In 1626, Dutch merchant Peter Minuit bought the island of Manhattan for the equivalent of $24. Today, an investor would have to fork over roughly $1.25 trillion to buy all of Manhattan including its buildings, according to a recent estimate by The Real Deal — and that’s not counting roads and public parks.

The calculation, based on the city’s assessed land values and recent land sales, is, of course, hypothetical.

But it shows how the value of Manhattan land has ballooned — not just over the last decade, but over the last four centuries.

That rise in value has created vast fortunes for the families and institutions that own even a sliver of prime Manhattan property. But it has also financially squeezed millions of New Yorkers.

This may seem like an unstoppable trend. After all, the supply of land is fixed, while economic and demographic growth have long been in acceleration mode. “Buy land, they’re not making it anymore,” Mark Twain famously said.

But Twain left out an important detail. There is nothing inevitable about the rise in land values. History has shown that they can stagnate, fall and even collapse under the right conditions. While it may seem far-fetched and even unfathomable, those conditions could materialize in New York City in the coming decades.

Stick with me here. Think about what Manhattan might be like 100 years from now. It’s feasible that the island’s land, now incredibly coveted, could be worth a fraction of its current value if transportation technology advances to the point where living close to work and entertainment no longer matters. Super-high-speed trains and flying cars are not out of the question.

The NYC real estate moguls worth millions (or in many cases billions) today could be worth no more than a farmer in, say, Iowa with some good land.

But it’s crucial to understand how land prices have seesawed in the past to comprehend how this could all conceivably play out — or if it will at all.

The 150-year overview

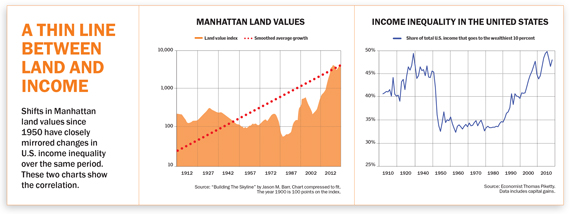

Jason Barr, an urban economist at Rutgers University, created an index measuring the price of Manhattan land from 1866 to 2013, based on data on sales of vacant land.

In the four decades following the Civil War, the United States emerged as one of the world’s leading industrial powers, with NYC as its economic capital. Rapid business and population growth boosted the price of land and led to the city’s first skyscrapers, as Barr’s index shows.

From there, values fluctuated. Between 1900 and 1930, Manhattan land prices rose to a new high, interrupted by a significant dip during and immediately after World War I. For the nearly two subsequent decades — during the Great Depression and World War II — they continued dropping. Prices finally ticked up again during the 1950s postwar boom, but then sank again during the 1970s as white flight and economic decline took hold.

By 1977, land prices in Manhattan had sunk to 1880 levels, according to Barr. Depression, war and urban decline wiped out a century of gains.

Then something changed. Since 1977, Manhattan has seen the fastest and most prolonged period of land-price growth ever (a few cyclical dips aside). Between 1977 and 1988, and again between 1993 and 2007, annual growth averaged a staggering 24 percent.

One possible reason for that growth is government regulations, as Barr explains in his 2016 book “Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers.”

One possible reason for that growth is government regulations, as Barr explains in his 2016 book “Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers.”

During the growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, developers accommodated the strong demand for housing and office space by building taller. That kept a lid on land prices. The logic is simple: As demand for real estate grows, land prices rise — at least at first. But in a competitive market, the rising demand also incentivizes developers to build taller, adding more supply, which in turn depresses prices.

So why did land prices grow so fast after 1977? Cushman & Wakefield’s Bob Knakal chalked it up to one key thing: zoning.

“When zoning came in, all of a sudden you had restrictions on use and restrictions on bulk. What that led to was scarcity,” he said. “The combination of scarcity and location drove land values up.”

Restrictive zoning rules and landmarked districts increased in the 1960s around the same time that rent controls took effect. Those new realities made it harder for property owners to tear down multifamily buildings and replace them with taller ones.

Barr told TRD that until the 1990s there “wasn’t ever this idea that the city needed to expand” to accommodate population growth.

The urban land premium

While zoning laws and rent control are New York-specific, prices in most developed countries followed a similar up-and-down trajectory.

A 2014 study by German economists Katharina Knoll, Moritz Schularick and Thomas Steger found that average home prices across 14 developed countries grew far more rapidly over the past three decades than at any other time since the 1870s. (Home prices are not the same as land prices, but they tend to correlate strongly.) This suggests that New York’s zoning and rent laws are only part of the story.

In addition to zoning, there are two global explanations for why Manhattan land prices have been rising so quickly since the 1970s: fewer advances in transportation and construction technology and increasing wealth concentration. (More on this in a moment.)

Indeed, as cities expanded in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the mass use of cars and railways meant people could suddenly move farther from city centers. But over the past few decades, New York hasn’t seen transportation advances on a similar scale. Sure, cars are a little faster, and you can get an Uber at a moment’s notice. But commuting patterns haven’t changed dramatically since the 1950s.

While construction technology has undoubtedly improved in the last three decades, the way skyscrapers are built has fundamentally remained the same.

