During the dark days of the credit crisis, New York developers discovered something of a silver bullet in a little-known U.S. immigration program.

During the dark days of the credit crisis, New York developers discovered something of a silver bullet in a little-known U.S. immigration program.

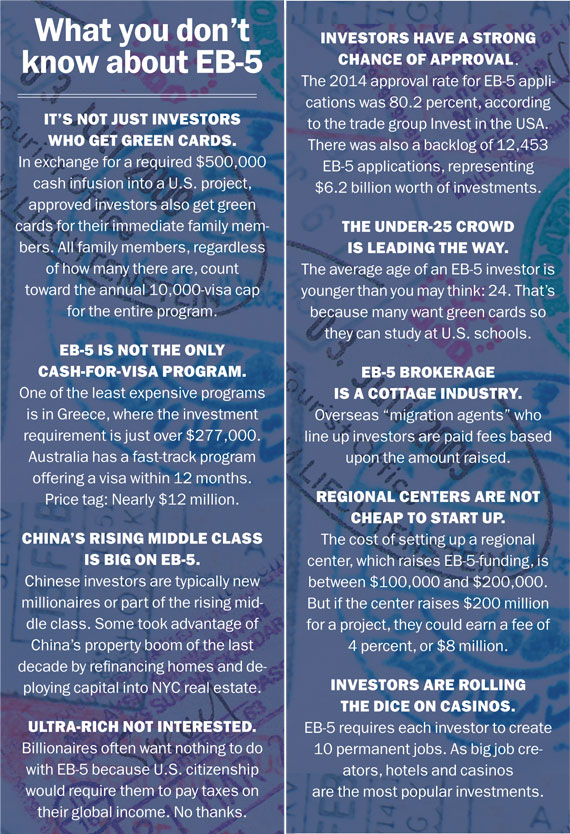

Now wildly popular and well-publicized, the EB-5 program offers a green card and potential citizenship to foreign investors in exchange for economic investment in the U.S.

In New York, developers have used the program to finance high-profile projects like the Hudson Yards redevelopment and 701 Seventh Avenue, where developer Steve Witkoff and others are building a 39-story, mixed-used tower to be anchored by Ian Schrager’s Marriott Edition hotel.

But after reeling in developers with the promise of cheap — and seemingly endless — capital, sources said the EB-5 visa program is now at a crossroads.

“We had this boom period, and that corresponded with the rise of Chinese investment,” said attorney Joel Rothstein, a partner in Paul Hastings’ real estate and structured finance department. “Now, we’ve reached the balloon-bursting point in some respects.”

Last year, for the first time since its inception in the 1990s, the EB-5 program allocated 10,000 visas, the maximum allowed. And interest is only rising: Investors filed 10,928 EB-5 applications with the U.S. government in fiscal year 2014, up from 6,346 a year prior and just 1,258 in 2008.

While numbers are hard to come by, more than $3.7 billion in EB-5 money has flowed into several dozen New York City projects over the past several years, according to an analysis by The Real Deal, using publicly available information as well as data compiled for an academic paper by a New York University professor.

Ironically, unprecedented demand for EB-5, particularly among Chinese investors seeking U.S. citizenship, has saddled the process with delays and increased competition to attract investors, which has turned some developers off to the program (see related story on page 56).

But on May 1, the federal government imposed a waiting list for EB-5 investors from China seeking green cards.

While the waiting list could dampen investor interest in the long term, the immediate impact has been loan terms that some say are riskier for developers.

On top of that, China’s economic slowdown and the government’s crackdown on corruption could “absolutely” impact investment in EB-5, said Nick Mastroianni II, CEO of the U.S. Immigration Fund, a Miami-based regional center that specializes in EB-5 fundraising and has worked with major New York developers.

“The government has changed its philosophy a few times over the last five, six years and every time they do it affects the market,” he said during a panel discussion at TRD’s New Development Showcase & Forum last month.

Meanwhile, the program is up for Congressional renewal in September, placing more pressure on developers to squeeze as much funding as possible out of EB-5 now, since no one knows if, or how, the program will be modified in the fall.

In particular, Congress could change the rules pertaining to where projects may be built. Current rules say developments supported by EB-5 capital must be in areas with high unemployment. In New York City, developers have worked around that and managed to build in wealthy areas by cobbling together census tracts. But that practice could be curtailed.

“The reality is, as we get closer to August and September, the fundraising will kind of trickle down,” said Mark Edelstein, chair of the real estate finance practice at the law firm Morrison Foerster. “If you’re starting now with a new deal, it’s dicey,” he said. “We’ve been telling clients, ‘If you can’t get into the market by July 1, just wait.’”

