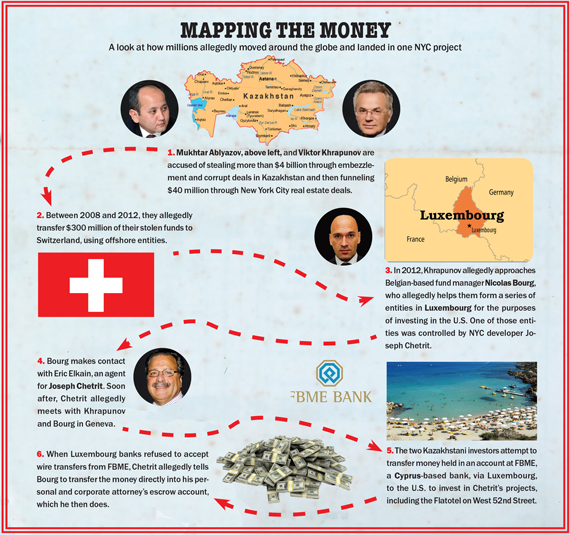

In 2012, Joseph Chetrit [TRDataCustom], a Moroccan real estate investor known for his New York City developments, allegedly flew to Geneva to meet Nicolas Bourg, a Belgium-based real estate fund manager, to talk about raising equity for several new projects.

Bourg was representing an investment fund backed with money allegedly stolen by two Kazakhstani investors — Viktor Khrapunov, the former mayor of Almaty, the largest city in Kazakhstan, and Mukhtar Ablyazov, the former chairman of the country’s BTA Bank. The two were eager to place their money in the U.S., and New York City seemed like a good bet for unloading a serious amount of cash quickly.

In order to make a deal, the Kazakhstanis offered Chetrit unusually favorable terms, agreeing to provide 75 percent of the cash needed to build the developer’s Flatotel condo project at 135 West 52nd Street for only 50 percent of the project’s profits. The difference effectively amounted to an above-market “promote fee” for Chetrit.

It was the perfect solution for the developer, but there was a catch: Between the two of them, Khrapunov and Ablyazov were facing criminal charges in Kazakhstan, the U.K. and Switzerland over allegations that they’d stolen more than $4 billion through embezzlement and corrupt deals in Kazakhstan. They had fled their home country to avoid arrest, and their assets were frozen in all three nations. In other words, the money was dirty.

According to a lawsuit brought last year against companies controlled by Chetrit and his brother, Meyer, by the city of Almaty and BTA, the developer was well aware of the situation. The suit — which spelled out all of the above-mentioned details — said Chetrit was so wary of detection that he even used code names to refer to his partners, including “Jose” and “Pedro.”

“The situation was made unequivocally clear to Chetrit,” according to the complaint, which was filed in New York’s Southern District and claimed the developer was complicit in laundering the money through New York real estate.

“Chetrit expressed sympathy with the situation, since his own family had faced political sanctions in Morocco,” Almaty and BTA claimed.

“Chetrit expressed sympathy with the situation, since his own family had faced political sanctions in Morocco,” Almaty and BTA claimed.

While the suit was settled last year — with Chetrit agreeing to cooperate with Almaty and BTA in their claims against Ablyazov and Khrapunov — the case provides a window into how illicit money is increasingly being stashed in U.S. commercial real estate and what procedures exist (or don’t) to prevent it.

In 2006, the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) identified 9,528 suspicious commercial real estate transactions in the U.S. in a 10-year period starting in 1996.

While the agency didn’t release statistics for New York City and did not return multiple requests for comment for this story, it found that suspicious activity had tripled in the next five years leading up to 2011. Half of those cases came from just five states: New York, California, Florida, Georgia and Illinois.

“It’s a systemic issue,” said Nuri Katz of Apex Capital, a Montreal-based firm that helps foreign investors get citizenship in other countries and has helped Russian investors place their money in U.S. real estate.

“You can’t blame just a bank, or a seller, or a buyer. You need to look at, federally, why is the U.S. not watching out for these things? Why is the U.S. encouraging unknown money to come in?” Katz said in an interview with The Real Deal.

Indeed, while Chetrit’s dealings with the Kazakhs read like a scene from “Catch Me If You Can,” the case is just one of many in which illicit funds are flowing into properties here.

