When Leonard Rabinowitz and Jack Friedkin left the Agency in September to join Hilton & Hyland, and Jay Harris took the same route two months later, the moves didn’t raise many eyebrows. Rabinowitz and Friedkin had been at the Agency four years, and Harris seven, but jumping ship has become more common in an era of brokerage consolidation.

But then Danny Brown, a partner at the time, left in December, setting off a chain of events more akin to an exodus.

In March, the Agency lost Cindy Ambuehl, a longtime partner, as well as David Kelmenson, a former partner at Partners Trust. The following month, managing director Don Heller left, followed by Stephen Sigoloff, director of residential estates, and most recently, top producer Dan Urbach.

Mauricio Umansky, Billy Rose and Blair Chang launched the Agency in 2011 to much fanfare. Its charismatic leaders sought to shake up the brokerage landscape with sleek branding and a star-studded approach to marketing — it was real estate, Hollywood style. “Nobody had come in to disrupt it [the business], to revolutionize it, to innovate it,” Umansky had said of the decision. The firm became emblematic of boomtown L.A. and was involved in some of the city’s priciest deals. Yet nowadays, even as the Agency celebrates new offices and throws $100,000 open-house events, a grim scene is playing out behind closed doors.

Between January 2018 and June of this year, the firm lost 45 agents in L.A. County, many of them big producers. That’s about 15 percent of the 303 agents it had in June, according to data on licensed employees from the California Department of Real Estate.

The company has been quick to fill the vacancies, adding 140 new agents in the same period. Still, that turnover is about double the number seen at Hilton & Hyland. Compass, which is around five times bigger in L.A., saw 55 agents leave during the same time.

The departures come as the Agency and Umansky fight a legal battle with the vice president of an authoritarian Central African nation over Umansky’s sale of his Malibu estate. Meanwhile, co-founder Rose stepped down as the firm’s broker of record weeks before the litigation was filed.

But brokers say it’s not just the legal drama that pushed them out. They criticize the firm’s emphasis on “sharing,” which some see as a euphemism for management piggybacking on agents’ hard-won listings.

For this story, The Real Deal interviewed many former and current Agency agents, as well as several outside industry leaders. Some think the Agency has lost its edge amidst its rapid expansion, which has seen its office count nearly triple over the past two years to 33 and its total agent roster balloon to 585. And while its founders still refer to the company as a “boutique,” it’s no longer got the small-shop feel that set it apart.

“When they had one office, that was when they really blossomed,” said Aaron Kirman, a top luxury broker at Pacific Union International, now part of Compass. “I think where they started the decline is when they started getting multiple offices. Now they have offices all over the place. At that point, it’s hard to protect the brand.”

Coming in hot

The Agency burst onto the scene as the market was bouncing back from a recession. Developers were starting to put multimillion-dollar bets on spec homes, a practice that would transform the Southern California landscape and create scores of high-priced new listings. New agents, hungry for their first million, were flocking to the action.

Umansky had established a stellar track record at Hilton & Hyland, emerging as the firm’s top producer for seven years running, while Rose and Chang were running their own top-ranked team at Prudential. In 2011, the trio created the Agency, setting up shop in a 1,800-square-foot office on Beverly Drive. The space was modest, the ambition anything but.

Umansky had established a stellar track record at Hilton & Hyland, emerging as the firm’s top producer for seven years running, while Rose and Chang were running their own top-ranked team at Prudential. In 2011, the trio created the Agency, setting up shop in a 1,800-square-foot office on Beverly Drive. The space was modest, the ambition anything but.

“I believed that the brokerage model was sort of broken, and I thought there was an opportunity to start a company that sold real estate differently,” Umansky said. “The mission was to create a boutique firm with global reach.”

Jason Oppenheim, founder of Oppenheim Group, said the Agency was a pioneer in breaking from the “brokerage-centric model,” where the name of the brokerage mattered more than the individual agent. Calling it both “inspirational and risky,” Oppenheim said Umansky was asking people to join an Agency that “didn’t have its bearings under it.”

