The government of Kuwait is suing the country’s former defense minister over more than $100 million in funds that were allegedly embezzled from the oil-rich state and pumped into luxury properties in Los Angeles.

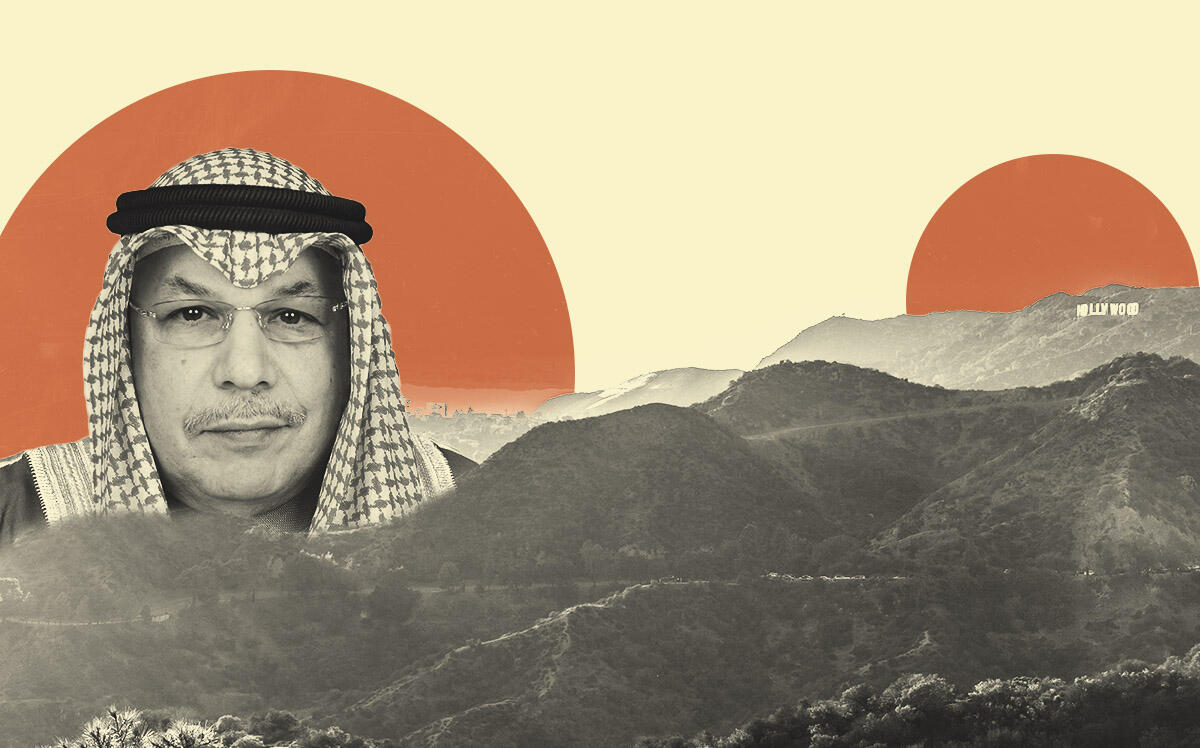

The suit, filed on May 20 in L.A. County Superior Court, focuses mainly on Khaled J. Al-Sabah, a decorated Kuwaiti military figure who served as defense minister from 2013 to 2017 and is also a member of the country’s ruling family.

“The funds that Al-Sabah misappropriated and embezzled from Kuwait are public funds of Kuwait and rightfully belong to Kuwait,” the suit claims. “As such, Kuwait has a right to payment from Al-Sabah in the amount to be proved at trial, but not less than $104 million.”

An L.A.-based lawyer who is representing Al-Sabah on a separate case did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Al-Sabah himself could not be reached, and it remains unclear if he has retained another lawyer for the case brought by Kuwait. A lawyer representing the government of Kuwait also did not respond to a request for comment.

The new civil suit, which was filed by the “government of the state of Kuwait,” comes several weeks after a Kuwaiti court acquitted Al-Sabah and another high-profile ex-minister on criminal charges related to the same allegations. For years, a story of nearly $800 million in missing military funds has riveted the Middle Eastern nation, which counts some 4.3 million residents and has been ruled by the Al-Sabah family for decades.

The recent criminal case was widely seen as a test of government accountability, and to many the court’s criminal acquittals proved the government’s push to root out corruption was a failure, the Associated Press reported.

“We don’t know where the money that was stolen in the army fund went, and many other billions missing with it,” one Kuwaiti opposition figure tweeted. “But I am certain that the corrupt and their supporters will be punished in this world and the hereafter.”

The new lawsuit in Los Angeles County court appears to be an attempt by certain members of the Kuwaiti government to seek redress in the American court system in the wake of the loss in criminal court in their country. It also amounts to the latest twist in the long, complex saga of one of Southern California’s most notable properties, and highlights the prominent place L.A. luxe real estate commands among the machinations of the global elite.

It’s a saga that can be traced back, in part, to what was arguably the splashiest listing in real estate history. In July of 2018, the celebrity broker Aaron Kirman put a new property on the market with a price tag of $1 billion — a price purported at the time to be the higher ask ever in U.S. history.