One of the highest-profile cases involved the laundering of cash from a state-investor Malaysian economic development fund — 1Malaysia Development Bhd, or 1MDB — which prosecutors say bankrolled the Park Lane Hotel on Central Park South. The scandal rocked the financial world, ensnaring developers, major global banks, political figures and even a Hollywood actor along the way.

While the 1MDB case may be extreme, the risk of getting tangled up in shady deals seems to be on the rise. That’s partly because the temptation to turn to foreign funding sources is higher than ever for developers, as traditional financing for many condo projects has dried up amid rumblings of a potential supply glut.

Developer Sharif El-Gamal of Soho Properties, for instance, told TRD that in order to score the money to build his condo at 45 Park Place, he syndicated a deal with a network of overseas financiers that included Malaysia’s Malayan Banking Berhad, Kuwait’s Warba Bank and a Saudi investment firm led by the Al Subeaei family.

Developer Sharif El-Gamal of Soho Properties, for instance, told TRD that in order to score the money to build his condo at 45 Park Place, he syndicated a deal with a network of overseas financiers that included Malaysia’s Malayan Banking Berhad, Kuwait’s Warba Bank and a Saudi investment firm led by the Al Subeaei family.

While that deal has not been linked to money laundering in any way, it shows the extent to which foreign investors and lenders have become involved in complex transactions in New York.

“Some of the largest and most-established developers in New York City are not able to procure financing,” El-Gamal said.

As more developers look to untested investors in foreign countries for capital, it has become increasingly difficult — even for those with the best of intentions — to vet potential partners, sources said. And then there are those willing to overlook red flags in order to get a project off the ground.

“There will be people that will take money from any source that gives it to them,” said Jonathan Adelsberg, a partner at the New York-based law firm Herrick Feinstein.

Follow the money

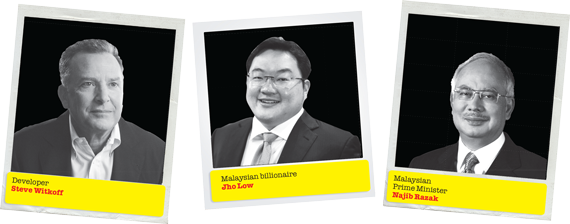

In the case of the Park Lane Hotel, even some of the city’s top real estate players and financial institutions failed to spot dirty cash from a key investor: Malaysian billionaire Jho Low

In the fall of 2009, Low suddenly bounded onto the New York party scene seemingly out of the blue.

The pudgy Wharton grad quickly caused a stir with his lavish lifestyle, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars a night at Manhattan clubs. Rows of Cadillac Escalades were often parked outside the venues he was partying in.

He also bankrolled Leonardo DiCaprio’s 2013 film, “The Wolf of Wall Street,” after meeting the actor on the nightlife scene.

For his 28th birthday, Low threw himself a four-day party at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Caged lions and tigers dotted the pool area. Actress and model Megan Fox was flown in to hang out with him, the New York Post reported on Page Six.

But questions about the source of Low’s wealth soon began to surface. Some said he was in construction, others said it was “family money.” Few asked questions, opting instead to bask in the glow of his wealth.

Like many of New York’s richest residents, Low soon began investing in real estate, providing capital to some of the city’s most active developers, including Steve Witkoff, who was seeking financing for his planned redevelopment of the Park Lane Hotel. An unnamed real estate attorney introduced the pair, and Low ultimately invested upwards of $200 million in the project, making him the majority equity investor, with an 85 percent stake, according to papers later filed in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles as part of an effort by the U.S. Department of Justice to seize Low’s stake in the building.

A rendering of the Witkoff Group’s 1 Park Lane

Together Witkoff and Low planned to knock down the aging hotel to make way for a 1,210-foot-tall, 88-unit condo tower. The project, dubbed 1 Park Lane, was set to cost $1.7 billion, with expected revenue of $2.3 billion.

But even Witkoff doesn’t appear to have uncovered the source of the young Malaysian’s fortune.

In October 2013, as Witkoff and Low finalized the terms of a deal with Wells Fargo and Criterion Real Estate Capital for $525 million in acquisition financing, a principal at the Witkoff Group emailed Low asking for details about where his capital was coming from, according to the DOJ’s court documents.