The gambit worked. Agents and clients were attracted to the firm’s approach, which included the market’s first luxury lifestyle newsletter.

“I remember being really impressed at the time,” said Spencer Krull, general manager at Westside Estate Agency in Beverly Hills. “Their marketing at the time was really different than what anyone else was doing. They came on the stage very strong.”

Not only did the Agency offer full marketing support to its brokers, it would promote those capabilities to potential clients to win business. It also went full-tilt on open houses, which before the firm came along were largely sedate affairs. A 2013 open house for a $29 million listing on Sunset Plaza featured celebrity chef Michael Voltaggio, $3 million worth of Lamborghinis in the driveway, a DJ and an open bar. The parties have since escalated to include champagne-pouring aerialists and pop-up breweries.

Fueled by a strong market, Umansky and other Agency brokers would also often price homes at numbers that appealed to sellers, sources said. Umansky denies such claims.

“When they got in the business, we were on an uptick,” said one broker. “You could get away with a lot of things. And they had that swagger and that hip vibe, so the timing was great.”

Umansky also wielded a trump card few other agents could hope to: exposure on national television. His wife, Kyle Richards, had been the star of Bravo’s “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” for a year at the time, giving Umansky and his fledgling company a free platform from which to promote their business. Former agents recall instances where Umansky and now-“Million Dollar Listing Los Angeles” stars David Parnes and James Harris would persuade clients to list with them by luring them with the prospects of being filmed for television.

“We do use television to our advantage, like all the casts of these shows,” Umansky said. “We are lucky enough that people want to pay us to be on TV, not the other way around.”

As for agents, Umansky said he “did zero recruiting.” “We wanted to be a boutique, a high-service firm, and it was more like a club that people wanted to be a part of,” he added.

Sources agree that the Agency did not “recruit aggressively” like companies do today, but said it was common for early agents to attract their friends and other high performers. Heavy hitters like Jeeb O’Reilly, Kofi Nartey, Heller, Sigoloff and Ambuehl were among the first to join.

“The thought of starting a new agency from ground zero was so exciting,” said O’Reilly, who had joined from Hilton & Hyland. “I felt we had the greatest formula. We had fabulous public relations, fabulous marketing and a great vision.”

The Agency started winning — and selling — big listings. In 2014, Umansky sold the palatial Carolwood Estate, once owned by Walt Disney, for $74 million. He was then involved in the record-breaking $100 million sale of the Playboy Mansion two years later. While Umansky was by far the biggest rainmaker at the firm, other agents made bank, too: Santiago Arana, now a partner, sold the home used in “Beverly Hills Cop” for $23 million in July 2015, two years after selling Larry David’s home in Pacific Palisades. Ambuehl landed $20 million for the home of “Full House” creator Jeff Franklin that same year. Rose broke a record in Santa Monica’s Sunset Park when he sold Ryan Phillippe’s home for $15 million.

Sharing is caring

By many accounts, the Agency’s honeymoon period lasted for just under five years. Serious issues then began cropping up.

“I couldn’t stay because they had stolen a big client from me and lied about it to my face,” O’Reilly, who left the firm in 2015 and is now at Compass, said. “When I brought it up, they just looked at me and said, ‘We didn’t know you were working with her.’’’

Other agents told a similar tale.

“Any time we would try to bring a listing, they would say, ‘You don’t need to work on this listing’ and just take every single deal out of our hands,” recalled one. Another remembers an instance when an agent mentioned an A-list celebrity client at an all-hands meeting, and the owners then went after that client. When the agent complained, they were told it would be made up to them at a later time. It wasn’t, they said.

Agents who joined the company were sold on a notion of “sharing” and “collaboration,” they said. The idea was that founders would pass on listings to rising agents for a small referral fee. For a 50-50 split, agents could also tap into a principal’s expertise to sell a listing.

But those splits didn’t always come to pass, sources said. In one instance, an agent’s commission ended up being much lower because marketing and other expenditures were taken out of the agent’s share.

