Ask a toddler to draw picture of a beach, and it would probably look like the one in Fort Lauderdale. The sand is white and the water is blue. The palm trees offer sparse shade.

On a March day, spring breakers sprawl across the sand. They’re young and sunburned, and they flock to the strip lined with spring break spots: the Elbow Room, Señor Frog’s and the Drunken Taco. Locals are probably on the water. There are 100 marinas and 50,000 yachts registered in Fort Lauderdale, a city of 184,000 people.

Nine miles up Route A1A, families prefer the pier in Pompano Beach. They lounge on the beach and get lunch at spots such as Burgerfi and Lucky Fish. The landscaping is lush and the energy is mellow. It’s nothing fancy, but it’s nice. But change is coming. The signs are there, advertising sales galleries for luxury condos with such brands as the Ritz-Carlton, Armani and Waldorf Astoria.

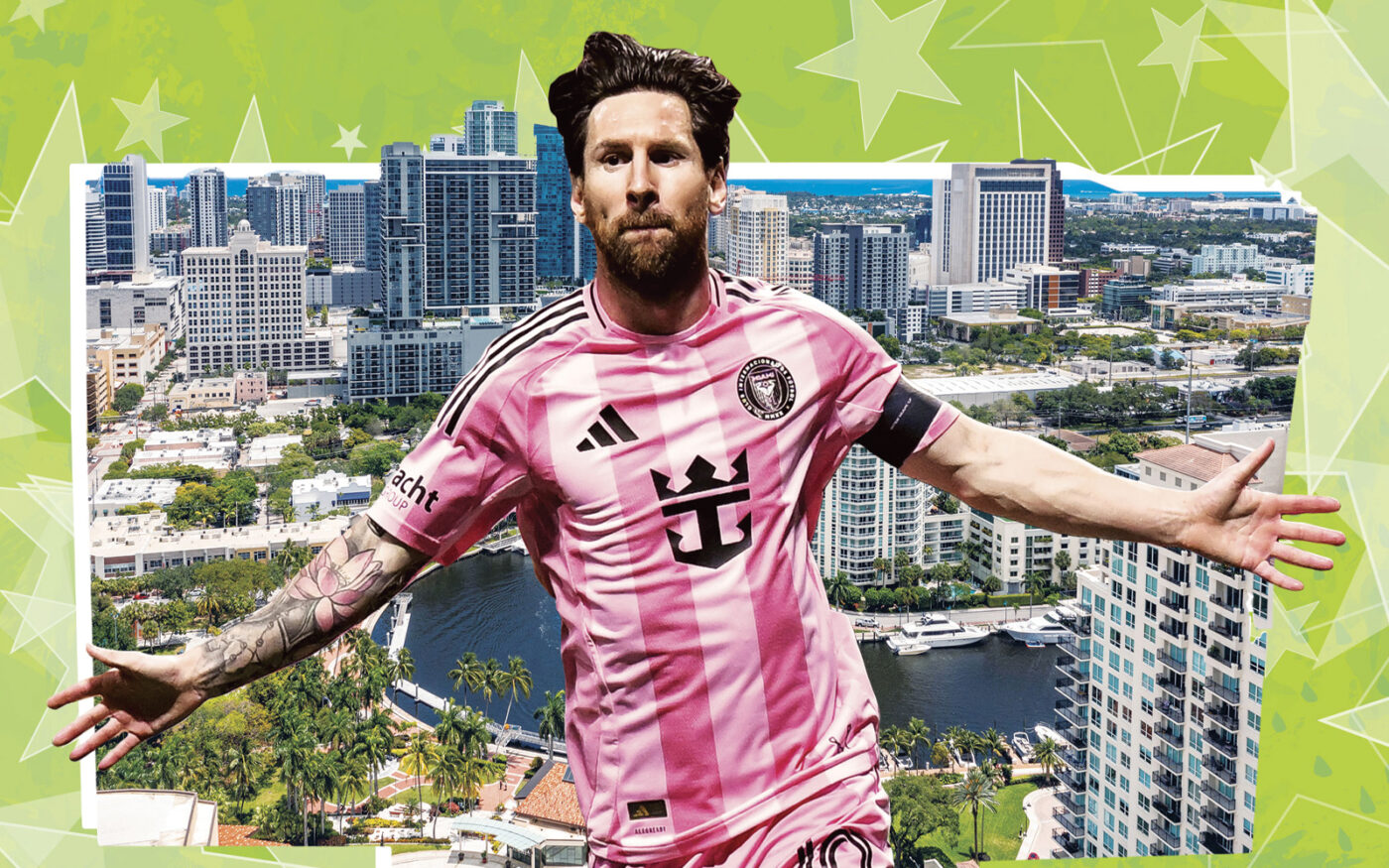

Inland, in the rural enclave Southwest Ranches, Gisele Bündchen picked up a $9 million dollar equestrian estate. Soccer megastar Lionel Messi brought the global spotlight in 2023, when he bought an $11 million waterfront mansion in Fort Lauderdale’s gated Bay Colony neighborhood as part of his move to Inter Miami.

That Broward County could be home to two of the most famous people in the world would have been unthinkable five years ago.

Straddled by Miami-Dade County to the south and Palm Beach County to the north, Broward is South Florida’s forgotten middle child, for decades upstaged by its more expensive, higher-profile neighbors.

“Fort Lauderdale, the lifestyle is a little more at ease,” Related Group’s Nick Pérez said. Related, with Merrimac Ventures, is behind the Waldorf.

But Broward’s moment has finally arrived. There are over 3,900 condo units across more than two dozen projects in development, according to an analysis by The Real Deal, and they’re being built by the region’s big names: Related’s Pérez family, Isaac Toledano’s BH Group, Miki Naftali’s Naftali Group and Edgardo Defortuna’s Fortune International Group — which, with Oak Capital, is behind the Ritz-Carlton — all have projects here. Even the Rabsky Group, known for redeveloping Brooklyn, has approvals to build three towers in Fort Lauderdale. Related in particular is betting big on Broward, with seven condo projects stretching from Hollywood to Hillsboro Beach.

