Dorothy Parker is often misquoted as calling L.A. “72 suburbs in search of a city.”

The famous satirist probably didn’t say that, but whoever did had a point that stands 100 years after Parker supposedly said it — L.A. is unlike almost any other global city due to its sprawl.

“The biggest problem L.A. has is its lack of a center” said John Eichler, a Cushman & Wakefield broker who specializes in Downtown L.A. “And [that] identity makes it a lot more confusing for institutional investors.”

Regardless of what money they actually spend here, investors will certainly tell you they’ve got their sights set on Los Angeles. The metro area has topped CBRE’s Americas Investors Intention Survey each year since 2016, and it’s easy to see why.

L.A. is the only other U.S. metro area besides New York that produces an annual gross domestic product above $1 trillion. GDP per capita growth in L.A. from 2013 to 2018 was twice that of the rest of the country and three times that of New York over the same period.

It’s the third largest real estate market in the world with an estimated value of $482 billion, behind only New York and Tokyo, according to CBRE.

And yet a closer look at some key rubrics make L.A. look more like a second-tier city. If, for example, you look at office rents, the space in Downtown L.A. is priced closer to rates in downtown Houston than New York or San Francisco.

And Class A space in L.A.’s most expensive submarket, the Westside, rents for less than any submarket in all of Manhattan besides a chunk on the east side of the Financial District.

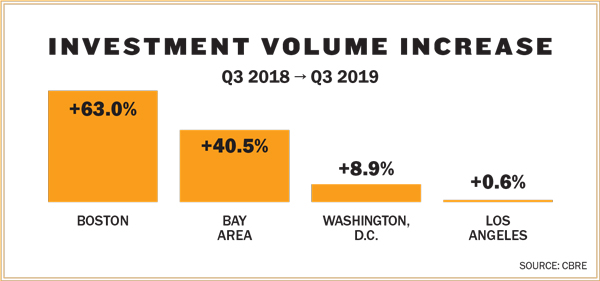

In terms of overall commercial investment volume, L.A. has consistently seen the second-highest number of dollars invested behind New York, but it doesn’t post the kind of growth other top U.S. markets do, like the Bay Area, Washington or Boston.

Investment volume in L.A. grew just 0.6 percent in the year ending in the third quarter of 2019. Boston saw investment volume grow 63.2 percent over that time. The Bay Area saw 40.5 percent growth, and Washington, D.C., saw 8.9 percent growth.

The numbers suggest investors should be pouring into L.A., so what gives? Simply put, L.A. is a tough market to crack, especially for outside institutional investors who don’t know the neighborhoods.

“As to whether L.A. is undervalued, with L.A. you have to ask a different question: What submarket in L.A. may be undervalued and overvalued?” Eichler said.

“The market dynamics in Downtown L.A. and Santa Monica, only 10 miles apart, are just as disparate as those fundamentals between Downtown L.A. and Seattle and New York.”

The home-team advantage

L.A.’s idiosyncrasies give locally based firms an edge over national firms, and the latter often partner with local outfits to tap into that market knowledge.

But it can be a struggle to find opportunities in the L.A. metro area. The high costs of land and costs associated with lengthy entitlement and environmental approvals in California discourage development in many parts of the metro area.

“You have to comb through a lot of opportunities to find those situations that underwrite from an investment perspective,” said Robin Potts, director of acquisitions at Century City-based investment management firm Canyon Partners. “The barriers to entry for development limit opportunities in terms of being able to create those assets that core buyers are looking for.”

To be sure, the submarkets that can sustain rents needed to make a new institutional-grade project pencil out are seeing plenty of activity, as well as growing rents.

The emerging tech-entertainment hybrid industry in Silicon Beach neighborhoods like Santa Monica, Culver City and Venice is fueling high-value projects and deals across property types. Tech companies signed 1.6 million square feet of office leases in the first three quarters of 2019, according to Cushman & Wakefield.

Canyon, for one, is developing the $350 million Ivy Station mixed-use project in Culver City in partnership with AECOM Capital, Lowe and Rockwood. HBO leased all of the 240,000 square feet of office space at Ivy Station in April.

L.A.-based firms, including Hudson Pacific Properties, Hackman Capital and Kilroy Realty Corporation, are the most active in Silicon Beach.

But domestic investors from outside L.A. have also fared well with their Silicon Beach projects. In August, Dallas-based Lincoln Property Company signed Universal Music Group to a lease at its Colorado Campus in Santa Monica worth a reported $6.20 per square foot, around 10 percent higher than the average across the Westside.

Foreign investors have barely penetrated in Silicon Beach but have stepped up activity in the red-hot industrial sector. Total foreign investment in L.A.-area industrial properties nearly tripled in 2018. Seventy percent of the $910 million in foreign capital invested in industrial came from China and Canada, according to CBRE.

Other demand from abroad appears to be there, though. Despite a drop in investment from China — by far the largest source of international capital in L.A. — around 20 percent of international investors surveyed by the Association for International Real Estate Investors last spring said they wanted to increase exposure to the L.A. market, compared to just 9 percent who want to decrease exposure.

Global competition

It’s hard to say if institutional investors will be able to build a bigger presence in the area given the short supply of viable investments, but generally it appears demand will remain strong in the near future. L.A. is one of a handful of global cities that still have room to grow and where investors are betting on growth.

“Of all of the big global gateway markets, Southern California and L.A. have further to run because they got going a bit later than the other gateway markets,” said Richard Barkham, CBRE’s global chief economist.

Commercial property prices in L.A. grew 10.1 percent year-over-year in the third quarter of 2019, the sixth-strongest growth among 18 global cities tracked by Real Capital Analytics in its Global Cities Composite Index, trailing only Boston, Toronto and San Francisco among North American cities.

Conversely, demand appears to be slowing in other top-tier markets — prices fell in Chicago, Manhattan, Paris, Washington and Singapore during that period.

L.A. beats out most institutional-grade cities outside the U.S. on a cap rate basis, although competition is stiffer stateside.

“On a global comparison, it’s good value,” Barkham said. “On U.S. comparison, it’s not out of line: It’s not good value, it’s not bad value. I’d say it’s fair value.”