UPDATED, Feb. 5, 11:38 a.m.: Just 20 years ago, fax machines were in wide use and most people didn’t have cell phones. Fast forward to today, and smartphones are inescapable and personal hotspots are tucked into everyone’s pockets.

The real estate industry has seen its own advances during that time, with drones debuting on construction sites and prefabricated modular apartments now being snapped together easily onsite.

Today, for example, it’s virtually impossible to ignore the white-hot Bitcoin craze and barrage of news about how cryptocurrencies and blockchain could revolutionize real estate.

But the next big tech revolution in New York’s trillion-dollar real estate business could be far more disruptive. In the near future, the industry could see smart buildings fully controlled by technology, robots taking the place of construction workers and New York City skyscrapers being made by 3D printers. Meanwhile, property leases, loans and investment transactions may be handled without any human involvement, observers say, thanks to artificial intelligence.

The question everyone is now mulling: After decades of sparse innovation, is real estate finally in for a major wakeup call from the tech sphere?

“I only see the pace of change accelerating,” said James Barrett, chief innovation officer at Turner Construction, one of the largest construction management firms in the country.

This month, on the heels of the bustling CES tech conference in Las Vegas, The Real Deal broke down some of the innovations with the greatest potential to upend the real estate industry — from artificial intelligence and virtual reality to people-tracking beacons and blockchain.

Some are already having an impact on the industry, while others are still in their infancy.

And these technologies are benefiting from a flood of venture funding. Between 2012 and 2017 alone, AI startups raised $18.74 billion in venture funding, according to research firm PitchBook. Robotics and drone companies raised $3.95 billion, 3D printing startups raised $1.58 billion, blockchain startups raised $1.78 billion and virtual reality companies raised $4.66 billion.

While the bulk of that money did not go to real estate companies, the technologies are now starting to creep into the industry.

“We’re absolutely on the cusp of a paradigm shift,” said Chris Kelly, co-founder of the tech-focused office services firm Convene, which has raised $119.2 million in venture funding since 2009.

“We’re absolutely on the cusp of a paradigm shift,” said Chris Kelly, co-founder of the tech-focused office services firm Convene, which has raised $119.2 million in venture funding since 2009.

“Real estate is the largest class on the planet and among the least changed by technology,” Kelly added. “Anyone who can see straight has to realize this will change.”

Boosting artificial intelligence

Welcome to the world of AI. Last March, the online asset manager AlphaFlow launched its first so-called automated investment fund for real estate loans.

Rather than tapping employees to search for investment opportunities, the company uses a computer program to sift through listings services and find mortgages to purchase based on property characteristics, borrower history, recent market data and other criteria.

“We’re not ready to take our hands off [our work],” said Ray Sturm, co-founder of the California-based company, explaining that humans still make the ultimate investment decision.

But, he noted, machine-driven algorithms are doing increasingly more. And a growing cohort of AI-powered companies — including AlphaFlow, Ten-X and Opendoor — is starting to transform real estate investment and brokerage much like passive investment funds revolutionized the stock market in the 1980s.

In its most basic form, AI has been around for decades. But the technology has gone through a recent growth spurt, most notably with machines now more capable of “learning,” meaning they can perform tasks without being programmed to do so.

Ten-X, which has raised $141.8 million in funding, per Crunchbase, and was acquired by private equity firm Thomas H. Lee Partners last year, created its own algorithm to match investors with properties, for instance. The system analyzes investment sales data to determine which properties certain investors tend to buy. It then picks buildings that match their criteria on its site and recommends them.

Ten-X’s Neelika Choudhury, vice president of product strategy and product marketing, said the algorithm creates better, faster and cheaper leads than humans could. But it requires regular maintenance to keep up with investor behavior.

“If we don’t constantly refine our training data, the model won’t work,” Choudhury said.

Meanwhile, California-based Opendoor, which was founded in 2014 and has raised a massive $320 million, buys single-family homes with the help of machine-learning algorithms that identify investment opportunities and determine the price (although sellers generally approach Opendoor first). It then puts those properties up for sale online.

Commercial and rental lease management firms are also turning to AI. Startups like Leverton and Counselytics sell software that sifts through lease contracts, extracts information and even makes decisions.

