Manhattan has a hotel room for every budget, whether it’s at a marquee address with $10,000-plus nightly rates or a no-frills establishment on a nondescript side street. But each of Manhattan’s hotel sectors is approaching today’s market, which is softening after a strong run, very differently.

Manhattan has a hotel room for every budget, whether it’s at a marquee address with $10,000-plus nightly rates or a no-frills establishment on a nondescript side street. But each of Manhattan’s hotel sectors is approaching today’s market, which is softening after a strong run, very differently.

At Manhattan’s toniest white-glove hotels — think the Waldorfs and the Pierres of the city — there are plenty of rooms going unbooked, but owners are keeping their rates sky-high. Meanwhile, according to industry players, the city’s limited-service hotels are slashing their rates in a frenzy to compete.

This month, The Real Deal examined three of New York City’s key hotel sectors: the luxury, limited-service and boutique markets. While hotel insiders track a slew of others, these three are each taking unique approaches to staying competitive in a changing market.

Since 2010, the number of Manhattan hotel rooms has shot up by an unprecedented 26 percent to just shy of 91,500 rooms, hospitality analytics firm STR reported.

That supply came along with a record 58.3 million visitors in the city last year, a number projected to grow to 59.7 million in 2016.

But industry insiders say that it’s not just supply and demand that determine the success of a hotel. Manipulating that supply and demand to maximize RevPAR — or the revenue pulled in from each available room — is just as crucial, they say.

Similar to the way airlines sell seats on flights, hoteliers change their room rates based on how full their hotels are. By pulling the rate and occupancy levers, operators can, to some extent, control how much money they bring in.

In addition, industry experts say despite the influx of new rooms, the market could be performing better if operators just managed their inventory better.

“Really, it isn’t a function of oversupply. It’s inventory,” said Richard Born of BD Hotels, one of New York’s largest independent hotel owners. “[It’s] a factor of how we market our rooms and our psychology.”

At the moment, the mental state of the market is at a crossroads.

Last year marked the first down year since 2009 for Manhattan’s hotel market, as RevPAR dropped 1.5 percent from 2014 to an average of about $288, according to data from STR. That was driven by declines in both occupancy and room rates in 2015.

Below is a look at how three of the hotel industry’s key sectors are handling the new market reality in the city that never sleeps.

Limited service

There are few “limits” to the number of hotels being churned out in New York’s so-called “limited service” sector.

These hotels — which include brands such as Marriott’s Courtyard and Hilton’s Hampton Inn, as well as smaller chains — have sprouted like dandelions on side streets in neighborhoods such as Chelsea and the Garment District.

Newcomers in the last year include the Lam Group’s 128-key Aloft in the Financial District, Palmetto Hospitality’s Hampton Inn just south of Times Square, at 220 West 41st Street, and Raber Enterprises’ 150-room Even Hotel on West 35th Street.

The segment, where room rates range from about $200 to $300 a night, has seen the largest increase in supply of any of the city’s hotel sectors in the past three years, while simultaneously operating at near-record occupancies.

But to pack their rooms in an increasingly competitive field, the operators of Manhattan’s limited-service hotels have been deeply discounting rates, industry watchers said.

“You do have a bit of a herd mentality,” said Lightstone Group president Mitchell Hochberg, who is developing four Marriott Moxy hotels in the city with some 1,500 rooms. “Some hit the panic button and get more worried about filling up beds, then a whole bunch of hotels cut rate.”

While a range of amenities — such as fitness centers, pools and meeting spaces — are offered in this category, the defining characteristic of limited-service hotels is that most don’t include a restaurant. Instead, they typically offer a continental breakfast or include a quick grab-and-go café in the lobby.

Hotels with rates in the middle 30 percent of Manhattan’s hospitality market had the highest occupancy rate last year at 88.7 percent, down from 89.5 percent the year before, according to STR. But the sector did see two other key metrics — average daily room rate and RevPAR — drop by 2.6 percent and 3.5 percent, respectively.

Industry insiders attributed the laser-like focus that limited-service hotels have on high occupancy rates to the rewards programs many offer.

Regular guests at Marriott- and Starwood-branded hotels, among others, can accumulate points for use toward free hotel stays and the corporate flags, then reimburse hotel operators for those free rooms.

But the hotels get higher reimbursements if their rooms are packed than if occupancy is low, said Michael Powlen of Hidrock Realty, which opened the Cambria Suites on 46th Street last year with its joint-venture partners North Carolina-based Concord Hospitality and the Maryland-based Choice Hotels. Hidrock is also co-developing a 317-room Courtyard by Marriott near the World Trade Center, at 133 Greenwich Street, and a 310-key Embassy Suites in Midtown.

“When the hotel takes that reservation, if that particular night it’s above 90 percent occupancy, the hotel will receive 80 percent of that day’s average daily rate,” Powlen told TRD. Conversely, he said, if the hotel is below 90 percent occupancy, the operator gets reimbursed at a much lower rate.

“It’s to the hotel’s advantage, especially if it’s a branded property, to run at high occupancy,” Powlen noted.

Born, whose company’s hotels include the Mercer Hotel in Soho, the Bowery Hotel in the Lower East Side and the Greenwich Hotel, said the competitive market has pitted skittish operators against each other in a race to the bottom: Once one hotel cuts rates, others follow suit to stay competitive, he noted.

