South Florida and that the boom wasn’t just theory. The staying power is supported by several new leases, including by Spotify, Sony and Amazon in Wynwood, and Apple in Coral Gables, and by a Steve Ross bid to bring a Vanderbilt University campus and innovation center to West Palm Beach.

“To state that tech is dead in Miami is absolutely ridiculous,” said Jeff Ransdell, founding partner at Fuel Venture Capital, a local tech investor. “I don’t have five minutes seven days a week.”

By the numbers

Tech companies need money before they sign leases, and for several years, they had a lot of it.

When nationwide venture capital investment reached its record in 2021, South Florida also hit its apex, scoring major funding for local startups.

Global investment in South Florida tech was $11.1 billion and $11.4 billion in 2021 and 2022, respectively, a far cry from the San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont metropolitan statistical area’s $127 billion in 2021 and $74.3 billion in 2022, according to data from PitchBook.

After a bear market took hold sometime in late 2022 amid elevated interest rates, continued inflation and lower valuations, investment slowed. (Though some regions have by now experienced an uptick in funding, a recovery is yet to manifest in South Florida.)

In the San Francisco metropolitan area, investment dropped to $53.2 billion in 2023 before increasing to $86.6 billion last year, which outpaced the pre-pandemic years of 2018 and 2019.

By contrast, in South Florida, venture capital funding was $5.2 billion last year, less than the $6.1 billion in 2019 but still more than 2018’s $4.4 billion.

“It’s hard to make the argument that we are really competing on the tech side,” Juan Arias, South Florida market analytics director at CoStar Group, said.

South Florida tech office leasing has declined in tandem. New deals and renewals for industry tenants were nearly 277,500 square feet in the tri-county region in 2021, dropping almost 40 percent to 170,500 square feet last year, Colliers data shows.

Even during the buzziest moments, tech didn’t play as major a role in the tri-county region’s market as was hyped, data now show. The industry represented 8.8 percent of all leases in the tri-county region in 2018 and 11.6 percent in 2019 but dropped to 10.7 percent in 2021, 7.5 percent in 2022, 7.8 percent in 2023 and 5.7 percent last year, according to data from CompStak, whose data is based on deals reported to its database. That’s nowhere near tech leasing in the Bay Area, where industry firms represented between 31 and 52 percent of all office leases in each of the past six years.

The missing AI explosion explains the fate of tech in Miami, compared to its would-be peers.

In the region, venture capital investment in AI and machine learning companies went from $2 billion in 2021 to $2.6 billion in 2022, before decreasing to $550 million in 2023 and $1.6 billion last year, according to PitchBook.

In the San Francisco metro area, not only were the investment dollars multiples higher, but they also continued to grow after 2022. Venture capitalists put $42.8 billion into Bay Area AI firms in 2021, $24.4 billion in 2022, $33.1 billion in 2023 and $61.6 billion last year. So far this year, they’ve already invested $4.3 billion in the San Francisco metro area but only $460 million in South Florida, PitchBook data shows.

As a result, office leases by AI companies barely made a dent in the South Florida market, representing just 0.12 percent of all leases in 2021, a sliver of their 2.7 percent in the Bay Area that year. In 2024, South Florida AI companies were 0.11 percent of leases, while in the Bay Area they accounted for 7.9 percent for the year, according to CompStak.

“AI needs a lot of money. … It’s a little bit tougher to say, ‘Hey, we are going to get an in-migration of AI companies here,’” Arias said of South Florida. “Why? There are a couple of things. [One is] the access to talent that really we don’t have yet. It’s one of the major problems the business community continues to express.”

Patrick Murphy, CEO of Miami-based Togal.AI, knows the problem well. The company was started in 2019 within the Murphy family’s general-contracting firm Coastal Construction, also based in Miami. Togal, which automates estimates for windows, electrical sockets and other fixtures for projects, searched for tech talent in South Florida.

“It either wasn’t affordable, but really — honestly — not available,” Murphy said. “Very few of those folks live in South Florida, especially the AI and Ph.D.-level mathematicians. They are not churning out of local education institutions like they are in other parts of the country or world.”

Across tech sectors, South Florida’s talent pool of 80,650 workers in 2023 represented 2.8 percent of its total employment; the sector grew by nearly 9,870 new jobs since 2018, according to CBRE’s Scoring Tech Talent 2024 report. From 2018 to 2022, 14,969 tech degrees were earned across the tri-county region, outpacing the jobs added.