“It saves an immense amount of time,” said Zach Aarons, an executive at the real estate investment firm Millennium Partners and co-founder of the New York-based tech accelerator and advisory firm MetaProp NYC.

But even Aarons seems to think lease abstraction may not be ready for prime time — at least in the complex New York market. Millennium considered using it, he said, but ultimately decided against it, partly because it was concerned about errors.

But even Aarons seems to think lease abstraction may not be ready for prime time — at least in the complex New York market. Millennium considered using it, he said, but ultimately decided against it, partly because it was concerned about errors.

“Some of our leases are so complicated we’re not even sure humans would get it right the first time,” he said.

And while AI has yet to infiltrate the construction sector, sources say it’s only a matter of time.

Turner’s Barrett said AI could revolutionize construction by automating the design process, cost calculations and scheduling. While he declined to offer specifics, Barrett said Turner is researching machine-learning technology.

The applications for it in construction abound.

Ardalan Khosrowpour, a New York-based entrepreneur, recently launched OnSiteIQ, which creates 360-degree images of construction sites to track progress and potential hazards. The startup is working on machine learning software that will automatically analyze the images to spot potential safety hazards or other problems.

Khosrowpour said he’s now in talks with several major development firms, which he declined to name. “Machine learning will be the future,” he said. “I have no doubt about it.”

How bright are smart buildings?

Every time a tenant enters or exits a Rudin Management-owned property, the building notices. A sensor in a turnstile near the entrance sends a signal to the property’s operating system, dubbed Nantum. The system can sense sudden shifts in occupancy and quickly adjust its heating and air-conditioning depending on the season.

Rudin launched the independent tech startup Prescriptive Data — Nantum’s creator — in June 2016. The Manhattan-based company supplies Rudin’s buildings as well as properties owned by six other landlords with its technology. (A representative for Rudin declined to name the other landlords.)

The startup seems to be at the forefront of the smart building revolution underway in commercial real estate, including rental apartments.

“Property owners are just now realizing that they need to future-proof their buildings,” said John Gilbert, Rudin’s chief technology officer and executive chairman of Prescriptive Data.

Smart building technology can also be useful in the event of a natural disaster or attack, Gilbert said, explaining that Nantum knows exactly where people are in a building as well as general movement patterns. That, he said, can help warn landlords and tenants of an “impending safety concern in real time and can help emergency services identify the specific location of occupants.”

Following Rudin’s lead, Convene is now working on a building operating system that uses beacon technology (see below). The firm, which manages common spaces and amenities as well as co-working spaces, is currently beta-testing its system in two office buildings. One of those is owned by Brookfield Properties and the other by the Blackstone Group, Kelly said. With the help of beacons, the building’s operating system can automatically change a room’s temperature and lighting or even order a cup of coffee depending on who walks in.

The smart buildings of the future, Kelly and other sources said, will be akin to giant computers run by even more advanced operating systems that increasingly rely on machine learning.

Smart building technology is also being enabled by a new wave of home automation products such as Google’s Home and Amazon’s Echo. The voice-recognition gadgets allow consumers to control their music, entertainment and shopping whims from anywhere in their home.

Firms like Nest, which Google acquired for $3.2 billion in 2014, produce smart thermostats, while others like Latch and Teman, which makes GateGuard.xyz, sell smart door technologies: screens that recognize faces and let customers open and close doors from virtually anywhere on their phones, in some cases with the help of Wi-Fi. And the list goes on.

“A building manager goes home and talks to his Alexa and has a really great software experience with five or six different mobile apps during the day,” said Luke Schoenfelder, co-founder of Latch, which has raised $26 million since it launched in 2014 and markets its products to multifamily property owners. “Then they get to their office, and all the systems haven’t changed in 20 years.”

The proliferation of home automation products has rapidly increased the need for operating systems in large commercial properties, argued Gilbert. Hotels are also waking up to the trend.

For example, Verdigris, which sells technology that monitors a building’s energy usage, counts Hyatt, InterContinental and W Hotels among its clients.

Technologies like Latch produce data, but landlords can’t effectively use that data unless they’re properly wired to a central system.

While costs of these systems vary and are tricky to pin down, Gilbert said Rudin’s Nantum system has saved the development firm about $5.5 million a year in heating, electricity and maintenance expenses.