“Who wants to do it? Nobody wants to do it,” Born said. “It’s like we’re all standing waist deep in gasoline and everybody lights the match.”

Luxury

The city’s most expensive hotels — which in some cases charge five figures a night — don’t seem all that concerned with packing the house.

These top-tier hotels are taking the exact opposite approach as their limited-service counterparts, focusing on rate growth at the expense of keeping the properties full.

Hotels with rates in the top 15 percent of Manhattan’s hotel market — including stalwart names like the Plaza, the Ritz-Carlton and the Four Seasons — bucked the market-wide trend and grew their rates, albeit by a modest 0.8 percent, to an average of nearly $480 a night, according to STR. (Although luxury hotels list rooms as high as five figures a night, the relatively small supply keeps the average much lower.)

Still, RevPAR in the luxury category fell, though only by less than 1 percent.

While the luxury segment didn’t see the same amount of new hotel supply as the limited-service sector, it did add rooms. Last year saw both the 114-room Baccarat Hotel and the 330-room Knickerbocker open.

As a whole, Manhattan’s luxury hotel market is more exposed to changes in supply than the limited-service sector, sources said.

“There are only so many luxury hotels in the city,” said Mark Van Stekelenburg, managing director of CBRE Hotels. “When another one comes in, it takes a little while for the market to absorb that and for the luxury properties to ramp up.”

But instead of dropping rates to absorb the new supply, Manhattan’s luxury hotels operated last year at about 80 percent occupancy, a drop of about 1.7 percent, according to STR.

Part of that willingness to operate at a lower occupancy has to do with the basic economics of running a luxury hotel, where staffing is so expensive.

“The luxury class typically presents the highest level of service with a higher staffing ratio,” Van Stekelenburg said.

The costs of employing such a high number of valets, concierges and housekeepers for every occupied room means it can actually be more cost-effective to operate fewer rooms, as long as the hotel can keep rates high enough.

But some say it’s also harder for luxury hotels to increase their rates once they cut them. As a result, they hold out on reducing rates longer — even if occupancy sinks.

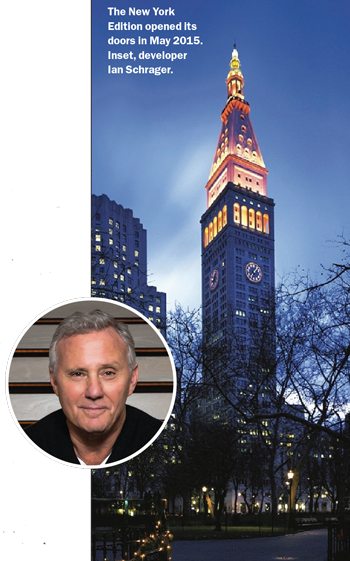

“The occupancy’s a little soft. The luxury guys are going to be a lot more reluctant to drop rate than the select-service guys,” said hotelier Ian Schrager, who converted the former Met Life Tower in the Flatiron District into the luxury lifestyle New York Edition hotel. Schrager is also collaborating with developer Steve Witkoff and investor Howard Lorber to bring an Edition to Times Square.

“When you reduce your rate during one 12-month cycle, it could take you two or three years to get back to where you were,” Schrager said. “There’s a reluctance in that high-end market.”

Boutiques

For Manhattan’s boutique hotels, the competitive advantage is all about how trendy and relevant they can remain in a city constantly looking to the next “it” spot.

Sources say smaller, independent hotels, such as the Ace Hotel in Midtown South, are operating somewhere between the extremes — not keeping occupancies as low as the luxury hotels and not dropping rates as much as the limited-service establishments.

“Our occupancy at the Ace has held in the mid-90s,” said Allen Gross, the president of GFI Capital Resources Group, which owns the Ace and developed the popular NoMad Hotel at 1170 Broadway. “We haven’t been able to grow rate that much.”

Gross is converting the landmarked 19th-century office building at 5 Beekman Street into a hip, 287-room hotel. The project, dubbed the Beekman, will include two restaurants run by Keith McNally, the restaurateur behind hot spots Pastis and Balthazar, and celebrity chef Tom Colicchio, one half of the partnership behind the Gramercy Tavern.

Bringing in a trendy destination restaurant, Gross said, is key to making a boutique hotel stand out. “You look around today, and the nicest restaurants are all located inside hotels,” he said.

Industry observers said the boutique space is not suffering from the same supply issue seen in the limited-service sector. And while the boutiques do face competition from Airbnb, the limited-service sector is more directly competing with the home-sharing website, said Henry Kallan, the president of the Library Hotel Collection, which owns and operates four boutique hotels in Manhattan, including the Hotel Giraffe on Park Avenue South and the Library Hotel near Grand Central Terminal.

Kallan said he’s been focused on keeping occupancy levels steady. A shift in occupancy by a few points can affect room rates by 5 to 10 percent, he said. That can significantly eat into a hotel’s profit margins.

Although tourists who stay in limited-service hotels may be more loyal to a brand than a specific property, Kallan argued that most boutique hotels enjoy the competitive advantage of steady repeat business.

“I think [boutiques] are more difficult to operate because the clientele is much more demanding,” he said. “But if you know how to operate the business, there’s a good chance you’ll get people coming back, and that pays dividends.”