Nir Meir hoped Miami would be a new start.

In 2021, the former HFZ executive dropped nearly $2 million to rent a seven-bedroom estate on the beach. He spent time there and at ZZ’s, a high-end, members-only social club.

He was seen out everywhere. He’d party one night at a full-nude strip club in Miami, and hand out drinks the next at upscale restaurant Casa Tua. He’d fly to New York on a private jet, drop thousands of dollars at Daniel and crash at the Mark. He owned Porsches, an Aston Martin and multiple Mercedes. One month, he spent over $200,000 on wine.

Behind the scenes, Meir’s life was in chaos. His eventual fall ravaged HFZ, the firm he’d helped build into a high-profile luxury developer.

Embellishing the truth is second nature to many real estate developers. Meir went beyond. He allegedly lied about his boss having heart surgery and had someone fake a Korean accent to dupe investors. He allegedly forged wire transfers and stole a house.

Those who have worked with Meir have called him a bully, but he could also be a best friend, a confidant, even a mentor. He lied to the press, even once duping this cynical, ink-stained reporter who’s covered fraud for years. He’d be charming, seductive. Whatever you wanted out of life, Meir could provide.

The story of Meir’s fall from grace is so wild, it’s reached outside the industry grapevine. Within the real estate world, it’s become a morbid fascination for many — you think he couldn’t fall any further or lie any harder, and then he does. He’s now behind bars at Rikers Island, awaiting trial for allegedly masterminding a multiyear, $86 million fraud. The charges include grand larceny, tax fraud, falsifying business records and money laundering. Yet until the law caught up with him in February, you still might have run into him at Carbone.

One source called Meir real estate’s Rasputin. He came out of nowhere and rose through the ranks, promising cures but providing poison. He seemed unkillable, surviving attempts to take him down while maintaining the capacity to topple a multibillion-dollar company, his partner, his contractors and his wife. He ultimately did: HFZ lost its flagship condo development on the High Line, the XI, in the biggest developer implosion of the Covid era. But Meir’s story isn’t as simple as a rise and a fall. Power, for Meir, was not putting up a shiny condo. His dream was never to be told no.

“We used to joke, a loan is due and Nir would jump on the next plane and come back with a bag full of money.”

Even at his first criminal court appearance recently, Meir lied. Hunched over, with dark bags under his eyes, he told a judge he was the sole provider for his family. Weeks earlier he had filed for bankruptcy, claiming $50 to his name and no source of income.

In real estate, developers boom and bust, stretch the truth and move money from project to project, aiming to eventually pay back investors and banks. Sometimes they get stuck mid-maneuver.

For Meir, though, the game went well beyond that. Those caught in his web are now trying to understand how he played it, and why.

At home in real estate

Meir was born in Israel in 1975. No one seems to know exactly where.