Smart technology can also help reduce disturbances by tracking elevator usage and estimating when repairs are needed. “I don’t think about it as the future,” said GateGuard creator Ari Teman, speaking about smart buildings generally. “It’s happening right now.”

Smart technology can also help reduce disturbances by tracking elevator usage and estimating when repairs are needed. “I don’t think about it as the future,” said GateGuard creator Ari Teman, speaking about smart buildings generally. “It’s happening right now.”

But while the idea of responsive buildings may sound like a no-brainer for owners, there are obstacles.

Arie Barendrecht, co-founder of WiredScore — which grades buildings’ connectivity and tech infrastructure — said that only about 20 percent of New York office buildings have the high-speed internet wiring needed to sustain smart buildings. In addition, it’s a big upfront financial investment for landlords — especially if they invested heavily in their properties.

“[It’s] never an easy shift,” Barendrecht said. “If you’re a building owner, there’s obvious hesitation to completely cede human intervention.”

The cold, hard virtual reality

About six months ago, a team of architects at Perkins+Will met with executives from a major health care company to discuss the design of new medical exam rooms. The architects suggested a tweak to the planned design, but the client balked.

Historically, that interaction would likely have ended with the architects going back to the drawing board, said Iffat Mai, the firm’s digital practice manager. But in this case, the architects handed the client a virtual reality headset.

After “walking” through the redesigned space, the client signed on for the proposed changes, according to Mai, who called virtual reality a “game changer” for real estate.

“Over the past 24 months, virtual reality and augmented reality just kind of exploded and became readily available and affordable,” said Mai, noting that Perkins+Will began researching the technology about five years ago.

Today the company has its own VR software, which it uses as a more realistic substitute for drawings and to show clients what a space may look like.

VR’s big breakthrough came in March 2016, when Facebook-owned Oculus Rift released its first headset to the mass market for $599. Since then, the technology has become a staple in luxury condo sales galleries. New developments traditionally had a major disadvantage: Buyers couldn’t physically walk through apartments that weren’t yet built. VR solves that issue, and developers are increasingly relying on software to sell units.

And now both VR and AR are starting to seep into the construction industry. Turner Construction created its own AR software, which gives project managers hands-free access to their documents while they’re on-site, Barrett said. (AR goggles show users their actual surroundings, overlaid with computer-generated renderings or even their emails.)

Barrett estimated that Turner invested between $75,000 and $100,000 in the technology in 2011 and 2012 , in part because VR headsets were more expensive back then. More recently, the company spent about $50,000 to create virtual models of a New Jersey cancer clinic the company was building. The investment pays off — at a return-on-investment ratio of about 10 to 1 — because the client is better aware of what the space will look like and is less likely to request late, costly changes, he said.

“It’s a no-brainer,” he added. “Solving problems virtually long before they might become reality is a far better, cheaper alternative to traditional practices.”

And there are plenty of startups betting on the profitability of just that.

Matterport, a California-based startup backed by $66 million in venture funding, is building VR technology for construction projects. Like OnSiteIQ, its devices capture 360-degree, 3D images of construction sites that can be accessed remotely using VR headsets.

The firm’s director of architecture, engineering and construction, John Chwalibog, described the technology as an asset in today’s international real estate market.

“A lot of product and design teams are global now,” he said. “The project is in New York. An engineer might be in San Diego, an owner might be in Melbourne. Everyone can get together and do that virtual walk-through.”

But VR has been slower to take hold in the office leasing market.

In 2011 and 2012, two startups, View the Space and Floored, launched to great fanfare. Floored offered 3D visualizations, and View the Space created video tours of office buildings — two products that seemed destined for VR devices. But View the Space (which ultimately changed its name to VTS) successfully shifted its focus to offering online portfolio and lease management software. And Floored was acquired by CBRE and folded into the brokerage’s data and technology division in 2017.

“A few years ago VR was all the rage, and now you rarely hear about it anymore,” said Ash Zandieh, founder of the real estate tech research and consulting company RE:Tech.

VTS co-founder Nick Romito said he is “baffled” by the slow pace at which VR and AR are spreading across the office leasing industry.

“If you would have asked me three years ago, I would have said the next generation of our industry is … anything virtual,” he said. “But it almost feels like we’ve kind of taken a step backwards.”

Romito speculated that the slippage might be a product of the marketing, which has largely been targeted at brokers and landlords rather than to the potential tenants, who might see the most use.

