Gowanus, a neighborhood teetering on the edge of gentrification, is getting a second shot at redemption. Six years after a rezoning plan was torpedoed by the federal designation of the Gowanus Canal as a toxic Superfund site, the city in August announced that the Department of Planning would initiate a study on the neighborhood for a possible rezoning. In doing so, Gowanus will join East Harlem, East New York and Long Island City as areas targeted for rezoning under the city’s affordable-housing strategy.

For many real estate observers, it’s a no-brainer. Surrounded on three sides by the leafy brownstone Brooklyn neighborhoods of Park Slope, Carroll Gardens and Boerum Hill, the waterfront area has long been pegged to be the next Dumbo. Between 2007 and 2015, median home sales prices rose to $720,000 from $535,335 — a nearly 35 percent jump. And in what might be the biggest sign of a neighborhood on the rise, residents in 2013 celebrated the grand opening of a Whole Foods supermarket. More recently, in April, the shared-workspace provider Coworkrs opened a 42,000-square-foot location at 92 Third Avenue, a former industrial building renovated by Dumbo Heights collaborator LIVWRK. And in another positive sign, the neighborhood boasts a total of 800 hotel rooms, according to the Commercial Observer.

Big-name investors, including SL Green, Hudson Companies, Two Trees, Kushner Companies, Lightstone Group and Kevin Maloney have already arrived. Yet with the impending rezoning, some believe that the floodgates will now open.

“There’s a lot of speculation by developers who believe they’ll be able to do things you can’t do now,” said Dan Marks, a partner at the Brooklyn-based investment sales brokerage TerraCRG.

But the environmental reality that deterred development in 2010 still exists: The most coveted land in Gowanus, which sits around the waterfront, is also the most polluted. And the scope of the federal government’s cleanup is yet to be determined. It’s possible that investigation into the site could reveal the need to extend the cleanup to areas further from the canal itself.

But the environmental reality that deterred development in 2010 still exists: The most coveted land in Gowanus, which sits around the waterfront, is also the most polluted. And the scope of the federal government’s cleanup is yet to be determined. It’s possible that investigation into the site could reveal the need to extend the cleanup to areas further from the canal itself.

Back in 2009, Toll Brothers initially secured a spot rezoning of two sites along the canal and submitted plans to build 450 condominiums. The developer, which had a contract to buy the two parcels for $20.6 million, eventually dropped the project after the Superfund site designation.

“I think the issue is that a lot of people were more afraid of the cleanup than they really needed to be,” said Lightstone Group president Mitchell Hochberg.

In 2013, Lightstone revived the housing plan started by Toll Brothers, snapping up the sites for $25.95 million. The company sold half of the project to the New Jersey-based Atlantic Realty Development for $75 million and went on to build a 450-unit apartment building at 365 Bond Street. After launching in March, the building is 70 percent leased, with rents starting around $2,500 for studios and in the low $5,000s for two-bedrooms. The complex includes not only a boat launch on the canal, but space for the local canoe club to store its boats.

“The fast pace of leasing [at the building] proves the current condition of the canal is in no way an impediment to residential development,” Hochberg said.

Yet even with changing perceptions, brokers noted that marketing efforts in Gowanus have steered clear of mentioning the infamous waterway. “I think you’d be hard-pressed to find any new development being advertised as close to the canal,” said Aleksandra Scepanovic, founder of the Brooklyn residential brokerage Ideal Properties Group. “It’s just not, from a marketing perspective, a proven way to go.”

The other looming question is exactly how much of Gowanus will be zoned residential. While newcomers have certainly entered the fray in recent years, business owners who bought properties decades ago still own significant portfolios in Gowanus, and have been reluctant to sell. “The area really has a sentimental value to them, and they want some portions of it to remain fairly industrial,” said Michael Bushkanets, an investment sales broker with Prince Realty Advisors.

Paul Basile, who sits on the board of the Alliance, a group dedicated to preserving jobs and commerce in the area, owns a pair of large warehouses at 112 12th Street and is among the landlords concerned with preserving the neighborhood’s commercial character. “I’m not against rezoning in some areas. There are parts of Gowanus that could become residential, but I don’t think the magnitude of what we hear being proposed is necessary,” he said.

Stakeholders last year put together a study concluding that residents are in favor of more housing as long as some units are set aside for low- and middle-income tenants and space is preserved for manufacturing and arts.

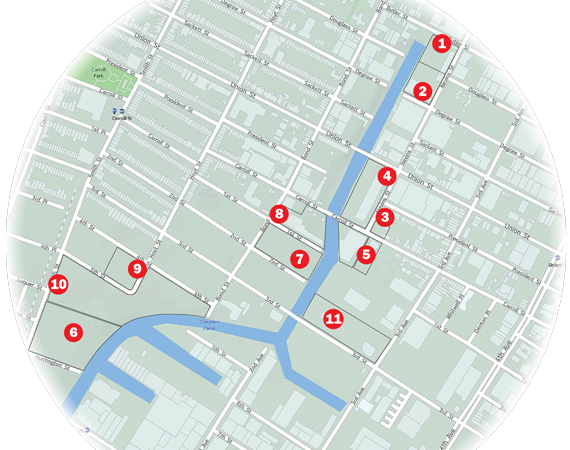

Several large residential projects are in the works or planned, including Atlantic Realty’s 268-unit building at 363 Bond Street, the site it acquired in the aforementioned deal with Lightstone. Plans call for Hudson Companies to begin work in 2018 on Gowanus Green, a long-stalled, 774-unit development.

Among the big developers, Kevin Maloney’s Property Markets Group has shelled out $73 million over the last four years for development sites near the canal such as 300 Nevins Street, a two-block-wide site fronting 450 feet on the canal. The company, which is developing the Billionaires’ Row condo project 111 West 57th Street with JDS Development, also went into contract in July to buy a large site for $50 million at 455 Smith Street.

“The turnover rate has really only started in the past couple of years,” Bushkanets said. “Before that, the major developers hadn’t really gotten a foothold.”

But looking ahead, the most talked-about and potentially the most game-changing development to hit Gowanus will be the Environmental Protection Agency’s $506 million cleanup, which will involve dredging toxic sludge, also known as “black mayonnaise,” from the bed of the canal. Work is expected to start in 2018 and will last at least five years. Thanks to longstanding zoning regulations, any development along waterfront such as the canal is required to include public access areas. So by the time the canal cleanup is complete there will be esplanades in place, such as the one Lightstone has completed at its development.

A.J. Pires, the president of Dumbo-based Alloy Development, who is planning to develop a pair of sites at the upper end of the canal into industrial/commercial spaces, said that you can get a view of the changing neighborhood if you get in a boat and paddle down the canal.

That is, he added, “If you’re brave enough.”