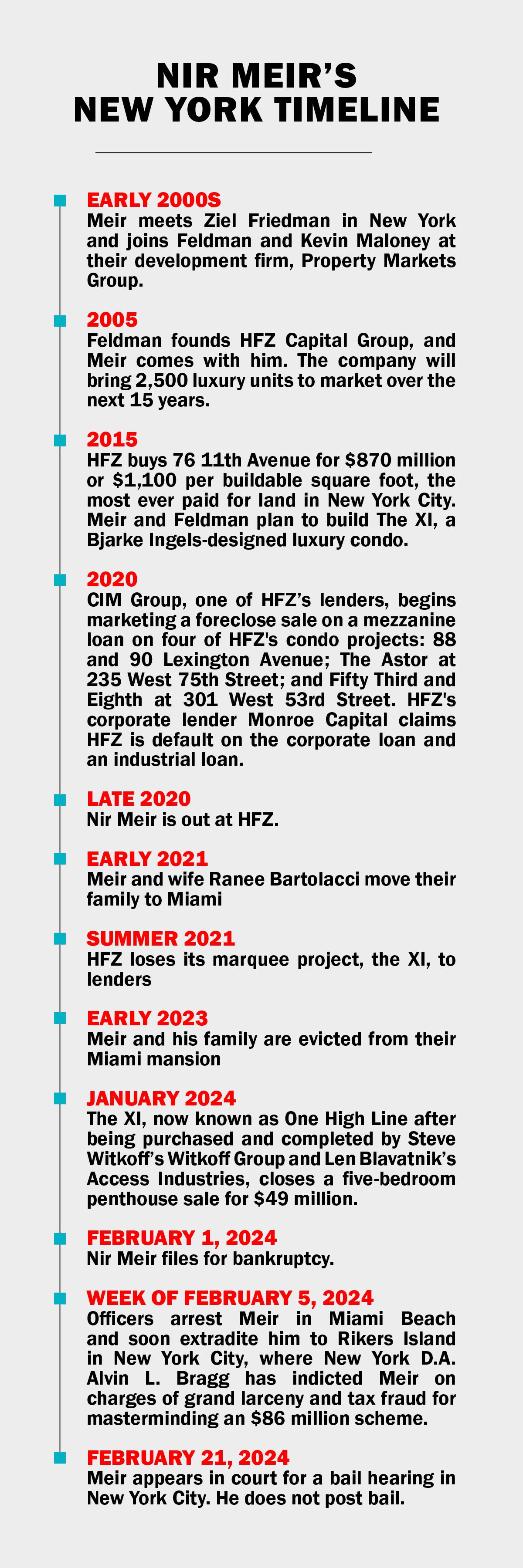

He has said he went to college in France, dropped out, moved to the U.S. and became a broker. Meir was leasing apartments to corporate tenants in Manhattan when he met Ziel Feldman around 2003 and latched on. Meir joined Feldman and Kevin Maloney’s New York development firm, Property Markets Group.

In 2006, Feldman was an investor in a megaproject in Jerusalem known as Holyland, which became the center of a corruption scandal that led to the resignation of Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. As the project was collapsing, Feldman asked Meir, a native Hebrew speaker, for help.

When Feldman launched HFZ Capital Group, he took Meir with him. Meir had a knack for numbers and an unrivaled ability to woo investors, according to sources.

“We used to joke, a loan is due and Nir would jump on the next plane and come back with a bag full of money,” one former HFZ employee said.

Short, buff and with a defined jawline, Meir was an intimidating presence around HFZ’s Madison Avenue office. Feldman eventually appointed him manager.

“He was always running around on the phone, yelling at people,” Feldman’s assistant said in a deposition.

“I can’t stress enough how powerful he was over me and the rest of the employees in the office,” she added. “It’s hard to explain unless you met him, you spent some time with him.”

At times, Meir was friendly. At others, frantic.

He would send rapid-fire emails and texts.

“Please call me.”

“Really need to talk.”

“Two minutes.”

Meir did not always give the impression of a man in control. Once, an associate from Beny Steinmetz’s companies emailed an attorney involved in the XI that Meir “was worried.”

The attorney responded, “Nir is always worried.”

Meir’s emotions would cycle. When a contractor would call to demand tens of millions of dollars for completed work, Meir would first yell, then beg. By the end of the conversation the two would be friends, laughing about all the money they’d make, a former employee said.

“It was crazy phone call after crazy phone call,” said the former employee.

For a time, HFZ was the “it” company in New York real estate. The Daily News called Feldman a “modern-day John Jacob Astor.” The firm carved out a niche converting and restoring historic landmarks into swanky condos. Its projects — the Belnord, the Astor, the Chatsworth — appealed to blue bloods, a clientele not drawn to the glass and steel towers of Billionaires’ Row.

Meir, from Israel, and Feldman, from Queens, weren’t from that world. They didn’t have generational wealth. Meir idolized Napoleon and the American robber barons: conquerors.

Meir lived to impress others, especially those who already had everything. Israeli auto magnate and HFZ investor Yoav Harlap recalled him showing up at his house in Israel in a fancy suit.

“I remember thinking to myself how crazy it is to come with a three-piece suit in Israel,” Harlap said in a deposition. “It was kind of totally out of place.”

Real estate was the perfect place for Meir. It’s a business of back rooms and see-and-be-seen galas. Condos are purchased through anonymous Delaware shell companies. Income statements can be manipulated to obtain larger loans. Appraisals are a joke. There are no disclosure requirements. As an investor, you have to trust the developer. If they screw you, too bad. Sue, but you’ll likely lose again.

Money moves

In this shadowy world, Meir appeared to be in his element. He could persuade the world’s moneyed and powerful that investing in HFZ was about prestige. But once he had funding, his plans did not hold up. Projects would run short on money, though Meir never seemed to.

He was the point person for Steinmetz, one of Israel’s richest men and among HFZ’s largest backers. (Steinmetz had reaped $500 million from mining rights in the mountains of Guinea. A Swiss court later found he had bribed high-ranking officials there.)

For years, HFZ denied Steinmetz was involved in the company, but in 2021 The Real Deal discovered a chart showing that he was a 60 percent owner of the Belnord.

It’s low to lie to a reporter. But lying to lenders and the government is illegal.