MetaProp’s Aarons argued that AR and VR have yet to fully take off because the devices and software still tend to be expensive.

But that could soon change. The price of an Oculus Rift headset has already dropped to $399 from $599. “There’s some magic price. I don’t know what it is, but we’re close to hitting it,” Aarons said. “It will explode on the marketing side.”

The construction robots are coming!

A remote-controlled demolition robot knocking down New York City structures in broad daylight might sound like the stuff of science fiction, but it happened just a few weeks ago at the corner of 33rd Street and 10th Avenue. And it was done to make way for Related Companies’ 30 Hudson Yards.

The machine’s creator is Brokk — a 35-year-old company based near Seattle that manufactures remote-controlled demolition machines traditionally used in the mining industry. And it was employed by AECOM Tishman, the general contractor on the 90-story office tower project. AECOM has a robotics task force that identifies usable technology and brings it to its sites, said Michael Lorenzo, the firm’s director of emerging technologies.

Still, so far construction workers donning hard hats have little to worry about in New York, where these construction robots are still rare.

But a few startups are looking to bring more robots to the construction industry.

Barrett said his firm has had talks with the architectural tech consultancy Asmbld about mobile robots that paint walls and pour concrete and is considering investing in joint research and design. But, as of now, the construction giant isn’t using any of the machines on its projects.

“We’re cautious about introducing robots into our job sites because you really have to design your work to that,” Barrett said, explaining that robots could disrupt workflows.

Lorenzo argued that construction robots will only really take off when they’re equipped with AI and can safely navigate construction sites. “Once we get to the point where robots are able to analyze a situation and actually see what’s in front of them, that’s probably when we’ll have robots on the job site,” he said.

“At this point in time it’s really very much path-driven robotics where one robot is used for demo, one robot is used for bricklaying, et cetera,” Lorenzo added.

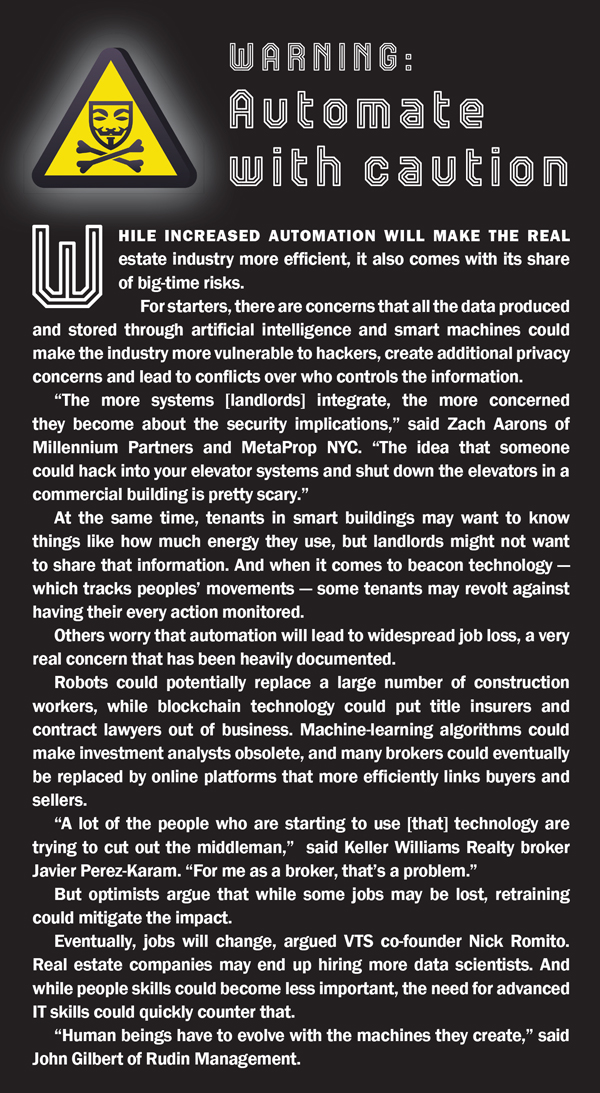

The deeper concern for the construction industry — not to mention for the broader economy and workforce — is what smarter robots would mean for employment.