That’s a stark contrast from the turn of the 20th century, when innovations such as elevators, ultraconcentrated steel and cheap materials revolutionized building and made it easier and more efficient to build tall.

Robert Von Ancken, an appraiser at Newmark Grubb Knight Frank, said land prices have largely been rising because of growing demand for condos among the wealthiest 5 percent. Demand for condos is up because the rich are richer than ever before and because the wealthy tend to disproportionately concentrate in major cities.

More wealth at the top translates into more demand for luxury Manhattan condos — and the more developers willing to pay for the land to build those pricey condos.

Recent programs by Mayors Michael Bloomberg and Bill de Blasio have attempted to address NYC’s affordable-housing crisis partly through rezoning swaths of the city to allow for more residential development.

But subpar transportation in the Greater New York area, high construction costs and a growing wealth gap are still big problems. So it’s hardly surprising that these programs haven’t actually made NYC affordable.

It’s important to note that none of these factors are set in stone. Although it seems unlikely today, conditions could reverse.

Ricardo 2.0

Before industrialization took off, some of Britain’s wealthiest residents were farmland owners.

Britain’s population was growing, it needed to be fed, and the supply of farmland to meet that growing demand was fixed (Britain being surrounded by water). As a result, rural landowners saw their profits rise.

Economists at the time considered this a real problem.

To the famed 19th-century British political economist David Ricardo, the interests of rural landowners were at odds with society. As the demand for food grew, the owners of existing farmland enjoyed what Ricardo called “rents” — or fortunes that were made simply by owning and renting out land, not by actually producing anything.

As these rents grew, they sapped wealth from more productive parts of the economy, stunting growth, Ricardo argued.

The debate in the U.K. over farm rents at the time wasn’t all that different from the one about NYC apartment rents today. Back then, economists and political activists complained that these owners were exploiting population growth to fatten their wallets. Today, affordable-housing activists make a similar argument about Manhattan’s landlords.

What Ricardo didn’t foresee was that rural land prices would fall in the century following his death in 1823 even as the rest of the economy ballooned, and the landowners would lose much of their relative wealth. When you think of Britain’s wealthiest residents, do you picture farmland owners? Probably not.

That’s largely because starting in the 19th century, technology advances increased agricultural productivity. Suddenly less land was needed to produce the same amount of food, pushing down land values. At the same time, the spread of steamships, railways and refrigerated railcars meant food could now be transported from all corners of the world. Initially, import tariffs kept foreign competition at bay, but the landmark repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 changed that, sending British land prices into a long tailspin.

The question is whether something similar could happen to Manhattan land prices.

Some observers have predicted that the rise of telecommunications technology will diminish the importance of cities.

In his 2000 book “The New Geography,” Joel Kotkin, an urban studies fellow at Chapman University in Orange, California, wrote that the rise of the internet would “redraw the map of wealth and power” away from “the core cities, to a host of newer, previously marginal locations.”

In a recent interview, Kotkin told TRD he actually excludes Manhattan from that general rule because of its attractiveness to the super wealthy.

Others also argue that even if people can work from anywhere, they will still want to live in cities because they want to see other people, go to concerts, go to sporting events and partake in other forms of entertainment. The Brooklyn boom of the past decade speaks to that notion.

Sam Staley, an urban planner and director of the DeVoe L. Moore Center at Florida State University, argues that the ability to work from home and communicate via the internet “in a way makes cities like Manhattan more attractive” because people have more free time and more inclination to take part in recreational activities a city has to offer.

But in this reporter’s view, this argument doesn’t square with the potential for dramatic improvements in transportation technology. What if you could have all the benefits of living in the city without actually living in it? What if — to take an extreme example — you could travel with a flying Uber from your home in Peekskill to Madison Square Garden in 10 minutes?

I get that this theory might go against the grain. But think about it: The reason New Yorkers pay $3,000 per month for an East Village studio is because we want to be a short commute from work, friends, bars and Broadway shows. It’s really the limitations of transportation that prompt everyone to pay a premium. And this isn’t just about the monthly rent bill. When we pay $8 for a beer or $4 for a granola bar, much of this goes to pay storefront rents, which are high because owners want to be close to their customers, which goes back to the limits on transportation.

But what if those limitations on transportation ease? Take self-driving cars.

Technology proponents argue that self-driving cars will make commutes easier and more efficient, allowing people to live farther from work.

Kotkin said these changes are already impacting cities on a modest scale.

“Things like Uber and Lift and other improvements in dispersed transportation systems allow people to live more remotely without the inconvenience,” he said.

But these changes are likely to only be the beginning. Uber and Google have begun studying the feasibility of flying cars. High-speed trains are spreading in other countries. Amazon is using drones for package deliveries.

Many of these innovations are untested, and no one knows for sure what the future of transportation will be like. There are undoubtedly big hurdles, such as inadequate infrastructure and government regulations (and gridlock). But it looks increasingly plausible that transportation will improve dramatically in future decades, lifting many of the restrictions that tie us to scarce and expensive urban real estate.

These changes — along with a potential construction revolution — could cause the rents we pay for housing and office space to massively shrink.

Whether they will go the way of British land prices in the 19th century remains to be seen. But it’s fun to think about.