Brickell and West Palm Beach are buzzier, better-known centers of South Florida’s real estate boom, but Fort Lauderdale and Pompano Beach have caught the attention of developers, who pitch the county as a more affordable, relaxed alternative to Miami-Dade for local and out-of-state buyers alike. There’s room to grow, especially with hospitality brands that can elevate the area with luxury buyers.

The shift goes beyond the luxury new development market. For decades, even Broward’s most upscale neighborhoods have lagged in pricing compared to their Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counterparts. While deals over $50 million take place on a semi-regular basis in those other markets, Broward has seen only one deal at the trophy price point: financier Donald Sussman’s record $70 million sale last September. Before that, Broward’s record was a $40 million deal in 2023, and before that, it was a $32.5 million deal in 2022. The price records in Palm Beach and Miami-Dade counties, meanwhile, both top $100 million.

With the herd of South Florida developers moving to Broward, billions of dollars are on the line, dependent upon thousands of units selling to luxury buyers, many of whom could afford to buy in Miami or West Palm Beach. So much development and wealth could change a place known for its mass market appeal and party spots.

Apples and oranges

Developers and agents say Broward’s growth wouldn’t be possible without the pandemic catalyzing the market — and saturating Miami’s. Many of Broward’s buyers are Miami price refugees, fleeing the global megawealth warping the city’s cost of living.

“People who are looking for second homes or to invest in real estate also have budgets,” Pérez said. “As people get priced out of Miami, they’re looking at other options.”

Most of the buyers come from the Northeast, the Midwest and California, brokers and developers say. The biggest difference for developers, who are accustomed to building and selling in Miami, is the lack of Latin American buyers.

Broward’s biggest international demographic is Canadian second-home owners, as made evident by all the Quebec license plates parked along Pompano Beach.

Agents said that selling these projects to mostly domestic buyers is different. The buyers are willing to spend more, but they’re accustomed to mortgages and can be uncomfortable with deposit structures.

“You can’t replace beach. It’s our best asset.”

“Everything is different, the buyer pool, the process,” Ryan Shear, a principal with PMG, said.

