Before climbing into bed on June 11, Robert Nelson found himself bracing for a “horror show.”

The leaders of the state Senate and Assembly had just announced that they’d reached an agreement to radically tilt rent regulations in favor of tenants, curbing how landlords in the city could increase rents on roughly 1 million stabilized apartments.

“My heart dropped. I was in disbelief,” Nelson said. “That was a really poor night’s sleep. I don’t think anyone in this business in their wildest dreams could have ever expected them to act so irresponsibly. I think it’s a travesty.”

In the final days leading up to the bill’s passage, others were scrambling to kill it before it reached Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s desk. Some of the city’s largest developers frantically called the governor, pleading with him to swoop in and kill the legislation at the last moment. He said no. Real estate lobbyists who remained in Albany admitted that the dramatic changes were all but inevitable, even as they continued to field calls from upset clients and tried to secure last minute meetings with state officials.

“Could it have been worse? Yes,” one real estate lobbyist said on condition of anonymity. “Rents could’ve been socialized.”

Related: Brutal brokerage realities

Though many of the consequences predicted by the real estate industry — like the decline of the city’s housing stock — would take several years to materialize if they were to come to fruition, fallout from the new law was swift in other ways.

Two landlord groups — the Rent Stabilization Association and the Community Housing Improvement Program — threatened legal action against the state in July challenging the new law’s constitutionality. And less than two weeks after the law was signed, Real Estate Board of New York President John Banks announced that he would leave his post to be replaced by Executive Vice President Jim Whelan, who has a reputation as a quiet but dogged industry operative, on July 1.

Banks said the rent law had no bearing on his decision to step down. But his departure comes as REBNY is facing immense pressure from its members to reinvent how it navigates a legislature that is drifting further left. Meanwhile, multifamily owners — some of whom based their entire business models on being able to flip regulated units to market rate — say they are grappling with difficult decisions, like whether to hold onto their portfolios or find other ways to cut costs.

Banks said the rent law had no bearing on his decision to step down. But his departure comes as REBNY is facing immense pressure from its members to reinvent how it navigates a legislature that is drifting further left. Meanwhile, multifamily owners — some of whom based their entire business models on being able to flip regulated units to market rate — say they are grappling with difficult decisions, like whether to hold onto their portfolios or find other ways to cut costs.

Many landlords say the changes will result in a mass flight from the New York City market and the deterioration of the city’s housing stock as owners cut back or halt renovations altogether. Some have speculated that well-capitalized real estate investment trusts, private equity firms and pension funds could view the changes as an opportunity to buy up distressed properties.

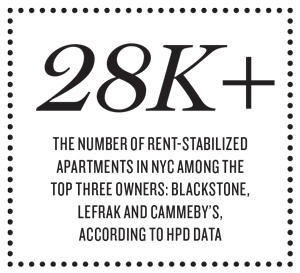

Blackstone Group, LeFrak and Cammeby’s International have the most rent-stabilized holdings in the city, with more than 28,000 rent-stabilized units between the three firms, but they may not necessarily be the landlords hit hardest by the new law. Big and small, companies that rely heavily on unlocking value by converting rent-stabilized apartments to market rate will find it much harder to do so. And while there’s no available data as of yet on the law’s impact on rental property values, some in the real estate business are projecting they could drop by 10 percent or more in the near future.

Laura Wolf-Powers, a professor of urban planning at CUNY Hunter, said those who will lose the most are the owners who are overleveraged or beholden to equity investors demanding big returns.

“The most impacted parties will be owners who treat residential buildings as commodity assets for which other investors compensate them, rather than as housing for which residents compensate them,” she noted.

But industry sources say smaller landlords will be most impacted by the changes, especially those who depended on Major Capital Improvement and Individual Apartment Improvement programs. These programs, which have been severely curtailed, allowed landlords to raise rents on regulated apartments permanently after doing renovations on their buildings.

“The ones who are going to be impacted are the small guys outside Manhattan,” said RSA President Joseph Strasburg. “Tenant advocates can take their victory lap, but clearly there’s a price when things do hit the wall.”

Coping with change

New York real estate players across the board were in shock on the night of June 11, when the final Senate and Assembly proposal was released.

