Once upon a time, developers who were looking to make smart investment plays would throw up a building in Williamsburg, Long Island City or Bushwick and watch the buyers and renters flood in. But those neighborhoods have now largely topped out, sending investors on the hunt for the next corner of New York City that is ripe for opportunity.

This month, in an effort to suss out where real estate investors are making their next round of early bets, The Real Deal pored through building permits, demolition numbers and investment sales activity for more than 200 New York neighborhoods for the nearly 10-year stretch between 2008 and 2017. Then we zeroed in on outer borough areas with upticks in activity in the last year or two.

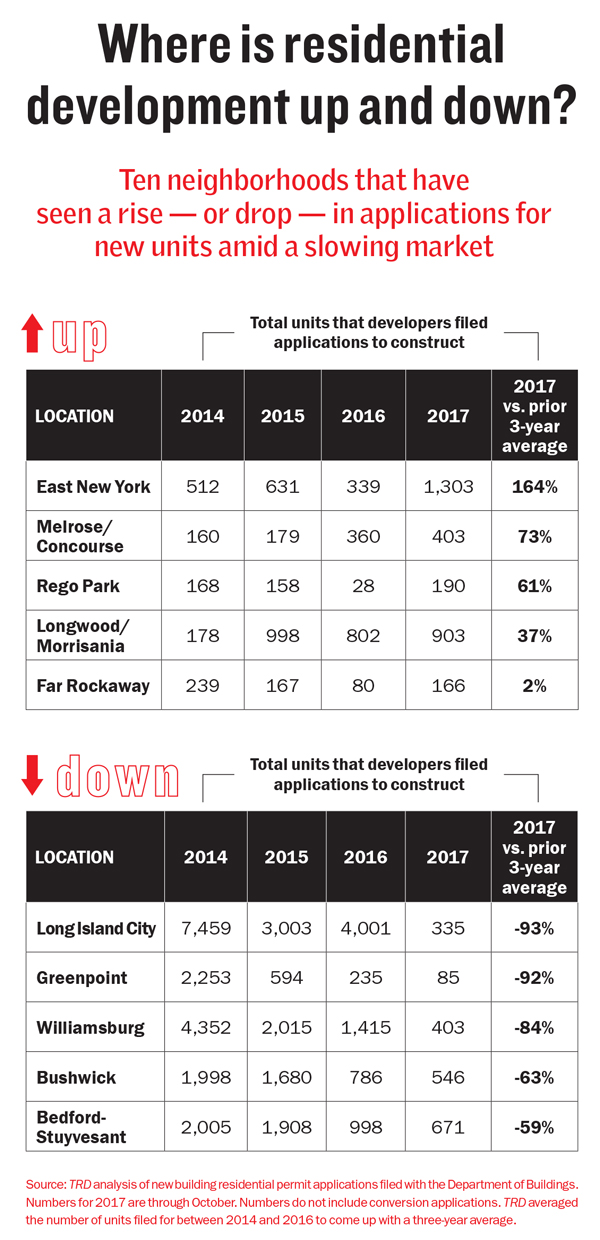

Unlike back in 2014, when developers were going gangbusters — pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into real estate — today’s investment dollars are largely down. Indeed, residential permit applications fell roughly 73 percent between 2014 and October 2017, plummeting to roughly 18,000 from nearly 66,000.

And while the household-name neighborhoods of the last peak are still seeing activity, it’s a fraction of what it was a few years ago.

Long Island City, for example, saw a 95 percent drop in residential units applied for from 2014 (when there were 7,459) to 2017 (when there were only 335 through October). Williamsburg saw a 90 percent drop in the same category during that same time window — developers in the neighborhood filed for 403 units in 2017 versus 4,352 in 2014. And Bushwick logged a 73 percent decline, falling to 546 in 2017 from 1,998 units in 2014.

“There’s just so much going on there,” said Aaron Jungreis, president of Rosewood Realty Group, referring to neighborhoods like Williamsburg and Long Island City. “There’s so much product that’s saturated [the market].”