Meir took $65 million from HFZ projects to cover shortfalls on other HFZ buildings and line the pockets of HFZ executives, the Manhattan district attorney alleges in an indictment. He wouldn’t be the first to borrow from Peter to pay Paul in a mad scramble to get projects done.

But Feldman believes Meir was taking a lot for himself: $11 million on a personal American Express card the company paid off, another $30 million from a cash-out refinance in Chicago.

It wasn’t just alleged theft. The projects were undercapitalized. Meir pushed problems down the road, relying on constant activity to keep tranches of funding coming in.

HFZ bought 76 11th Avenue, the site for the XI, for $870 million, the most ever paid for land in New York City. Designed by starchitect Bjarke Ingels, the project was supposed to be HFZ’s magnum opus. Its two towers would twist above the High Line like an optical illusion.

Children’s Investment Fund lent $1.3 billion for the XI in 2017. Meir allegedly diverted about $253 million over the course of four years, instructing accountants to forge financials, and contractors and subcontractors were left with a $37 million shortfall.

In NoMad, Meir allegedly moved $107 million that was supposed to pay for a 34-story office tower to other HFZ projects and the accounts of HFZ executives. When invoices came due, HFZ left a shortfall of $24 million.

Meir also allegedly directed HFZ accountants to not pay $15 million in property taxes.

Outside New York, Meir was even more brazen. In 2017, an investor put $5 million toward a property in San Francisco. Meir sent fake brochures and permits showing progress on the project, according to the D.A. But HFZ never acquired the development rights.

One former employee asked why prosecutors only focused on a few HFZ projects when Meir was moving money from everywhere.

Maybe Meir was bad at business. A Saudi Arabian investor in the Chatsworth raised a red flag after not receiving a distribution despite a refinancing. Meir never finished an Upper East Side assemblage.

Sometimes contractors, including Omnibuild, threatened to walk off sites, but Meir paid them just enough to come back. Lawsuits show that investors were promised condo units at the Astor and other projects that were never delivered.

On top of all this, Meir was constantly taking new loans from friends and portraying himself as HFZ’s savior.

“He was screaming at me that without him the company wouldn’t survive because he was single-handedly making investments on his behalf to keep it afloat,” Feldman said in a deposition.

Freezing the money flow

When the pandemic hit, construction of the XI stopped, exposing Meir’s tangled dealings.

Lenders CIM Group and Starwood threatened to foreclose on other HFZ projects, so Meir sent fake wire transfer confirmation numbers to buy time, according to lawsuits. A $750,000 check to another investor bounced, court filings show.

He grew reckless. In September 2020, Meir took a $30 million loan from Wix co-founder Avi Abrahami, pledging a portfolio of industrial properties as collateral. But Meir failed to tell Abrahami that the same properties backed $43 million in debt from Monroe Capital, which had provided a $113 million corporate loan, according to depositions.

Monroe’s corporate loan was secured by interests in most of HFZ’s properties. It was debt that could end HFZ.

Feldman said he found out about the Abrahami loan in late 2020 and confronted Meir.

“He went berserk,” Feldman said in a deposition. “He said, ‘I’m here to save the company, it was a great loan that I got, and I didn’t need to tell you.’

“We discovered where all the money went. Four million went to him personally. I called him up screaming and crying in front of my son, ‘What the fuck did you do?’ And he then proceeded to tell me, ‘What are you talking about? I borrowed this money from friends of mine to keep the company afloat and now I’m paying them back.’”

To hear Feldman tell it, Meir is not just a bad guy — he’s a sociopath. His act at the office all those years wasn’t just real estate swagger. Meir could read emotions and put people under a spell.

“By the end of the day you will be in charge and dealing with all the craziness and stress I have been dealing with everyday. Good luck.”

He isolated employees, telling one person one thing, others the opposite. He allegedly forged Feldman’s signatures. To make it seem like HFZ was in good health, he created fake financial statements with the help of the CFO.

Not everyone buys Feldman’s story of victimhood. How could Feldman be so ignorant? He must have known, they suggest. But Feldman maintains that they underestimate Meir.

“Four percent of the population are sociopaths,” he said in a deposition. “There was a movie called ‘The Undoing’ with Nicole Kidman and Hugh Grant several years ago. So he threw his son under a bus to prevent himself from going to jail. Nir is at the highest level of that.”

Asked whether Nir had been diagnosed, Feldman said: “That would require going to the doctor to get a diagnosis. Perhaps when he’s in jail, they will diagnose him then.”

Meir could not be reached through his court-appointed lawyer. Feldman declined to comment for this story.