Robert Nelson of Nelson

Management

The reforms went far beyond what the industry had been preparing for, even though changes to the MCI and IAI programs were widely expected. Cuomo had already made it clear that the vacancy bonus, which allowed for rent increases of up to 20 percent once apartments became vacant, was on the chopping block.

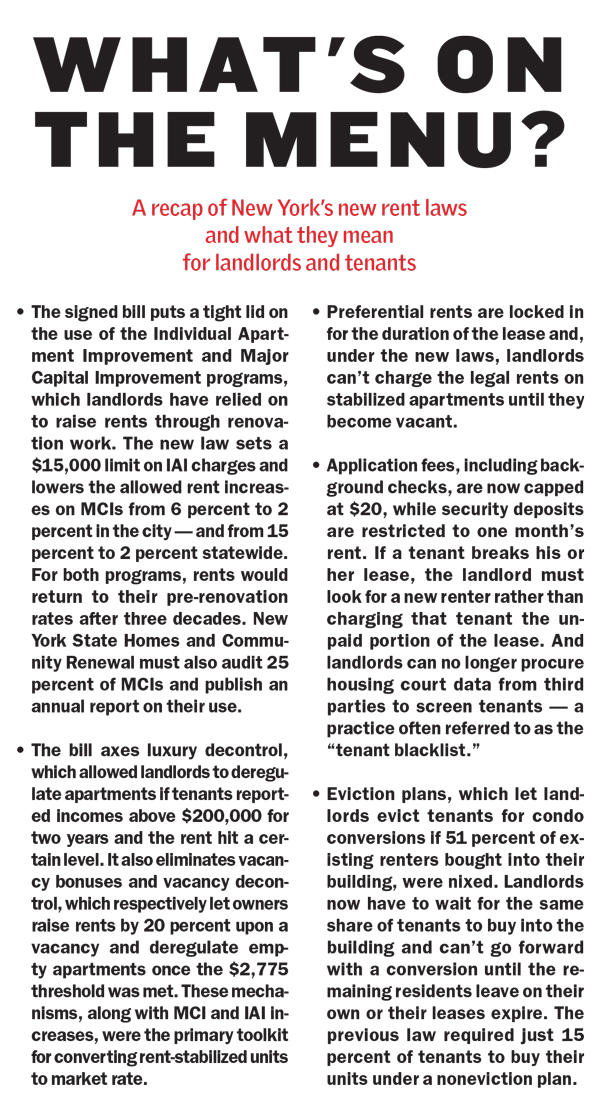

But the final bill included drastic changes to those financial incentives, capping the total renovation costs that can be passed on to tenants at 2 percent and $15,000, for MCIs and IAIs respectively. The measure also limits the duration of these rent increases to 30 years, meaning that rents would eventually return to their pre-renovation rates. The new legislation also froze preferential rents — rates below the legally permitted rent — for the duration of existing leases and upon renewal, so landlords can no longer abruptly hike rents.

And the elimination of vacancy decontrol, under which landlords could flip apartments to market rate if a rent threshold was met and there was a vacancy, radically changes the playbook for raising income. Many loans had been issued under the presumption of being able to deregulate rent-stabilized units.

That has been the go-to strategy to increase rent rolls in the city’s multifamily market since 1994, when vacancy decontrol was enacted. The tool set a target rent rate for deregulation, which was most recently set at $2,775, with multiple paths to hiking rent through renovations, vacancies and tenants who reported higher incomes.

At least 291,000 apartments have been deregulated in the past 25 years, according to the Rent Guidelines Board, and a 2017 report by Urbanomics commissioned by RSA found that the industry spent $8 billion on construction work to deregulate apartments in that time frame.

The latest changes in Albany left some landlords feeling like the carpet had been pulled out from under them. Nelson, whose eponymous firm owns 3,000 rent-stabilized apartments throughout New York City, called the changes “blasphemous” and said that the new law has turned real estate into a social service industry. He also lambasted the New York City Democratic Socialists for ramming the legislation through, despite the real estate industry’s lobbying efforts.

“It’s almost like you’ve sent me out into the world and said, ‘go to the store and buy all these things,’ but you’ve cut off my arms,” Nelson said. “How am I going to push the cart?”

Now landlords who were expecting to do business under one set of rules are left to pick up the pieces.