“We are getting down to the end with the lender, they are asking for specifics on where the money on your side of the deal is coming from given it is international money,” the email said.

Low responded the same day: “Low Family Capital built from our Grandparents, down to the third generation now.” The Witkoff principal replied: “Ok, thanks Jho, just didn’t know if there were any other minority investors on your side, I will let the bank know.”

In reality, the DOJ alleged that Low’s money was illegally siphoned from 1MDB into the accounts of Prime Minister Najib Razak and his associates, who included Low’s father, Larry, and brother, Szen.

Authorities say Low headed Good Star Ltd, a company that received a massive $1.03 billion from the fund. So it’s not surprising he was able to drop so much cash on real estate, art and partying in New York. He allegedly moved money between accounts in Singapore, Switzerland and New York “in a manner intended to conceal” the origin of the money.

Sources close to the deal told TRD that there were no warning signs before the Low scandal broke. Low was based in the U.S., attended meetings in New York and was one of the lead investors on Sony’s $2.2 billion purchase of EMI Music Publishing, before his deal with Witkoff. He had references from global leaders. At the time he completed the Park Lane deal, he was already in discussions with other major developers, including the Related Companies and Extell Development. “I had no clue there was anything amiss with Jho Low, but probably Steve [Witkoff] just gave him a better deal than I was ready to give him,” Extell’s Gary Barnett told TRD. “Thank God we’re not involved with that.”

Low’s ability to move such vast amounts of cash undetected speaks to the lack of oversight that’s often common on these kinds of transactions, sources said. The fact that the checks and balances that financial institutions — particularly those as large as Wells Fargo — must perform under federal law did not catch Low in the act remains unexplained.

In court documents, however, DOJ prosecutors spelled out Low’s complex maneuverings and the series of wire transfers that enabled him to move hundreds of millions of dollars through at least eight banks across the globe between March and November 2013, when Witkoff closed on the Park Lane.

On Nov. 12, 2013, Low allegedly wired more than $218 million from an account with Swiss bank BSI — later implicated in the 1MDB scandal — in Singapore to a Citibank account in New York controlled by his global law firm DLA Piper. Then, following a capital call from the developer on Nov. 20, he moved $202.2 million from the DLA Piper account to a JPMorgan account maintained by Commonwealth Land Title Insurance, the escrow agent for the Park Lane deal.

Witkoff, who has not been accused of any criminal wrongdoing, said he’s cooperating with authorities and told TRD that he and his partners had “no knowledge whatsoever” of any of Low’s alleged crimes when the two went into business together. He also said the situation would not impact his project.

“The recent actions taken by the government against Jho Low will in no way impede our ability to bring the Park Lane project to a successful conclusion,” he said.

Multiple developers and brokers, however, questioned how developers could know so little about their equity partners.

But Low was not the only one to go unnoticed after transferring massive sums.

But Low was not the only one to go unnoticed after transferring massive sums.

In the case of the Kazakhstani investors, the movement of $34 million to the Chetrits’ Flatotel and $6 million to the developer’s conversion of the Cabrini Medical Center in Gramercy was equally brazen.

The investors had stored their allegedly ill-gotten gains in an account with FBME, a Cyprus-based bank. FBME was widely understood to be a bank through which money-laundering transactions could be routed, including on behalf of drug traffickers and even members of the Islamic militant group Hezbollah, according to the complaint filed against Chetrit by Almaty and BTA. FBME was later added as a defendant in the suit.

In 2014, FinCEN designated the bank a concern and found that the institution was regularly used by customers to facilitate laundering, terrorist financing and transnational organized crime. The Kazakhs allegedly first attempted to transfer the funds through banks in Luxembourg, but the banks refused to accept wire transfers — partly because of the pending investigations. Then, Chetrit allegedly told Bourg to transfer the funds directly into an escrow account held by his personal and corporate attorneys, according to court documents. The funds were transferred May 20, 2013, directly from FBME to Chetrit’s attorneys.

Breaking the locks

While the scope of Low and the Kazakhs’ schemes are rare, sources said smaller amounts of illicit money slide into commercial real estate with relative ease regularly.

“At the end of the day, there are a lot of locks on a lot of doors, but people are still going to break through the locks and get in,” Herrick Feinstein’s Adelsberg said.

FinCEN’s analysis backs that up.