No panacea, but close

To date, the Related Companies has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of EB-5 in New York and nationally. The company has raised more than $800 million from approximately 1,600 investors and controls one-third of the EB-5 market nationwide.

Related raised a record $600 million for its Hudson Yards project alone: That translates roughly to 1,200 investors chipping in $500,000 each (the minimum amount required by each investor). It’s unclear exactly how many jobs will ultimately be created, but the EB-5 program requires each investor to create 10 permanent jobs.

Related continues to be bullish on EB-5’s future.

“We find this program to be a tremendous program for the U.S., in terms of job creation and in terms of allowing investments to proceed at a pace that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to,” said CEO Jeff Blau during a forum in April hosted by the China General Chamber of Commerce at business news and data firm Bloomberg headquarters. But speaking alongside Blau at the event, Extell Development’s Gary Barnett — who raised $75 million in 2011 for the International Gem Tower, a commercial condo at 50 West 47th Street — offered a more tepid assessment of the program.

“It’s not quite as simple as it seems,” he said. Investors’ “primary focus is to be able to get legal residency in the U.S., but they absolutely want to get paid back … I’m concerned that there will be some stories where people don’t get paid back.”

While Barnett didn’t elaborate on why, investors could easily lose their cash if the market turns or if a development falls through.

While Barnett didn’t elaborate on why, investors could easily lose their cash if the market turns or if a development falls through.

Generally speaking, EB-5 loans have five-year terms, since it takes that long for investors to wend their way through the immigration process. Also, depending on the project’s capital stack, the developer may need to pay the senior lender first.

Investors are only paid after their permanent green card is approved, said EB-5 attorney Kate Kalmykov of Greenberg Traurig. “But,” she added, “the law specifies that the amount of repayment cannot be guaranteed.”

Uncertain capital for cheap

A small program at first, EB-5 investment took off in 2009 when other lenders pulled back amid the financial downturn.

At this point, the program has gained so much popularity that some say it’s becoming a victim of its own success.

There are now more investors who want to get in on the action than there are opportunities, creating aggressive competition and frustration. Many have rushed to file paperwork for their visas, since green cards are processed on a first-come, first-served basis.

As a funding vehicle, EB-5 has always been a double-edged sword. On the one hand, developers pay much lower interest rates than they would on a conventional loan. On the other, raising money can be arduous and riddled with bureaucracy, uncertainty and expenses like paying immigration agents and so-called regional centers, which spearhead fundraising operations.

Some big developers have created their own regional centers to funnel investments to their projects. Others use designated regional centers to raise money. In recent years, such centers have become a booming cottage industry.

Yet, noted Morrison Foerster’s Edelstein, “There is no regional center that will guarantee how successful the raise is.” He added: “There are all sorts of stories about [trying to] raise $80 million and only being able to raise $50 million.”

Even the terms of EB-5 loans , five years or more, can turn out to be a positive or a negative, depending on how the cards fall in the market and on a project’s construction schedule.

Asaf Shuster, vice president of business development for Victor Group, said most developers don’t need the loan for five years. “You need it for two and a half, maybe three,” said Shuster.

On the flip side, he pointed out, the five-year term can be a safety net for a developer whose project is delayed, since they’re locked into low interest rates.

Shuster’s firm has raised $22 million from EB-5 investors for the Charles, a condo building on First Avenue at 73rd Street, where a unit is now in contract for $37.9 million. (The developer also obtained a $157 million construction loan.) The Victor Group is now raising $90 million for a condominium project at 281 Fifth Avenue.

EB-5 in overdrive

Despite EB-5’s uncertain future, demand from both investors and developers has not slowed. The reason? While capital is readily available, especially to New York developers, EB-5 money is far cheaper than what traditional banks offer.

Sources said that for large-scale construction projects in New York, developers might pay 10 to 15 percent interest on a mezzanine loan — the layer of capital between the senior debt and developers’ equity — but only 6 to 8 percent on an EB-5 loan.

Justin Gardinier, a managing director at the financial services firm Greystone, said that despite the availability of capital, there’s ample room for EB-5 in the market. Even if a developer obtains a construction loan, non-recourse financing — in which the loan is secured by collateral but the borrower is not personally liable — typically tops out at 65 to 70 percent of a project’s capital stack, he said.

Justin Gardinier, a managing director at the financial services firm Greystone, said that despite the availability of capital, there’s ample room for EB-5 in the market. Even if a developer obtains a construction loan, non-recourse financing — in which the loan is secured by collateral but the borrower is not personally liable — typically tops out at 65 to 70 percent of a project’s capital stack, he said.