“My check should have been for $100,000, but I got $5,000,” the agent said. “They were robbing us blind.”

While Umansky said it’s “sad” people feel that way, he contends that sharing is central to the business model.

“If we were stealing clients, we would not be able to expand our business,” he said.

While the model worked for some younger agents who may not have secured a $20 million listing without Umansky’s clout and public profile, it didn’t sit well with others who now say it was a bait-and-switch structure that mostly benefited the owners.

“Between the [owners], they had tons of business,” said one former agent. “They were saying that everything was going to be a team effort, and that they were not interested in being salespeople. It ended up being complete lies.”

Umansky denied that this is an issue at the company. While he said he has heard “rumblings,” he maintained that the Agency “shares more, gives more than anybody else.” Umansky currently has 43 active listings, valued at more than $1 billion, an Agency spokesperson said.

“When you are doing incredible stuff,” he said, “you have a target on your back.”

Supporters argue that other firms in L.A. utilize the same tactics. The broker-owner model, Oppenheim said, works because the brokerage has two sources of income: the broker’s listings and its agents’ listings.

“They’re able to leverage the ownership to bolster their own real estate business as agents,” Oppenheim said. His firm and Hilton & Hyland work in a similar way, he added.

“I think that his [Umansky’s] name on listings has actually really helped smaller agents who are looking to catapult to the next level,” said Ambuehl, who left the Agency in March. “Mauricio is not putting himself on everyone’s listings so he could be the big dog.”

Westside woes

The situation appears to be especially fraught in the firm’s Brentwood office.

Several of the firm’s former top producers who were based in that office are out. One broker described it as “an absolute mess.”

Sources cited issues with Arana, who is the managing partner at the office. They said he prioritizes selling over managing, often putting himself on listings or going after major clients.

“A lot of agents felt like the person running it was having practices that were not aligned with their interests,” said a former agent. “It’s become problematic.”

Arana rejects the idea that he is running the show — that job, he said, belongs to Doug Sandler.

“I have a managing partner title, but I wouldn’t call myself a manager because if I was then I wouldn’t be selling,” he said. Arana also develops: Two houses he built in Brentwood have sold to LeBron James and Formula One heiress Petra Ecclestone.

“The only listings that I have my name on with other agents is because they needed me to help get the deal done, or because I brought them in,” he contended.

Arana is the only Agency broker to crack the top 10 in TRD’s ranking of top brokers this year, coming in seventh with nearly $247 million in sales volume between March 2018 and February 2019. Harris and Parnes, also at the Agency, ranked No. 11 with $162 million in sales. Umansky declined to participate in the ranking.

At the Brentwood office, the Agency lost Ambuehl, Kelmenson, Heller, Sigoloff and Brown to Compass.

“I think quite honestly what’s happened to us at the Brentwood office is that Compass has a great recruiter, and they found a hole,” Umansky said. Arana is “an extraordinary leader” who “is doing none of that,” he added.

Ambuehl, who declined to comment on the Brentwood office, said that Compass, backed by SoftBank and valued last year at $4.4 billion, is “changing the rules of the industry.”

Ambuehl, who declined to comment on the Brentwood office, said that Compass, backed by SoftBank and valued last year at $4.4 billion, is “changing the rules of the industry.”

“That’s one of the big things the Agency and other agencies are going to be faced with,” she added.

A spokesperson for Compass said the firm is “humbled” anytime an agent from the Agency chooses to join Compass but declined to comment specifically on the Brentwood hires.