In many ways, today’s real estate investments plays are not as clear-cut as they were when the market was firing on all cylinders. For starters, investment dollars are spread out among more neighborhoods and are harder to track because the numbers are not as large.

But with all that in mind, TRD identified a handful of under-the-radar neighborhoods (some with very little name recognition, others with more), that are bucking the trend and seeing an uptick in activity. Those neighborhoods — East New York in Brooklyn, Melrose/Concourse and Longwood/Morrisania in the Bronx and Rego Park and Far Rockaway in Queens — are all at different stages of investment maturity. Some are seeing an influx of affordable housing development. Others are squarely in the market-rate game.

Jungreis said investors in East New York would likely have to start off by buying land rather than buildings.

Jungreis said investors in East New York would likely have to start off by buying land rather than buildings.

“It’s hard to build scale there,” he said, noting that it’s still difficult to obtain large property portfolios in the neighborhood. “Anyone who’s going to get scale in that neighborhood is going to have to do it via [buying] land and then building on top of the land.”

One big factor fueling investment in that neighborhood is falling crime. In the police precinct covering East New York, for instance, murders plummeted nearly 67 percent and shootings fell about 60 percent over the last seven years.

The South Bronx has also seen sharp decreases in crime, and Jungreis argued that it’s further along on the investment front, with several new developments already in the works.

“It has a lot going for it. I think it’s a high climb also, but it’s not as high as East New York,” he said.

Tom Donovan, a vice chairman at Cushman & Wakefield’s capital markets group who focuses on Queens, said the latest trend for developers in Rego Park is buying adjacent single-family homes, demolishing them and replacing them with 30- to 40-unit apartment buildings.

“They’re knocking them down and building these sexy boutique apartment buildings,” said Donovan, noting that developers in the area are seeing sizable returns.

To be sure, TRD’s neighborhoods are not the only areas that have seen an uptick — others, like Sheepshead Bay and Red Hook, have also seen their numbers rise.

But sources said these five areas are worth watching.

In some cases, they are now matching (or topping) the stats being seen in their much higher-profile counterparts. For example, both Williamsburg and Melrose/Concourse had 403 residential permit applications filed in 2017. Meanwhile, Longwood/Morrisania had 903, compared to Long Island City’s 335, and Far Rockaway had 166 versus a measly 85 in Greenpoint, according to TRD’s analysis of data from the Department of Buildings.

The numbers are not as clear for investments sales for both development sites and cash-flowing properties, according to a TRD analysis of sales recorded with the Department of Finance. But TRD’s five neighborhoods have all trended up on average for the last several years, even if their dollar volumes were lower than some of the hipper outer borough areas that have recently topped out.

Long Island City, for example, saw commercial sales volume come to a screeching halt in 2017. It logged nearly $280 million in deals last year through October, but that was down from $1.7 billion just one year earlier. Williamsburg saw a similar trend, netting $311 million in deals in 2017 versus a peak of nearly $733 million just two years earlier.

Melrose, however, is on the upswing. It saw $210 million in deals in 2017, a 31 percent increase from $160 million the year before. Rego Park saw $143 million in deals, which was down from the year before but up dramatically from $7 million in 2014.

In many cases, these neighborhoods are also benefiting from rezonings.

Far Rockaway is one of those areas. Cushman’s Donovan said the neighborhood, where he pegged cap rates — or the rates of return based on the expected income — at 5 percent to 6.5 percent, has also benefited from improved transportation.

“It used to be an isolated peninsula where you went to the beach, and you had to go home over the bridge to do any kind of shopping,” said Donovan. “Now, people go and spend the whole day there.”

In general, these neighborhoods are obviously not attracting the same kinds of dollars that, say, Midtown Manhattan is. But they do offer investment upshot in terms of yields. “There’s more risk, but that’s why there’s a higher reward,” Donovan said. “You’d be hard-pressed to find anything close to a 5 percent [cap rate] in Manhattan.” —E.S.

Rego Park, where developers have added both new condos and rentals.

Rego Park, Queens

Both residential construction and investment sales are skyrocketing, but the area is better for long-term plays

Hipsters and Rego Park might not get along very well.