It shows that dirty money is not just a problem on high-profile deals. Most of the suspicious deals — some 45 percent — were for loans under $1 million. And just 8 percent of deals were valued at $10 million or more.

Still, it’s the high-profile cases that often drive the movement for change and have more far-reaching consequences.

The 1MDB scandal, for example, has also touched Extell’s Barnett, who partnered on his One57 condo development with Abu Dhabi-based Aabar Investments and privately held investor Tasameem Real Estate Co. (Aabar’s parent company — International Petroleum Investment — has come under scrutiny as part of the 1MDB investigation.)

Aabar’s former chief executive Mohamed al-Husseiny stepped down from his post earlier this year after allegations surfaced that he was in cahoots with Low. Sources said that both al-Husseiny and the Malaysian prime minister even provided fraudulent references for Low in his dealings with New York City developers.

Barnett told TRD that he signed the deal with the two funds in late 2007 or early 2008 — years before the 1MDB plot was ever even hatched. As for al-Husseiny, Barnett said he met him just twice.

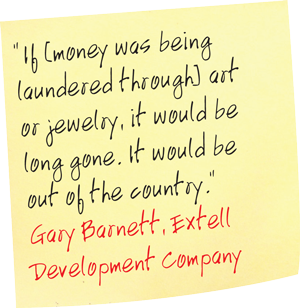

The developer said it may actually be a blessing in disguise that money is being stashed in real estate rather than in assets that can be physically moved.

“The good thing about having these people investing in real estate is that the Department of Justice now has something they can sell and probably get hundreds of millions of dollars out of,” Barnett said. “If that was art or jewelry, it would be long gone. It would be out of the country. This way, they can get the goods.”

“The good thing about having these people investing in real estate is that the Department of Justice now has something they can sell and probably get hundreds of millions of dollars out of,” Barnett said. “If that was art or jewelry, it would be long gone. It would be out of the country. This way, they can get the goods.”

And the government is seizing — or attempting to seize — some NYC properties.

In another recent money-laundering case, the DOJ tried to take control of a 36-story office building at 650 Fifth Avenue, home to tenants such as retail giant Juicy Couture. The feds first alleged in 2008 that the building’s owner — the Islamic cultural nonprofit Alavi Foundation — knew that its minority stakeholder, Assa Corp., was backed by state-controlled Bank Melli out of Iran. (Economic sanctions imposed by the U.S. prevent Iranian entities from buying real estate here.)

It was also alleged that Assa had improperly transferred rental income generated from the building to Bank Melli.

In July, a federal appeals court overruled a lower court, deciding that, for now, the building cannot be seized, but experts say the case exposes major blind spots in oversight of these transactions.

“It just shows how easy it is to use the anonymous ownership concept in real estate to get around even sanction laws,” said Heather Lowe, director of government affairs at Global Financial Integrity, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that focuses on illicit financing. “It’s amazing to think that Juicy Couture was paying rent to the Iranian government and nobody knew.”

But it’s not just money from America’s international adversaries that is cause for concern. It seems any developer who accepts capital from foreign investors is at risk.

Subrata Roy, the head of Sahara India Pariwar, the majority owner of the Plaza Hotel, is currently in jail over his own alleged real estate fraud scheme involving illegal fund-raising in the public markets in India. While the case did not involve money laundering, it’s yet another example of foreign investors parking dirty cash in New York commercial real estate.

The oversight problem

The fact that corrupt money is entering the U.S. is not lost on FinCEN.

650 Fifth Avenue, which the U.S. government tried to

seize in connection with a moneylaundering case.

In January, in a bid to combat money laundering, the Treasury Department launched a pilot program tracking all-cash purchases of luxury residential property made through shell companies in New York and Miami, an initiative that’s since been expanded to parts of California and Texas.

However, some industry insiders and lawyers who specialize in white-collar crime say the regulations missed the mark by failing to address money laundering in commercial property, which they argue is more vulnerable to abuse. That potential for abuse stems from the complex ownership structures in commercial deals.

“It’s deep cover. You can really hide behind it a lot easier than you can hide behind residential, where records are much more publicly available,” Apex’s Katz said.

FinCEN’s disproportionate focus on residential deals may even have unintentionally funneled more fraud into the commercial sector, said Andrew Bigart, an attorney at Venable.