In December 2020, Feldman fired Meir. The XI headed to foreclosure in the summer of 2021.

Miami spiral

Many families moved to Miami in 2021, Meir’s among them.

His wife, Ranee Bartolacci, thought it was a lifestyle choice.

Bartolacci, whose family had owned a beloved supermarket chain in Pennsylvania, got engaged to Meir in 2008, on Christmas Eve in Paris. They married a year later at the Plaza in New York. Kool & the Gang performed.

Meir had other reasons for the move. He had known for at least a year that trouble was ahead, and acted to protect himself.

He lacked equity in HFZ, so for money he transferred the HFZ-owned Southampton home where he was living into his name, allegedly altering documents to do so. Then he sold it for $43 million. When a creditor went after the proceeds to collect on an $18 million judgment, Meir’s lawyers said the home wasn’t his — it was his wife’s. The court allowed a judgment to be entered against Bartolacci.

Meir was elusive outside the courtroom as well. When he spotted a process server, he sped off, making U-turns, zig-zagging through parking lots. Another server alleged that Meir tried to run him over.

“He just cursed and yelled at me,” one said in an affidavit. “The guy is insane.”

Meanwhile, frustrated creditors saw money flowing in and out of various accounts: to a Delaware bank specializing in asset protection, to Qatar, to purchase $1.6 million in gold. Princely sums were frittered away on fine wine, private jets, yachts, hotel stays and Miami strip clubs E11EVEN and Gold Rush Cabaret.

Meir was held in contempt of court for moving money out of restrained accounts. A New York judge called his tactics a “shell game.”

In early 2023, Meir’s spending caught up with him. He and Bartolacci were evicted from their rented Miami mansion.

Bartolacci moved into her parents’ house and, by her account, tried to make sense of what had happened. She plumbed her husband’s legal issues, discovering the judgement against her over the Southampton home.

Eventually, Bartolacci texted Meir about her findings, but he dismissed them.

“The judges didn’t order or sign any order of contempt against anyone because they haven’t submitted the evidence to support such,” he replied.

In text after text, Meir asked Bartolacci to call him or his attorney, Larry Hutcher. When she didn’t respond, Meir grew erratic.

“By the end of day you will be in charge and dealing with all the craziness and stress I have been dealing with everyday. Good luck,” he wrote.

Bartolacci had heard enough. She filed for divorce. Meir started living in fancy hotels.

Day in court

Meir had lied to The Real Deal over the years, about HFZ and his litigation. His requests to delay publication of stories became tedious. Sources warned that he was sketchy, or worse. Feldman concluded that Meir was a sociopath or some sort of Svengali. The D.A. alleged that he was a criminal.

This reporter found him unconvincing and never saw the charm that sucked others in until an episode about a year ago when he called after the Miami Beach eviction. His family hadn’t been evicted, he claimed; rather, the landlord had violated his lease because of a collapsed sea wall. He sent photos of a notice of violations posted at the entrance to his home.

He talked fast but somehow also calmly. He wanted an email sent to his lawyer for more documents; the email went out. Later he said it was the wrong request and should have been about a separate lawsuit. That follow-up went out, too.

Reporters try not to be credulous even about small things, but this was his mystical effect. When you’re with Meir, his reality becomes the truth. His tone of conviction sucks you in.

On Feb. 5, four days after Meir filed for bankruptcy, Miami Beach police officers showed up at the 1 Hotel & Homes with a warrant.

Just before his arrest, Meir was texting real estate people, seeking loans of $15,000 or $25,000. Before the 1 Hotel, he was living at the Four Seasons in Surfside. Meir was dating a woman going through a divorce, rumor had it, and had persuaded her to let him sell her diamond ring.

The D.A. needed a week to get custody of Meir, who had failed to turn himself in after his charges were announced. Meir pleaded ignorance about his pending arrest, and at his bail hearing in New York, he pleaded not guilty.

At the hearing, he looked frail, as if he had aged 15 years, but with the same dead-set dark eyes. His clothes were too big for him. In a soft voice, he asked the judge if guards could remove his handcuffs so he could speak.

He’d only run into financial problems during Covid, Meir said. He asked if he could schedule court check-ins instead of having to post bail.

The judge denied his request. Rasputin’s mist evaporated. The power was gone, for now. The judge set bail at $5 million cash, which Meir has yet to post.

Meir stuck to his lies — though they now sounded more pedestrian, like anyone having his day in court.

“I’m a 49-year-old guy, never had any priors, never been arrested,” he said, “I have been an upstanding citizen all my life.”