“It’s not trendy enough for them,” said Kobi Zamir, a broker with GFI who focuses on the neighborhood. “They’re looking for more nightlife, and I think it’s a little bit lacking in Rego Park.”

Luckily for the Queens neighborhood — a roughly two-square mile area, which is nestled deep in the borough between Forest Hills and Elmhurst and located right along the Long Island Expressway — there are plenty of less-hip New Yorkers and real estate players who like what it’s selling.

The number of applications for residential units in Rego Park jumped 116 percent to 190 in 2017 from 88 units back in 2008, according to TRD’s analysis.

While those numbers are undoubtedly tiny compared to anything a Manhattan neighborhood would log, commercial sales volume skyrocketed as well, jumping to $143 million in 2017 from about $112 million in 2008 after peaking at about $203 million in 2016.

Developers have added both new condos and rentals to the neighborhood, where median rents clock in at roughly $2,275 and median sales prices are a modest $392,000, according to StreetEasy.

Aaron Hillel, a broker with the Hillel Group, said interest in the neighborhood has spiked as more buyers and renters realize that the commute to Midtown is about 30 to 40 minutes and that the area has an array of retail, including several large brand-name stores.

And bigger investors are clearly circling in pursuit of the returns.

In July 2016, for instance, Madison Realty Capital and Ariel Capital dropped $136 million on the 419-unit Saxon Hall rental complex at 62-60 99th Street — the largest transaction in Rego Park history.

Blumenfeld Development Group also placed a big bet on Rego Park last summer, scooping up 99-01 Queens Boulevard from Vornado Realty Trust for $31.2 million. (Vornado is a major investor in the area. It owns the Rego Center, a large shopping mall that opened in 2010 and anchors the neighborhood, along with the Alexander, a 312-unit luxury rental above the mall.)

Meanwhile, Queens residential developer Kenny Liu is planning a 50-unit condo that will include a 12,000-square-foot health care facility on the first two floors.

The investment sales market in the area was also stirring near the end of 2017. In October, a Manhattan-based real estate firm bought a 113-unit residential building for $31.5 million, and the LeFrak Organization sold an 11-story office building.

Modern Spaces CEO Eric Benaim described Rego Park as a better play for a long-term investor than for someone looking for a quick turnaround.

“If somebody’s looking to buy, fix up and flip right away, I don’t really see that being that lucrative,” he said. “It’s more for somebody looking to buy something, fix it up or do ground-up construction and hold it for five or 10 years.” —E.S.

Concourse/Melrose, The Bronx

A famed fountain in the Grand Concourse’s Joyce Kilmer Par

Affordable developers are rushing into the South Bronx nabes with large-scale projects underway — and market-rate players are no doubt next

For most New Yorkers, Melrose and Concourse are key points of reference in the Bronx — whether they know them by name or not. That’s largely because they are home to well-known destinations like Yankee Stadium and the borough’s courthouses.

But lately, in a major about-face, the adjacent South Bronx neighborhoods have seen a flurry of new investment activity.

In 2008 and 2009, the neighborhoods had zero new residential units in the pipeline. But in 2016, developers filed permits for 360 new units, and in 2017 they topped that and added another 403.

Commercial sales activity has also shot up, jumping to $210 million in 2017 from about $85 million in 2008 after peaking at $228 million in 2014.

And if Starbucks is still a true sign of gentrification, then Concourse landed on the real estate map in 2015 when the coffee chain opened its first local outpost, on East 161st Street. (Chipotle debuted next door two years later). Melrose, meanwhile, recently saw the opening of Italian restaurant Porto Salvo, which is serving octopus carpaccio and mango-and-arugula salad.

On the development front, two of the borough’s most anticipated projects — La Central in Melrose and Bronx Post Place in Concourse — are currently under construction.

La Central is located right by the Hub, a major retail center. It will contain almost 1,000 affordable rental units, along with a roughly 50,000-square-foot YMCA and a host of other amenities, including a rooftop telescope. Hudson Companies began work on phrase one of the project, which has a $335 million price tag, over the summer.