“Anyone who’s interested in money laundering will find the path of least resistance,” he said. “As FinCEN has tightened the gaps with residential, it’s possible you might see some of that money flow into the commercial real estate sector.”

Attorney Ed Mermelstein, who often deals with clients from Russia and Eastern Europe, noted that on commercial deals, it’s not uncommon to have five, 10 or 15 limited partners in addition to general partners.

“Almost every party comes into the deal behind a legal entity,” he said. “If you start looking at the ownership tree, it winds up having so many branches that even attorneys get lost.”

Matthew Schwartz of Boies, Schiller & Flexner — a former prosecutor who represented Almaty and BTA in their case against the Chetrits — also noted that commercial real estate is often an ideal vehicle for money launderers.

“Residential properties, particularly if they’re investment properties, can have some of the same features, but, in general, they tend to be more straightforward,” he said.

A recent investigation by the New York Times into Chinese insurer Anbang Insurance Group highlighted just how complicated (and potentially dubious) the ownership web can get.

The newspaper found that Anbang, which recently bought the Waldorf Astoria Hotel for nearly $2 billion, is actually owned by a web of LLCs linked to a group of villagers in rural Pingyang County in China. Many of the villagers appear to be relatives of Anbang’s chairman Wu Xiaohui, who’s married to the granddaughter of legendary Communist Party leader Deng Xiaoping, prompting speculation that he was stashing stocks under the names of relatives, a process dubbed “white gloves.”

While Anbang has not been accused of any wrongdoing, it withdrew a bid to buy Iowa insurer Fidelity & Guaranty Life for $1.6 billion after U.S. regulators inquired into the details of its shareholders.

But ramping up oversight on the commercial sector may be easier said than done.

“I think FinCEN would very much like to expand its reach to the commercial real estate industry; I don’t think they think there’s less risk,” said Laura Marshall, a former Assistant U.S. Attorney who is now at law firm Hunton & Williams. “But the government works at its own pace.”

“I think FinCEN would very much like to expand its reach to the commercial real estate industry; I don’t think they think there’s less risk,” said Laura Marshall, a former Assistant U.S. Attorney who is now at law firm Hunton & Williams. “But the government works at its own pace.”

And even with evidence mounting that action is needed, that pace has been slow.

Exacerbating the problem is that many in the real estate industry are not trained to spot suspicious behavior, said Marshall.

Part of FinCEN’s decision to focus on illicit money in residential real estate — rather than commercial — may simply be a product of the fact that it was an easier fix, Boies’ Schwartz said. Until recently, all-cash residential transactions were completely bypassing “Know Your Customer” requirements — which were passed in 2002 and require all U.S. banks to collect information on a borrower’s identity and run security checks to ensure the customer’s name doesn’t appear on terrorist or criminal watch lists. The new LLC disclosure rules easily closed that gap.

In commercial real estate, problems are harder to identify — and most transactions already involve banks bound by KYC regulations.

Still, some said KYC requirements in the U.S. aren’t effective when it comes to flagging suspicious transactions — in part because enforcement is lax and not everyone adheres to the rules.

“It’s actually really embarrassing,” said Apex’s Katz. “They probably know who the principal sponsors are, but for minority investors, there really isn’t this emphasis on KYC. That’s why these things are happening in the United States.”

Still, FinCEN is beginning to take steps in the financial sector that could trickle down and create more scrutiny in commercial real estate — and actually identify minority investors.

In May 2018, FinCEN will begin requiring financial institutions to verify the true identities of beneficial owners — those with at least a 20 percent stake — of any legal entity opening a new account. They will also have to develop risk profiles and monitor those individuals on an ongoing basis.

As a result of these soon-to-be-implemented requirements, some developers are likely to start limiting the amount of money they’ll accept from individuals outside of traditional real estate circles. That, of course, will allow them to avoid increased scrutiny on their deals.

And some banks are already taking note.

“Some of our financial services clients are considering putting more scrutiny on large cash wire transactions involving real estate as a result of what is being perceived as heightened risk,” said Chris Faherty, a senior manager in the Investigation & Dispute Services practice at Ernst & Young.

Facing the fallout

The volatile capital markets may make it tempting for some developers to turn a blind eye to corruption and other potential pitfalls, sources said.