PricewaterhouseCoopers recently estimated that 38 percent of all U.S. jobs are at risk of being lost to automation by 2030 — a glaring statistic with serious implications for real estate. And, according to a recent report by the public policy think tank Center for an Urban Future, painting, construction and maintenance has the sixth-highest potential for automation among 25 major occupations in New York.

Jose Cruz, director of virtual design and construction at the construction services firm UA Builders Group, predicted that in the coming decade the construction industry will see more machines doing repetitive tasks, such as laying bricks, at sites that are still overseen by human workers. New York-based Construction Robotics already produces the bricklaying robot dubbed SAM100 (short for semiautonomous mason), which has a robotic arm that takes bricks from a tray, applies mortar and places them on a wall without human involvement.)

“I think right now construction robotics is in its nascent stages.” Cruz said.

3D printing future skylines

When 3D printing was invented in Japan in the early 1980s, it was churning out small objects like cups. Then in the 2000s, the technology garnered international buzz when it was used to print firearms, prosthetic limbs and eventually even houses.

Now, some say, it could soon be used to create entire office towers.

“[3D printing is] the most disruptive technology we have in real estate, because you have companies coming out that can print full-blown structures within minutes with no human labor whatsoever,” Aarons said, predicting that within 20 years the technology will be able to create Manhattan skyscrapers at 20 to 30 percent of what it currently costs to build one.

Others are bullish, too.

In January, the industry research firm SmarTech Publishing estimated that real estate 3D printing could generate $4 billion in annual revenues by 2027.

In March, the California-based startup Apis Cor made headlines when it printed an entire single-family home in Russia in 24 hours using a mobile 3D printer that looks a bit like a construction crane. The printer processes design plans and pours concrete walls and floors with virtually no human involvement, and workers then install windows and doors to finish the home.

Another startup, the Tennessee-based 3D printing company Branch Technology, recently won the first prize in a NASA competition to develop technologies to build homes on other planets without human labor. The competition was part of NASA’s Centennial Challenge program, which looks for solutions to the technical challenges of operating in outer space.

And in 2015, Shanghai-based WinSun reportedly printed a six-story apartment building. Last March, the company announced that it had agreed to lease 100 3D printers to the Saudi construction firm Al Mobty Contracting in a deal it claimed was worth $1.5 billion. In May, WinSun even ventured into U.S. politics, jokingly offering to build President Trump’s planned border wall.

“Donald Trump could build his wall much cheaper and in less than a year,” founder Ma Yihe told the South China Morning Post. “We could definitely do it. Maybe at around 60 percent of the projected cost and three to four times faster.”

Still, it may be a while before 3D printing takes over construction in the Big Apple. Some sources are skeptical that the technology can be used to build entire skyscrapers anytime soon, pointing out that it may take several more decades to make it safe, cheap and sturdy enough.

Barbara Kavovit, CEO of the New York-based firm Evergreen Construction, said 3D printing could have a major impact on the industry by making the construction of affordable housing cheaper. She estimated that it will take three to five years before the technology becomes more widely adopted.

“I think the expectations are really high, but I don’t think that it’s a reality for most of us yet,” she said, noting that obstacles such as cost, safety uncertainties, durability and resistance to change are very real.

“The construction industry is one of the most risk-averse industries and also one of the slowest in adopting new technologies,” Kavovit added.

Beacons in the night

“Location, location, location” isn’t just the real estate industry’s mantra. Google Maps and Uber don’t work unless they know where users are.

GPS “is a critical element of digital services in our lives outside of work,” said Convene’s Kelly. “There’s just one problem with GPS: It can’t see inside buildings.”

But beacons — tiny devices that can be placed almost anywhere in a room — can. And they are slowly starting to reconfigure the use of commercial real estate.

By sending out Bluetooth signals that get picked up by nearby smartphones, the technology can track who is in the room. The devices have been common in the retail business for several years — at the very least since Apple showcased its iBeacon protocol in 2013.

Retailers can use beacons to send advertisements to customers’ phones when they walk into a store. In 2015, Business Insider estimated that beacons would be responsible for $44 billion in retail sales in 2016 alone.

More recently, the technology has emerged as a key component in the smart building revolution underway in the office, hotel and residential markets. WeWork, which is now backed by more than $6 billion in venture funding, is using beacons to design its buildings more efficiently by tracking its users’ movements. The push to use beacon technology is part of WeWork’s broader strategy to turn its offices into smart buildings. The company has long employed an in-house tech team headed by David Fano and last year hired Apple veteran Shiva Rajaraman to oversee its digital products.