Just one subway stop away, Youngwoo & Associates is transforming the Bronx General Post Office into a mixed-use complex with ground-floor retail, office space and dining.

And Azimuth Development Group and the Upper Manhattan Development Corporation have filed plans to bring three affordable rentals with a combined 275 units over about 213,000 square feet to the area.

Hudson Companies’ Aaron Koffman said that he does not think the Melrose area is quite ready for a market-rate development on the scale of La Central. While he’s seen investors start coming in, they’ve mainly been land speculators.

“I see a lot of flippers. They buy and they don’t even fix it up,” he said. “They buy it, hold it for six months and then try to sell it for a 40 percent return.”

One thing that investors are undoubtedly eyeing is crime, which has dropped substantially in both neighborhoods in the last seven years.

And Mable Ivory, a real estate agent at Engel & Völkers who focuses on the South Bronx, said interest in Concourse has been growing as high-profile projects get closer to reality.

“A lot of people are coming from the city — all parts of the city,” she said. “It used to just be Harlem and Upper Manhattan. Now I have people coming to Concourse from Brooklyn, from Queens, from New Jersey even. They’re finding they get a lot for their money there.”

Market rate developers are no doubt next in line. —E.S.

Longwood/Morrisania, The Bronx

The adjacent neighborhoods have seen residential applications skyrocket over the past decade

Longwood and Morrisania may not have completely escaped the problems that plagued the South Bronx during the infamous 1970s, but there are growing signs that the two adjacent neighborhoods are ready for their time in the spotlight.

A brownstone-lined street in Longwood’s historic district

The number of proposed residential units in Longwood and Morrisania skyrocketed 1,137 percent from 73 in 2008 to 903 units last year, according to TRD’s analysis of DOB data. Commercial sales volume has more than doubled, jumping to $152 million from about $64 million over the same time period.

Haniff Baksh, principal broker at the Bronx’s Besmatch Realty, said there has been a particularly strong uptick in renovations to the neighborhoods’ older housing stock.

“What we’re seeing is a lot of these older properties, they are being sold,” he said, “[and] either rehabbed, or in some cases there are some new developments in the area.”

The current housing stock in Longwood and Morrisania is a mixture of properties ranging from smaller one-family homes to public housing to apartment buildings with roughly 40 to 50 units, Baksh said. But some developers have filed plans for much larger projects in the neighborhoods.

The Ader Group, a real estate investment firm based upstate, is planning a 14-story, 243-unit affordable building on the site of a former parking facility — the first phase of a two-building, 474-unit complex. Additionally, Manhattan-based Property Resources Corporation filed plans for an eight-story, mixed-income building alongside two five-story buildings at 970 Kelly Street, a development that will contain 161 residential units. And on the border of Morrisania and Melrose, BFC Partners and WHEDco are planning the massive Bronx Commons project, which will include 305 affordable housing units and a 300-seat music hall.

Land prices in the area are generally between $50 and $60 per buildable square foot, according to Michael Tortorici, executive vice president at Ariel Property Advisors. He said that returns are currently easier to come by with affordable developments, but market-rate projects will likely become more prevalent.

“The difference between market-rate and affordable in the Bronx is not as wide as in other areas of the city,” he said. “So when subsidies are available to do affordable, sometimes it tips the scale to do it that way.”

Liang Li, a real estate agent with Nest Seekers International who lives and works in Longwood, said he’s lately been seeing more interest in the neighborhood from Harlem residents who are looking to get more space for less money.

“Not just the rent part,” he said. “It’s also cost of living. Just by comparing the cost of coffee or orange juice, I think that also matters for some people.”

Median asking rents in Longwood were $1,825 and $1,900 in Morrisania as of November, according to StreetEasy. That was significantly cheaper than East, Central and West Harlem, where they were $2,300, $2,397 and $2,725, respectively.

Median asking rents in Longwood were $1,825 and $1,900 in Morrisania as of November, according to StreetEasy. That was significantly cheaper than East, Central and West Harlem, where they were $2,300, $2,397 and $2,725, respectively.