“When you’re someone who’s in desperate need of capital, it’s hard to ask tough questions,” said Venable attorney Ed Wilson. “I look at 1MDB and think some of these people involved probably had an idea.”

But the DOJ’s move in July to seize Low’s stake in the Park Lane could actually benefit the iconic property — if the government sells it and injects the project with new capital. After trading for $660 million in 2013, the hotel today could fetch $1 billion, sources told TRD. And that cash infusion could reignite lucrative condo plans, which Witkoff shelved earlier this year.

For Chetrit, who has not been the subject of any criminal investigation, the fallout from the partnership has nevertheless been more damaging.

In May, a New York State Supreme Court judge ordered a court-appointed monitor to oversee distribution of the funds the two Kazakhstani men invested in the Flatotel project — a move the Chetrits strongly fought, arguing that it would taint the project for potential buyers.

“The uniform perception of the marketplace, regardless of the exact details of the receivership, will be that the project is experiencing extreme financial distress,” Lee Eichen, a consultant for Chetrit, said in court papers. “This will lead to strong hesitation by prospective buyers (and the broker community at large), who will be reluctant to become involved in a project that they perceive may ultimately fail.”

As of May, there were still 22 unsold units at the 109-unit condo, representing an expected $148 million in revenue, or roughly 40 percent of the condo’s total projected sellout, court papers show. The Kazakhstanis will not be able to access the money they invested, pending an investigation.

Chetrit did not return TRD’s requests for comment, but a spokesperson previously told the Wall Street Journal that the claims had been “voluntarily dismissed with prejudice.”

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for Ablyazov’s family previously denied all accusations, saying they were politically motivated.

In general, it’s rare for developers to face prosecution in cases where they are caught in the crosshairs of shady investors.

And just because money has exotic origins, doesn’t mean it’s dirty. Barnett, for instance, reportedly made his initial capital in the diamond business, while the Chetrits trace their money back to textiles in Morocco.

But at the end of the day, KYC rules only apply to financial institutions, according to Schwartz of Boies, Schiller & Flexner.

“Other market participants don’t have that same legal responsibility but, in this day and age, everyone who is involved in business has some KYC responsibilities,” he said.

Industry experts said the U.S. is behind other countries in terms of KYC requirements. “The KYC rules in the U.S. are adhered to, to a much lesser extent than in almost any other country,” Katz said.

In addition, the U.S. doesn’t comply with financial reporting requirements set up by the international group known as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. That means that other countries report back to the U.S. government on bank accounts set up by U.S. citizens abroad, but the U.S. does not reciprocate, making it a favored offshore jurisdiction for international citizens looking to hide capital.

Many nonprofits and anticorruption activists are calling for greater accountability for developers, and even the brokers and attorneys who facilitate these deals.

“Many of the larger real estate companies will say, ‘Well, we don’t do any cash transactions, and the big banks are doing the due diligence, so we don’t have any obligation,’ ” said Shruti Shah, a vice president at anticorruption nonprofit Transparency International-USA. “But for any anti-money-laundering system to function well in any country, you need multiple checks and balances. It’s not enough that financial institutions are required to do due diligence. 1MDB shows that.”

Global Financial Integrity’s Lowe agreed, noting that law firms might be the best starting point.

“These people are handling huge amounts of money and there’s absolutely no reason why they shouldn’t have to do some due diligence checks,” she said.

“When someone comes to us for the purposes of defense, that is an area where you don’t report on what they’re telling you. That would be totally counter to the concept of justice,” she added. “But where an attorney is involved in transactional work, there’s no reason why they can’t look into who their clients are.”

Andy Singer, chairman and CEO of the Singer & Bassuk Organization, a Manhattan-based finance brokerage firm, said it’s in the developer’s best interest to vet their partners to avoid embarrassment or seeing the deal fall apart. “Self-preservation should be driving it,” he said.

Even so, the Hudson Companies’ David Kramer noted at the end of the day there’s still an element of luck.

“It’s hard to assess sometimes,” he said. “Today’s business hero, Enron, could be tomorrow’s criminal defendant. You can’t assume it’s all foolproof.”

Mermelstein said some New York developers simply refuse to take foreign money. In general, he added, the intensity of due diligence is “significantly higher” than it was just a year ago.

No developer “wants to have a knock on the door six months down the road, where an investigator is coming in looking for a former government official from Sudan,” he said.