Beacon technology can also help office users find their way around a building, much like GPS does outside. And it allows a building manager to anticipate repair needs by tracking the use of elevators or restrooms.

With beacons, Kelly said, “everything in a building is moving from defense to offense.”

Rudin’s Gilbert echoed that point.

“If you are not gathering and mining data within your buildings, then you’re really not doing your job,” he said.

But there are obvious privacy concerns. Tenants may balk at having their every movement tracked and recorded — a Big Brother situation that’s recently haunted Facebook.

In mid-2015, the Federal Trade Commission reached a settlement with beacon technology firm Nomi Technologies following allegations that the company misled retail shoppers about their ability to opt out of its tracking system.

In a report published at the time, FTC chief technologist Ashkan Soltani said beacons create privacy issues that “are further exacerbated by the fact that most consumers are not aware that their device information may be captured as they walk by a store or visit an airport.”

Decoding the blockchain boom

In 2012, entrepreneur William Skelley co-founded iFunding, an investment platform that helped pioneer real estate crowdfunding. But the company quietly shuttered last year, while several other crowdfunding startups also fizzled.

Now Skelley is trying to shake up real estate finance again, but this time he’s betting on something else: blockchain — electronic records that are encrypted and linked across a network of computers.

Skelley recently founded the blockchain consultancy William Christopher and is advising New York developer Ruben Azrak on his real estate-based cryptocurrency, Realecoin. The digital currency launched last year, and Azrak plans to use it as a new tool to help fund his deals.

“Blockchain right now is what the World Wide Web was in the early ’90s,” said Keller Williams Realty broker Javier Perez-Karam, who has been closely following the technology. He argued that the electronic ledger — which is resistant to tampering and can expedite transactions— will completely shake up the real estate industry.

Its most famous outgrowths are cryptocurrencies that use blockchain technology to establish records of ownership and regulate currency supply without any involvement from a third party, like a bank.

As of early January, the combined value of all cryptocurrencies around the globe was at least $700 billion (that number fluctuates second by second). Bitcoin rose more than 1,600 percent in the past and hit an all-time high of $19,783 on Dec. 17 before dropping and hovering around $10,000, according to CoinDesk, which tracks major digital currencies.

Looking to tap into that wealth, at least half a dozen companies now allow investors to use cryptocurrencies to buy stakes in U.S. real estate. Azrak, for one, bought an apartment building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side for $19.4 million last year and is now making the property available to investors via Realecoin.

Azrak said the fund won’t change his investment decisions, noting that it’s merely a new way of paying for deals. “I’m going to buy whether it’s with the investors involved or not,” he said.

For the time being, using cryptocurrencies to buy real estate allows users to easily move money around from online accounts without the transaction costs of converting into dollars first. Skelley said he hopes that it will offer tax advantages as well, once regulations get ironed out.

But he acknowledged it could go the other way, and regulators could crack down on the space altogether. “That’s the biggest risk and the biggest opportunity,” Skelley said.

Some observers are skeptical that blockchain and cryptocurrencies can really make a difference in real estate. Blockchain “is still a little bit unclear,” said Mike Sroka, founder of the real estate deal management platform Dealpath, who argued that U.S. dollars have worked just fine. “Here we have a solution that is searching for a pain point.”

Cryptocurrency “introduces a lot of risk,” he added, citing the potential for a crash if regulators step in.

Other industry players are more bullish on blockchain and its potential to change everything from crafting contracts to establishing land titles. Stayawhile, an online vacation rental marketplace, is working on smart contracts backed by blockchain technology, and the rental listings site Rentberry is also using it to facilitate transactions.

Tal Kerret, president of Silverstein Properties, said he expects blockchain to be widely adopted for real estate contracts, but cautioned that change may be slow.

“It just needs to be something that people are comfortable with,” he said. “How many years did it take for people to stop using fax machines?”

Corrections: An earlier version of this story included a figure for Opendoor’s venture funding that was taken from Crunchbase but was incorrect. The right amount is $320 million. The article also incorrectly claimed that Oculus Rift was acquired by Google. Clarifications were also made to references to GateGuard.xyz and Matterport in the story.