However, Longwood and Morrisania still lack some of the hallmarks of gentrifying areas. For instance, there has yet to be a burst of trendy new restaurants and cafes. Retail in the neighborhood, concentrated on Boston Road and Third Avenue, is largely a mix of discount stores, hair salons, delis and other small businesses.

Morrisania is part of the poorest neighborhood district in NYC, according to city statistics from 2015, while in Longwood, almost 50 percent of households are considered “rent-burdened.” However, crime has been steadily dropping. Over the past seven years, murders in the precincts covering Longwood and Morrisania have dropped 50 percent and 20 percent, respectively, according to stats from the NYPD.

Tortorici said investors based in Manhattan are eager to snatch up multifamily properties throughout the Bronx, and Longwood and Morrisania are no exception to this.

“I think Manhattan investors are looking at any multifamily that they can see in the Bronx. I don’t think it’s exclusive to necessarily a neighborhood,” he said. “If it’s in Longwood or Morrisania, they’re paying attention to those offerings.” —E.S.

East New York, Brooklyn

Affordable housing is where profits are currently penciling out, but questions are swirling about when the area will be ready for market-rate

When Brooklyn’s East New York was rezoned in 2016, it touched off a real estate makeover.

That year, developers filed applications for 339 residential units. But in 2017 that number shot up by 284 percent to 1,303 units — many of them heavy on the affordable housing.

A handful of developers have gotten in on the ground floor.

Multifamily developer Radson Development is preparing projects for two vacant lots: one a 235-unit mixed-use, 12-story building on Linden Boulevard, the other a 521-unit affordable housing-and-retail complex on Loring Avenue.

Meanwhile, Monadnock Development, the East Brooklyn Congregations and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development filed plans in September for a 240-unit affordable rental development as part of the sprawling Nehemiah Spring Creek development, which sits on city-owned land adjacent to the Gateway Center shopping mall.

And Phipps Housing is diving in with a 403-unit affordable housing complex on Atlantic Avenue in Cypress Hills, a section of East New York.

Though some of those developments are outside of East New York’s rezoned area — which includes about 190 blocks, roughly between Fulton and Belmont avenues — competition for investment properties in the area is strong.

That may be because residential prices in East New York have shot up 45 percent since 2012 — the same sort of jump being logged in pricey Brooklyn neighborhoods like Carroll Gardens and Park Slope, according to PropertyShark.

“There’s a lot of cash buyers coming in looking for good deals, mostly for [two- and three-family homes they can rent out] anywhere under the million-dollar range,” noted Citi Habitats broker Kendall Vidal, who said he has 20 interested parties for one property he’s selling in the neighborhood.

Investors are “super interested in the area,” partly because they are banking on the fact that buyers and renters will increasingly get priced out of other areas and turn to East New York as a cheaper alternative.

The neighborhood — which is on six subway lines and the Long Island Rail Road — is a short train ride from Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant, where rents shot up by 44 percent and 36 percent, respectively, between 1990 and 2014. But it has a different genetic makeup.

“A lot more rental units in East New York are rent-stabilized and rent-controlled than in Bushwick and Bed-Stuy,” said Ideal Properties Group’s Aleksandra Scepanovic.

Real estate players say that for now, affordable housing is where profits are penciling out. That’s thanks largely to the availability of tax-exempt bonds and government subsidies.

“I don’t see a huge rush of for-profit buying at these prices to build market-rate housing,” said Alan Bell, a principal at B&B Urban, which is building a 100-unit affordable rental project in the area.

Bell, whose firm invested before the rezoning was finalized and land prices shot up, said he’s not sure whether B&B could make the project work financially now. In some cases, property owners are looking for prices between $70 and $80 per buildable square foot, he said. That’s almost twice the roughly $43 average the neighborhood was seeing in 2014, according to TerraCRG.

“Owners of property are going to have to get more realistic, [and] when it happens I’ll be ready to jump,” Bell said.

In general, East New York is not without its warts. While crime has fallen 73 percent since 1990, more major crimes were committed in East New York and Cypress Hills than in any other precinct citywide in 2017. And crime there was twice what Williamsburg and Bed-Stuy saw, according to the NYPD.