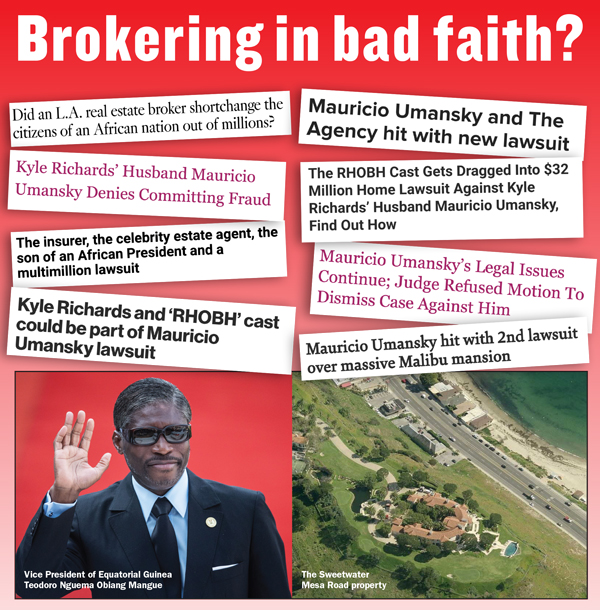

The curious case of Teodoro Obiang

“Did an L.A. real estate broker shortchange the citizens of an African nation out of millions?”

On the morning of Sept. 30, 2018, peering out from the Los Angeles Times’ business section, was the above headline. In a bombshell lawsuit, Umansky was accused of intentionally selling a 15,000-square-foot mansion on Malibu’s Sweetwater Mesa Road for millions less than it was worth, in order to later personally profit from the resale. The suit claimed Umansky had partnered with the buyer in a plot to resell the home for a far greater sum.

Umansky had been tapped to sell the home after the U.S. government accused owner Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the vice president of Equatorial Guinea, of using stolen funds to purchase the property.

Within seven months of listing, Umansky found a buyer. L.A. real estate investor Mauricio Oberfeld paid $33.5 million for the home in December 2015, and Umansky partnered with him on the purchase. However, the two resold it a year later for $70 million, more than twice what they paid, leading Obiang to sue Umansky and the Agency for damages and any profits made from the sale. Umansky maintains that he acted in good faith in the sale, which was supervised by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Western World Insurance filed a lawsuit against the Agency last August to protect itself from having to pay any damages to the seller, who was demanding that the Agency cough up $8 million for misrepresenting the value of the home. The Agency countersued, and the suit was dropped in October.

The seller has since taken matters into his own hands. Obiang filed his lawsuit in federal court in March and is suing Umansky and the Agency for damages and any profits made from the sale. Umansky and the firm maintains that the broker acted in good faith in the sale, which was supervised by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Umansky declined to comment on how the litigation has impacted the business. It’s clear that it was a public relations hit for the firm, but brokers said that such lawsuits are part of the cost of doing business at the top of L.A.’s real estate market.

“You can’t be a successful agent and not be drawn into some type of litigation,” Oppenheim said. “It’s almost a sign of being successful.”

Rather, it’s the actions taken by co-founder Rose around the time of the lawsuit that are more alarming, industry players said.

In the weeks leading up the first lawsuit, Rose stepped down from his role as the firm’s broker of record. He tapped Michael Caruso, who had been at the Agency less than a year at the time, to replace him.

Chang, the third co-founder, has kept a lower profile than his counterparts. He has about 15 active listings ranging from $2 million to $16 million, according to the firm’s website.

While the firm maintains that Rose stepped down in order to focus on “serving his clients,” others claim it was because of the lawsuit. Or worse, they say, the firm’s lack of funds pushed him to spend more time winning business.

“Don’t you think its weird when your managing partner resigns?” said one broker. “All of a sudden he’s back selling real estate, focusing on building the brand. That’s a sign.”

“What is he so afraid is going to happen that he’s removing himself from it?” another broker said. “It raised a lot of red flags.”

Built to sell

The Agency closed $4 billion in sales volume in L.A. County in 2018, ranking fifth on Los Angeles Business Journal’s list of top residential brokerage firms. That’s about 14.2 percent higher than its volume in 2017, when it closed $3.5 billion.The firm ranked behind Compass and Rodeo Realty, but beat Hilton & Hyland and Westside Estate Agency in the ranking. A spokesperson for the Agency added that the firm closed more than 2,000 transactions last year.