Those who purchased their properties with the explicit intention to flip them to market rate will be most impacted by the new law, said Edward Kalikow of the Kalikow Group, which owns and manages about 6,000 rental units in the five boroughs and Nassau County. Even though 90 percent of Kalikow’s portfolio is rent-stabilized, the company isn’t looking to sell off assets. Instead, it is cutting back on renovations and giving up on making any new acquisitions in the city.

“Anyone that bought a property at a 3 or 4 percent cap rate, planned to turn over units legally, that business model is going to be completely destroyed,” he said.

A renovation drought?

Since the bill was signed into law, there has been a flurry of speculation that the new caps on MCIs and IAIs would halt renovation work, eliminate contractor jobs and result in the decay of the city’s aging housing stock.

John Tashjian, a founder and principal of Centurion Real Estate Partners, which focuses on rental-to-condominium conversions in New York and Los Angeles, said the industry knew there was a balance that needed to be struck on reimbursements for renovation costs. But he argued the changes were “pushed past reason.”

“Stripping them of the programs means no landlord will ever put another dollar into a rent-stabilized apartment,” Tashjian said.

Though the caps to both programs are far-reaching, experts say that owners are not likely to stop investing in their properties completely. Wolf-Powers said rental housing market conditions will largely depend on construction costs and maintenance expenses, and that the city is unlikely to let landlords go under because they can’t afford major improvements.

“If owners run into trouble with an unexpected need — say, to replace a roof or a boiler — HPD has an extensive menu of low-interest loan products,” she said. “The city is not going to let a responsible landlord go out of business because they can’t finance a capital improvement.”

But a handful of other owners and operators say the quality of their renovations will take a hit.

Marla Siegel, executive director of property management at Sugar Hill Real Estate, which owns approximately 1,300 rent-stabilized units, mostly in Upper Manhattan and Brooklyn, said one of her firm’s biggest concerns is the impact on basic necessities such as painting common areas, upgrading lighting and installing security systems.

“This is a total about-face in the way we operate,” she said. “Jobs will be impacted, and so will our ability to make improvements in buildings that are really old. Oftentimes when we acquire them, they’ve been undermanaged and not maintained for many years.”

Other real estate players say that while the changes to the programs are significant, the effect may just be to alter the kind of finishes they’re able to do on rent-stabilized apartments.

Charles Bendit, whose company Taconic Investment Partners owns about 2,000 rent-stabilized units in the city, mostly in the Bronx, said the firm will be recalibrating the improvements to its apartments.

“We may not be upgrading apartments to the same standard,” Bendit said. “We’ll be cutting back significantly on improvements to individual apartments’ living experience. They may be more affordable, but not as nice to live in.”

Adam Mermelstein of Treetop Development, which owns roughly 1,300 rent-stabilized units in New York City, echoed that sentiment.

“I can tell you, without a doubt, we’re not going to be performing the type of high-end, high-level renovations when an apartment becomes vacant,” he said. “We are of course going to be ensuring it complies with code and is quality housing, but we won’t be doing the high-level luxury renovations that we were performing up until now.”

Advocates have long argued that rent-stabilized apartments were never meant for luxury finishes in the first place, and that the practice led to speculation.

“Rent-regulated tenants want apartments that are safe, decent and habitable. They don’t need granite countertops and stainless steel appliances,” said Ellen Davidson of the Legal Aid Society, a nonprofit organization. “What they need are refrigerators that work.”

And over the past several years, tenants and public officials have accused some landlords of abusing the IAI and MCI programs by inflating renovation bills and, in some cases, not actually performing the work required to raise rents.

Marla Siegel of Sugar Hill Real Estate

Scott Short, of the nonprofit development organization RiseBoro Community Partnership, said he supports the changes to MCIs and IAIs. Prior to the new law’s passage, the programs invited a wave of speculative buying that led some developers to expect an unreasonable windfall from stabilized properties, he added.

“That was really a perversion of the system,” Short said. “It was established to allow owners to maintain their buildings and maintain a reasonable profit.”

Escape from New York

Faced with the stringent rent regulations, some longtime multifamily owners may soon hightail it out of the city to new markets.

Irving Langer’s E&M, which still owns roughly 3,000 rent-stabilized units in the city, was one of the first companies to start selling off some of its New York City portfolio and move upstate to evade rent regulations. The company sold off dozens of its East Harlem properties last year and recently acquired a handful of large rental properties in the Hudson Valley.