The property was the so-called Mountain of Beverly Hills, a never-developed, 157-acre piece of land located at 1652 Tower Grove Drive, the highest point in the 90210 zip code. Along with stunning views, the property represented a kind of holy grail of L.A. spec development: It was once owned by an Iranian princess, who had plans to build a palace at the site, and was later acquired by entertainment industry legend Merv Griffin, who had his own plans to build a mansion with the famed designer Waldo Fernandez. In 1997, Griffin ended up selling to Mark Hughes, the founder of Herbalife, for $8 million.

Hughes died in 2000, and his estate later sold the property to an Atlanta investor, Chip Dickens, who borrowed $45 million from the Hughes estate to buy it. Dickens later partnered with Victorino Noval, formerly known as Victor Jesus Noval, a wealthy film financier. Noval was convicted in 2003 on charges of mail fraud and tax evasion and sentenced to 57 months in federal prison.

It was an entity tied to the new owners, called Secured Capital Partners, that eventually contracted Kirman, who traveled around the world in an effort to entice billionaires as he promoted the eye-popping listing.

“If it’s a marketing stunt, it worked,” Mark McLaughlin, at the time an executive with Pacific Union and Kirman’s boss, told TRD in 2018. “It’s gotten an incredible amount of attention.

But attention never translated into a sale: Some eight months after the $1 billion listing, in February 2019, the owners lowered the ask to $650 million, and a few months later the property — which by then was the focus of its own legal battles and heavily indebted — went up for foreclosure auction.

It sold for just $100,000, at a strangely low-key sale held behind the fountain at an outdoor plaza in Pomona. The buyer was the lender — an entity linked to the Hughes estate — whose claims on the property they once owned had ballooned to some $200 million, the L.A. Times reported.

Al-Sabah burst into the saga the next month, after noticing the foreclosure sale. In a lawsuit, he claimed he had been an investor in The Mountain for years, pouring in over $160 million, but was duped by Nova and his son, Victor Franco, who took the money intended for developing the choice land and instead used it to finance “a lavish and extravagant lifestyle” complete with private aircraft, exotic dancers and limousine chauffeurs.

Noval had also allegedly used Al-Sabah’s money to buy more properties; Al-Sabah was seeking nearly $500 million in compensatory damages.

“Based on conservative estimates,” the lawsuit went on, if the Mountain had actually been developed Al-Sabah “would have doubled the initial investment, resulting in a $320 million gross profit.”

So far the courts have not agreed to Al-Sabah’s claims: About a year later, in November of 2020, a judge denied his request to send the properties into court receivership, ruling that he “submits little evidence to corroborate [his] narrative.” (Another status conference on the case is scheduled for October.)

By the time of that ruling, however, the U.S. federal government had also gotten involved. A few months earlier, in July of 2020, the Justice Department — following IRS and FBI criminal investigations — filed seven lawsuits alleging that “former high-level officials in Kuwait’s Ministry of Defense” had embezzled more than $100 million from Kuwaiti public funds. The embezzled Kuwaiti money, the department alleged, had been poured into London bank accounts and then laundered into assets including a private jet, yacht, Lamborghini, even Manny Pacquiao memorabilia — and, mostably, luxe L.A. real estate, including three homes in Beverly Hills, an apartment in Westwood and the so-called Mountain of Beverly Hills.

The Justice Department, which sought to seize the assets, did not name Al-Sabah explicitly, but did name Noval — a convicted criminal, one press release emphasized — who they claimed was tied to the California entities that received the illicit Kuwaiti funds.

At the time a lawyer for Al-Sabah told the press that “any suggestion that my client was involved in any illegal activity is incorrect.” The high-powered Beverly Hills attorney Ronald Richards, who was representing Noval, also told TRD that his client had vetted the source of the funds as a member of the Kuwaiti royal family, and that he had no way of knowing about impromprities or any interest “in retaining any improperly distributed funds.”

Within weeks, the Justice Department settled its suit over The Mountain. (A department representative contacted recently by TRD said he could not disclose any details of the settlement.) The criminal embezzlement case was still unfolding in Kuwait, however, leading the department to stay the other six cases. But the recent Kuwaiti acquittals paved the way for a new American effort, and earlier this month the Justice Department filed another, consolidated asset forfeiture case, seeking the court’s approval to seize various assets from Al-Sabah and others.

That suit names multiple parties, including three Kuwaiti officials (one of whom is clearly Al-Sabah), Noval, Noval’s son Victor Franco Noval, Secured Capital Partners and other entities connected to the luxe Westside properties. It also lays out, in painstaking detail, how the Kuwaitis went about liquidating millions from Kuwaiti government accounts into London and then Los Angeles accounts, providing the money to fund new entities that were used to buy property.

At one point, Victor Franco Noval even attempted to use the laundered money to buy the Playboy Mansion for $100 million, the suit says. An associate used the funds to pay $325,000 for a Lamborghini.

The Kuwaiti government’s civil case names Al-Sabah and 18 more defendants by name, including Al-Sabah’s son Jarrah Khaled Al-Sabah; Noval and Victor Franco Noval; and numerous real estate and financial entities, including Secured Capital Partners — the former owner of The Mountain — and a jewelry and diamonds company. It also names 260 DOE defendants.

It mostly focuses on Al-Sabah, however, whom Kuwait accuses of orchestrating the massive scheme. Kuwait is demanding a jury trial, and a case management conference is scheduled for November.

Read more