That means some of the tech workforce may have to move to other markets to find jobs. They might look to the cities where tech ecosystems are more robust than the tri-county’s: San Francisco, New York, Toronto, Dallas-Fort Worth and Seattle.

No Bay Area dreams

Those still long on Miami tech say the city will build in its own way and that comparisons to other hubs aren’t useful.

“It’s like someone from Silicon Valley trying to compete with us on condo[s],” Zalewski said.

Even Andreessen Horowitz, the California-based VC that canceled its Miami Beach lease with three years left on the term, still has staff here — they’re just working remotely, according to Ransdell.

Miami-based Kaseya never had issues finding talent in the city, with many of its top executives being local hires, Xavier Gonzalez, chief communications officer, said.

Not every worker at Kaseya is an engineer. Out of its roughly 1,500-person workforce in Miami, 55 percent are in sales and marketing, while 18 percent are corporate and 27 percent are tech staff, according to Kaseya data. That’s enough staff to occupy 245,300 square feet in four offices in downtown Miami and Brickell.

Kaseya went against the grain, leaving Silicon Valley, where it was founded in 2000, opening a Miami office in 2015 and moving its headquarters to the city in 2018. At the time, South Florida was experiencing the first signs of a push into tech, with eMerge Americas, a firm that connects investors with companies, gaining steam. Kaseya seized on this.

“We were ahead of that curve and knew of the powerful potential of Miami as a tech hub,” Gonzalez said.

“To state that tech is dead in Miami is absolutely ridiculous. I don’t have five minutes seven days a week.”

Much of South Florida’s “older” tech companies are built on top of a local strength: health care.

Medical technology and medical-device tech companies are longtime “Silicon Valley of the South” bulwarks, according to Kelly Smallridge, CEO of the Palm Beach County Business Development Board.

This niche needs space.

Modernizing Medicine, a cloud-based electronic medical records tech firm founded in 2010, originally had offices in Boynton Beach and Florida Atlantic University’s Research Park, before moving to a 100,000-square-foot headquarters in Boca Raton in 2019. In 2018, medtech firm Stryker’s Mako Education Center opened a 40,000-square-foot facility in Fort Lauderdale to train doctors in robotic-assisted surgery; it also runs a Robotics Innovation Center in Weston.

Miami-based Fuel, the VC firm, has a deep portfolio from both before and after the frothy 2021-2022 period. It backed boat-sharing company Boatsetter in 2019; Taxfyle, a real-time app connecting customers and tax professionals, in 2017; fintech and AI firm Leap Financial and voice AI firm Ybot last year. Its thesis includes AI companies and tech firms that capitalize on the region’s proximity to Latin America.

Last year, Miami ranked 16th in the Global Startup Ecosystem Report, posting a $94.4 billion ecosystem value of its startups valuations and deal exits from 2021 to 2023.

“It’s steady, healthy, thriving — not flashy,” Tatiana Silva of the Miami-Dade Beacon Council said.

West Palm in the mix

Two years into the tech slowdown, a reference to South Florida as the next Silicon Valley resurfaced.

Billionaire Steve Ross said he had plans to turn West Palm Beach into “Wall Street South” by tenanting his new office towers with financial service firms.

As he works to reshape the city, he has also set his sights on bringing in tech firms.

“We are actively working to attract technology firms to West Palm Beach, with the aim of transforming it into the next Silicon Valley,” Jordan Rathlev, senior vice president at Related Ross, said. The firm “is noticing a shift as technology companies look into the area,” he said.

Much of the tech plan in West Palm is rooted in the planned Vanderbilt University campus in the city, which Ross fundraised and advocated for. It will include data science and AI programs, as well as an innovation center connecting startups, academia, investors and existing companies. Nearby Palm Beach is a residential cluster of millionaires and billionaires, the perfect audience for techpreneurs looking to pitch and raise funding.

And perhaps it does take a developer to make a city into a tech hub.

“The work Steve Ross is doing has more strength behind it than whatever a mayor does on Twitter, Arias, the CoStar analyst, said. “They have deep contacts, they have the money. It is a little bit faster than what the government can do.”

“By a little bit, I mean a lot,” he added.