The City of L.A. enters the runoff campaign for an increasingly heated mayoral race as a new anti-corruption law takes effect to prohibit developers who are pursuing entitlements for certain projects from donating to any political candidates.

The city passed the law in late 2019 — while revelations were unfolding in an ongoing political corruption scandal that has highlighted illicit ties between City Hall and real estate interests — but scheduled it to take effect in conjunction with this year’s general election. The time gap was also needed to allow the city to better figure out who the law would apply to, officials said at the time.

The law applies to developers — a group that includes property owners, project applicants, and company principals — who have major projects pending before the city. The prohibition applies to the mayoral race as well as other citywide offices and contests for the City Council. The law also requires developers pursuing the designated projects, which includes all Transit Oriented Communities projects, for example, to register with the city’s ethics commission.

The ban does not apply to developer Rick Caruso’s practice of largely self-funding his campaign. The developer of The Grove and other retail centers around Southern California put an estimated $37 million behind an advertising blitz that helped him secure a spot in the runoff, where he’s squaring off with U.S. Representative Karen Bass after the two polled nearly evenly in the first found voting on June 7,

An analysis by TRD published last month found that the real estate industry, including developers, had contributed significantly to what was then the mayoral primary: By late April, with weeks to go before the primary, Bass had taken in over $100,000 from the industry, and at least $23,000 from developers, TRD found, and councilmember Kevin De León, a veteran politician who counts development-heavy Downtown Los Angeles as part of his district, had taken in over $170,000 from real estate players and $52,000 from developers.

TRD did not analyze how many, if any, of those developers currently had projects before the city. All of those political donations also paled in comparison, in any case, to Caruso’s largesse on his own behalf.

Caruso, meanwhile, has also made a point to emphasize his own ethics considerations: He has previously promised that if he’s elected he will place his company in the hands of a blind trust, and that it would not pursue any City of L.A. projects during the duration of his tenure.

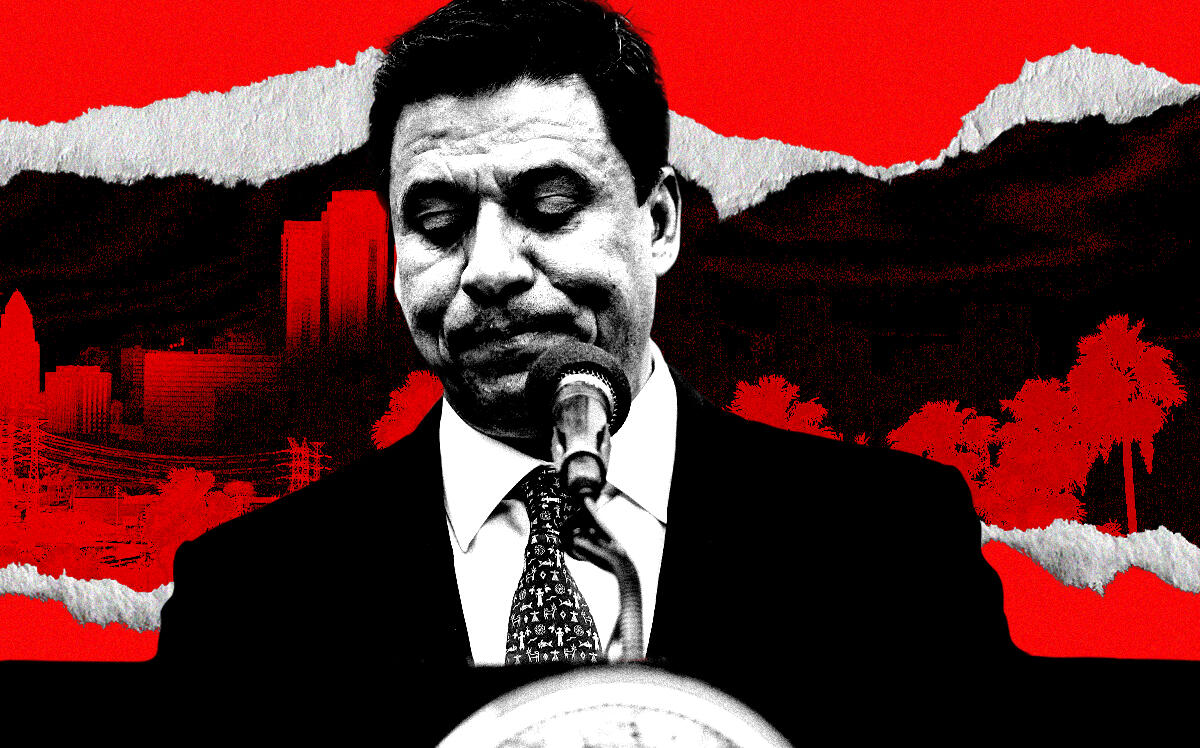

In July of 2020, after a six-year FBI probe, a federal grand jury indicted Jose Huizar, a powerful L.A. councilmember, for accepting over $1.5 million in bribes from developers in an alleged pay-to-play scheme. Since then a number of others involved in the scandal, including former councilmember Mitch Englander, have pleaded guilty; earlier this spring the upcoming trial for Huizar, who has denied the allegations, was delayed until early 2023.

L.A. ‘s just-enacted anti-corruption ordinance was first proposed around late 2016, the L.A. Times previously reported, but finally passed in late 2019 amid the burgeoning Huizar scandal.

Yet at the time a host of critics, from both inside and outside government, also blasted the law for not going far enough: While it bans developers from donating directly to candidates, it does not ban them from hosting fundraisers or otherwise raising money for them. And the law does not apply to project subcontractors.

At the time one of those critics, the developer Tom Gilmore, told the paper the law amounted to “a nice PR stunt at best.”

“I don’t think it’s meaningful to block developers from giving $800 checks while still allowing them to raise $20,000,” he added.

Some elected officials also expressed skepticism at the time.

“Do I think this is going to solve all corruption? Of course not,” then-councilmember David Ryu, who lost a reelection bid in 2020, said at the time. “But this is something that has been needed in the city of Los Angeles for decades.”

Erik Eusebio, the manager of the city’s ethics committees’ developer program, did not immediately respond to an interview request on the implementation of the ban.

Read more