And commercial sales volume has not seen the same bump as residential. While there was $155.5 million in commercial deals in 2017 — a 27 percent increase from 2008 — the neighborhood peaked in 2015, when $274.8 million in property traded hands.

Bell said the first wave of market-rate housing will likely get built on smaller plots, where sellers may be more willing to drop prices. Those who own large parcels, he said, are more likely to wait for the big money to arrive down the road. —D.L.

A stretch of beach on the peninsula, where major developers are building rentals and condos

Far Rockaway, Queens

With a fresh rezoning and new transit improvements, major NYC developers have upped their interest in the seaside enclave

Far Rockaway may be one of the farthest-flung parts of the city, but over the past few years that hasn’t been much of a detriment to development. And a rezoning and new ferry service to Lower Manhattan are only adding to the boom.

Several big-name developers have taken note of the area’s investment potential in the last few years, rushing to erect a mix of affordable and market-rate projects in the Queens neighborhood.

For instance, Related Companies is planning a 145-unit below-market-rate project in downtown Far Rockaway north of its Gateway Apartments complex, and the Marcal Group is building a condo along Beach 116th Street, where units will likely go for between $500 and $600 per square foot.

MDG Design + Construction, meanwhile, is also making a big play on the peninsula. The firm recently landed a 99-year lease for the NYC Housing Authority’s Ocean Bay apartments, which it’s pouring $560 million into renovating. And Michael Stern’s JDS Development is completing a 60-unit rental with prices ranging from $2,650 to $4,300 — significantly higher than the Rockaways’ median asking rent, which stood at $1,895 as of November, according to StreetEasy.

Marcal CEO Mark Caller said investors in Far Rockaway are looking to either buy land for future projects or snap up existing buildings. But he noted that it’s a tricky area to invest in, because it’s not as established as other NYC neighborhoods and because building requirements have become increasingly stringent since the area was devastated by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Marcal’s project, for example, will not have any residential units on the first floor, and the JDS project is designed with flood vents.

But Caller said the boom in the Rockaways is very real. “We’ve watched the trends of home prices moving up and more and more people coming into the Rockaways,” he said. “We’ve seen a real resurgence.”

The neighborhood is indeed much further along than all the others on TRD’s list — with major Manhattan players like Related and JDS already placing their bets. But the numbers are not as striking — the area saw a 2 percent increase in residential applications in 2017 compared to the prior three-year average. That might be because developers caught on to the area long before they moved into some of those other neighborhoods. But Far Rockaway was rezoned in September, sparking a new round of investment interest.

Developers filed applications for 166 new residential units in Far Rockaway in 2017, more than twice the previous year and roughly the same as what they filed when the market was booming in 2015. The number of proposed new units peaked at 239 in 2014.

Commercial sales volume in the neighborhood only totaled about $19.7 million in 2017, but it has been much higher in recent years, hitting a recent peak of about $109 million in 2014. Caller estimated that land typically goes for about $60 per buildable square foot in Far Rockaway, offering developers a cheap alternative to pricier areas of the city.

Median home prices were hovering between $400,000 and $500,000 throughout much of 2017, and sales volume has been increasing over the past few years, according to StreetEasy. The area had nearly 530 residential sales in 2017 as of November — up from below 400 from 2011 to 2014 and down slightly from a peak of almost 600 in 2015.

Even the area’s infamous inaccessibility has become less of an issue, thanks to ferry service that launched last May between Far Rockaway, Sunset Park and Wall Street.

Although the beach remains the biggest draw — and trendy bars like the Rockaway Beach Surf Club with its Mexican food outpost, Tacoway Beach, bring Manhattan and Brooklyn crowds during the summer — the area is becoming more popular in the off-season, said Lisa Jackson, broker/owner of Rockaway Properties.

“People are opening up businesses and realizing that this is a year-round place,” she said. “Airbnb is now popular here. They’re building hotels. They have more apartments, so there’s a lot more going on.” —E.S.