As of July 8, the Agency had 237 listings in L.A. County, according to an analysis of single-family and townhouse listings on the Multiple Listing Service. That’s nearly $1.6 billion in sales volume, which is roughly 40 percent less than Hilton & Hyland and Compass. The figure does not include off-market listings.

The Agency is actively expanding, pushing for more offices in Northern California as well as several others on the West Coast. This is at a time when luxury real estate markets are softening: In March, home prices in Southern California fell year over year for the first time in seven years, and a Douglas Elliman first-quarter report revealed that the number of luxury home sales in L.A. County dropped 31 percent year over year. Discounts on top-end estates have become standard.

Those in the business wonder whether the Agency’s flashy approach will serve it well during a slowdown.

“It’s going to be rough for them,” said one brokerage executive. “This is the first time they see a down market. I wouldn’t be surprised if they start to scale back a bit, or consolidate.”

Yet Umansky welcomes the challenge. He stressed that losing many talented agents hasn’t hurt the business, with offices running at capacity and new recruits replacing those who’ve moved on. For example, Sandro Dazzan, a former top producer at Coldwell Banker, joined to lead the firm’s Malibu office in February 2018.

“In my eyes, we haven’t lost anybody, because we have maintained the number of agents per office,” Umansky said. “Having said that, you usually see a lot of change in life during the time when markets are down.”

The firm began a franchising push a few years ago, expanding into international markets like Mexico and the Caribbean. It also has franchises in Turks and Caicos; Punta de Mita, Mexico; Victoria and Nanaimo, British Columbia; Park City, Utah; and Boca Raton and Jupiter, Florida. And it’s looking to enter markets in Tennessee and Texas, with an eye, when the “timing is right,” on the richest market of them all, New York City.

Industry veterans have questions about the firm’s endgame. Aggressive expansion like this is often a sign that the firm is prepping for a sale, they said.

“It appears as though, with all they are doing, they are setting up to sell it,” said Stephen Shapiro, co-founder of Westside Estate Agency. “I think their goal is probably to get as many satellites as they can and maybe they take whoever is ready to jump in instead of taking their time and doing it more slowly.”

Though the founders have long denied such claims, Umansky said he will consider “mergers and acquisitions.” Others point to failed 2016 discussions with New York-based brokerage Town Residential as support for the claim that the founders are looking to cash out.

Town had been in talks to potentially buy or merge the two firms. A source familiar with the deal said Town eventually pulled out after analyzing the Agency’s financials, which showed that the bulk of the business was in the hands of just a few power players. (Town ultimately closed in April 2018.)

Umansky claims it was the other way around.

“We were in talks to acquire them, not them to acquire us,” he said.

The Agency had made less than $1 million in net income in the 36 months ending December 2014, TRD reported at the time, citing financial statements Rose filed as part of his divorce proceedings. The filings showed that during that period, Rose took home $3.63 million in personal commissions plus nearly $360,000 in net income from his ownership stake in the firm.

“If they left, the company would make no money because none of these brokers would be able to land the business they land,” a source said in reference to Umansky and Rose. “They use their star power and their stature to make them bigger, and in turn sell that back to brokers who lack confidence or a brand name.”

The Agency has also been digging its teeth into new development. In 2017, the firm took over selling condos at Greenland Group’s Metropolis development in Downtown L.A. from Elliman. It then lost that listing to Polaris Pacific this past February, though Umansky hinted there have been “discussions” to potentially revisit selling the luxury units.

Sources questioned the legitimacy of their offices outside the Golden State.

In South Florida, one broker who was involved with the company there said the founders “didn’t do their due diligence” and ended up hiring “nobodies” to run the office.

“Franchises can be difficult because it’s all based on the culture you build, and every culture is different,” said Pacific Union’s Kirman. “I think it just led to a loss of the Agency having their identity.”

But to the face of the Agency, their growth has been “incredibly slow.”

“We’re a boutique,” Umansky said. “I’ve never bought a company. I don’t have $400 million. This is real growth.”