“Any higher than that, you’re stepping into a higher rate or you’re providing some level of recourse,” he said.

That’s where EB-5 comes into play, said Gardinier, who joined Greystone in February to build up the firm’s EB-5 business. He said developers are using EB-5 dollars to offset the equity they otherwise would need to chip in to cover the balance of the construction costs.

“EB-5 is used to simply enhance the overall returns to the developer and reduce exposure,” he said. Theoretically, a developer who needs to put in 35 percent equity could tap EB-5 to lessen their loan and still retain ownership of the whole project, he said.

Steve Polivy, chair of the economic development and incentives practice at the law firm Akerman, said the current EB-5 market favors large projects, as well as projects that, for one reason or another, have difficulty attracting a conventional loan.

“The [New York] Wheel was financed with EB-5 funding because no one knows how to analyze that project for conventional bank

financing,” said Polivy, whose firm represented Plaza Capital in the Staten Island project’s fundraising. Empire Outlets, the neighborhood’s mall, “was financed with EB-5 because at the time we were looking to start construction, we didn’t have all of the leasing commitments a conventional lender would be looking to see.”

Assessing risk

The biggest issue developers have is just how long the process can take. And in recent months, it’s taken even longer than usual for developers to get their hands on funds because of the logjam of applications and concerns about potential changes to the law.

The delays have altered the way loans are structured.

Typically, investor funds have been placed in escrow as a safeguard to both the developer and investor, and released once the EB-5 application was approved. Now, some loans have “early release” provisions, meaning the developer can access the capital before the investor’s application is approved.

“It’s one thing for the money to sit in escrow for six months. It’s another if it’s sitting in escrow not doing anything for 18 months,” said Julia Park, managing director of the Manhattan-based Advantage America New York Regional Center, explaining the reason for early release.

But removing the money exposes both sides to risk. “Developers may have access to the money earlier, but they have to provide assurances that the money can be refunded,” Paul Hastings’ Rothstein said.

For example, the government could reject an investor’s application — some investors are rejected if they cannot document a lawful source of the funds. If that happens, the developer must return the money, and may face an 11th-hour funding shortfall.

“The bank never calls and says, ‘Our source of funds for the money was an investor and the investor had a change in circumstances and you need to give the money back,’” said Polivy.

Tawan Davis, chief investment officer of the Peebles Corporation and president and COO of Peebles Capital Partners, argued that although EB-5 financing was attractive during the credit crunch, it’s no longer economically compelling. “It’s not free money,” said Davis.

He said Peebles, which has $3.5 billion worth of active developments nationally, considered EB-5 financing for all of its projects over the past three years — rejecting it every time.

In the past year in particular, Davis said he’s seen EB-5 interest rates and fees creep up. Plus, he said, traditional lenders who wouldn’t cover more than 50 percent of a project’s cost during the recession are now willing to cover up to 60 percent or 70 percent. Most EB-5 lenders won’t go higher.

“If you add in the fees and you add that to the interest rate, the cost of capital for an EB-5 loan becomes more or less the same as a more traditional bank loan,” he said. “It’s actually more economical many times, and we have a better certainty of executing [development plans] with traditional financing.”

To that end, Davis said EB-5 doesn’t have the certainty of traditional institutional lenders.

“I can’t show up to the groundbreaking without the certainty that on a $400 million project, my debt financing is in place,” he said. For a project of that size, he said you’re talking about several hundred investors. “Many times, it’s just too big of an ask,” he said.

Change underfoot

The EB-5 community expects changes to the program in September, when EB-5 comes up for renewal. For example, some believe the minimum investment of $500,000 could be raised to $800,000.

Lily Guo, president of the Flushing-based American Regional Center for Entrepreneurs, predicted that delays and heightened competition would inflate costs for developers in the long-term. Approved in 2013, the American Regional Center has worked on lining up investors for six projects to date, including the Oosten in Williamsburg.

With hundreds of regional centers to choose from, Guo said investors may start shopping around for more competitive returns.

Typically, EB-5 investors receive 0.5 percent interest on their investment, according to attorney Gary Friedland, who co-authored a paper on EB-5 financing with a New York University professor.

Greenberg Traurig’s Kalmykov said she’s seeing deals get done with higher interest rates, a function of a more sophisticated market.

“It has become a cottage industry,” she said, “where brokers take significant fees for raising funds.”

But Guo said she is seeing investors hungry for more. “We have seen investors saying, ‘It’s not worth it. I’m not happy with the return just for a green card.’”