Land here is cheaper, and the playing field for projects isn’t as crowded. In Miami-Dade, developers can struggle to find sites at prices that make a project feasible, he said.

“You can still find empty lots in Broward,” said Fernando de Nuñez y Lugones, CEO of Vertical Developments, which along with its partners is planning the 28-unit Armani/Casa Residences Pompano Beach and the 36-unit Riva Residenze condos in Fort Lauderdale.

Prices for those lots are cheaper than equivalent sites in Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counties. Vertical and its partners paid just $8 million for the 0.8-acre Riva Residenze in 2022. In 2020, Fortune International Group and Oak Capital paid $27.5 million for the 4.6-acre oceanfront site for the planned Ritz-Carlton Residences, Pompano Beach.

“You can’t replace beach. It’s our best asset,” said Pérez, who conceded that the beaches in Fort Lauderdale and Pompano Beach are even better than many of Miami’s.

“When you look at Fort Lauderdale, it’s not like Miami,” Naftali, who is planning the 45-story, 370-unit Viceroy Residences Fort Lauderdale, said. “It has a lot to offer and compete with major cities around the world.”

But why does everyone suddenly want to build a condo tower here? Broward has for so long been derided as the source of so many only-in-Florida scandals: Bribery, incompetence and dysfunction are repeated themes.

“I wish I could give you an intelligent answer to that,” Shear said. “To be honest, I didn’t know Fort Lauderdale or Broward that well five, 10 years ago.”

He’s now planning the 28-story, 44-unit Sage Intracoastal Residences Fort Lauderdale, an idea Shear says he got from watching his fellow developers.

“We saw other developers be successful selling condos,” he said. “So we wanted to join the party.”

How it started

The party was largely started by the Pérezes and Defortuna, who were partners in the Auberge Beach Residences & Spa Fort Lauderdale, a 171-unit oceanfront project that set price records for Broward when it was completed in early 2019. The success of the Auberge was followed by Fort Partners and Merrimac Ventures’ Four Seasons Residences Fort Lauderdale, an oceanfront complex with 83 condos and 148 hotel rooms that sold out for an estimated $350 million.

The Auberge and Four Seasons are just north of the planned St. Regis Resort and Residences, Bahia Mar Fort Lauderdale, a redevelopment of 40 oceanfront acres and the current site of the Bahia Mar Yachting Center, which hosts the Fort Lauderdale International Boat Show each year.

The project has been in the works for more than a decade, stalled by disagreements between the city, the boat show and the developers, Jimmy Tate and Sergio Rok, who eventually brought in Related as a partner on the resort.

The first phase of the St. Regis Bahia Mar will cost an estimated $2 billion. It includes two 23-story condo towers, a 197-key luxury hotel and a private beach club. Douglas Elliman’s Daniel Teixeira, who is leading sales at the project, described his buyers as affluent individuals looking for “a marina lifestyle.”

“When you think of Fort Lauderdale, you’re no longer going to think of spring break,” Pérez said. “You’re going to think of a world-class yachting destination.”

The city is looking to align itself with loftier figures than drunk, sun-starved college kids. In 2022, Fort Lauderdale invited Prince Albert II and Princess Charlene of Monaco to attend the grand opening of the city’s aquatic center — and they came. Their January 2023 visit was part of a broader effort to build a relationship between the two yachting hubs.

But a luxury shift requires more than a royal friendship, and Fort Lauderdale is not yet a peer to Monaco. Even if all these developers pull off their projects, success could pose tough questions for local leaders who already need to solve the problems of crippling traffic and an affordability crisis.

“Real estate is like a nuclear bomb,” de Nuñez y Lugones said, moving his hands to mimic a blast radius. He sees the development process unfolding as “a mega gentrification” of the region.

“The local people who have been here are pushed to the west,” he continued. “And you’re going to have the wealthiest people in the world having a first or second home towards the water.”

That’s if everything goes to plan. And developers say they’re not there yet.

“What is missing here is quality,” Naftali said bluntly. “When you start to see demand for true quality, you see customers that are asking for great restaurants, really quality condominium buildings and quality of lifestyle — that’s changing the city.”