Centurion’s Tashjian said his firm will be looking to move to Florida, business-friendly coastal cities and high-growth inland cities. Sugar Hill’s Siegel said her company is also weighing its options and considering areas outside of the five boroughs, including upstate.

“We are reevaluating the buildings we currently own and operate, and taking a look at our investments and where else it makes sense to invest,” she noted.

Chris Athineos, who owns nine buildings with 150 apartments in Brooklyn, said he’s considering selling two of his properties and plans to stop all renovations for the time being. Depending on how the market looks after he sells those two, he may consider shedding his entire portfolio.

“I’m not saying I’m going to sell everything tomorrow,” Athineos said. “Maybe our long-term plans in five or 10 years, we would go that route.”

Jennifer Recine, a partner at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan, said some investors have asked her law firm to scope out markets outside the state to gauge whether their governments will implement similar rent regulations to New York’s.

Of course, there’s a learning curve for many seeking entry into markets outside the city or state — it would require building relationships with new lenders and local officials. And Recine said she doesn’t think the changes will herald mass flight from the city.

“It’s too cynical to say there will be a wholesale exit from the state by developers looking for better regulatory climates,” she said. “Developers with active New York portfolios will refocus on having a productive dialogue with lawmakers and tenant groups. Certain parts of the new laws are incompatible with owners’ business models and prior laws passed to incentivize affordable housing.”

Tenant activists flooded the state Capitol in June as the rent debate escalated

For now, owners of rent-stabilized apartments in the city will have to look to the Rent Guidelines Board for the okay to raise rents. This year, the board approved a 1.5 percent increase on one-year leases and a 2.5 percent hike for two-year lease renewals. Wolf-Powers said the relationship between recent acquisition prices and the cash flows most of those properties generate has been off-kilter.

“Landlords were betting on being able to deregulate units and multiply [their] net operating income,” she said. “Now they have fewer options available to them for getting units out of stabilization and jacking up the rents, and they are stuck.”

The 10-year buildup

George Arzt, a veteran lobbyist who represents Gary Barnett’s Extell Development, said the industry was bracing for a “massive reform” after the sweeping November 2018 elections.

Nearly a decade after the Republican-aligned Independent Democratic Conference’s Senate coup, the Democrats regained control of the Assembly, and this time freshman legislators led the charge from the left — with support from the swelling ranks of the Democratic Socialists of America.

“These kinds of turns come only once in a generation,” Arzt said, noting that with the defeat of the IDC, Albany lost several moderate Democrats. “This is what they ran on, and this is what they got.”

State Sen. Julia Salazar, a member of the DSA, campaigned on universal rent control and joined the growing number of elected officials who vowed to reject donations from the real estate industry. Salazar recently told The Real Deal that she has no plans to stop pushing for radical changes to rent regulations but that she’s not opposed to open dialogue with the real estate industry.

State Sen. Julia Salazar, a member of the DSA, campaigned on universal rent control and joined the growing number of elected officials who vowed to reject donations from the real estate industry. Salazar recently told The Real Deal that she has no plans to stop pushing for radical changes to rent regulations but that she’s not opposed to open dialogue with the real estate industry.

Since November, the industry has sought out allies in the new Senate. And landlords, including A&E, Taconic and Cammeby’s, have started to engage in direct lobbying. While it’s standard practice for condominium developers to hire their own lobbyists, multifamily owners have historically relied on trade groups to represent their interests in Albany. The real estate industry poured more than $16 million into lobbying at the state level in 2018, for instance, mostly through large organizations like REBNY and RSA.

But in response to the urgency of this legislative session, individual landlords hired their own lobbyists in an effort to get a seat at the table.

Taconic’s Bendit said his company tapped lobbyist David Weinraub of Brown & Weinraub to arrange meetings in Albany and to gain direct access to elected officials.

“To the extent that there is legislation that affects our life and business, we’ll hire lobbyists to help us get our message across,” Bendit said.

Landlords are likely to be much more active in the Albany space than they have been historically, Weinraub said, in part because of the changes in the political landscape and the newfound power and influence of tenant activists. Asked if the real estate industry is prepared to fend off continued efforts to enact “good cause” eviction, which would have effectively limited rent increases for all rental apartments, Weinraub said the industry doesn’t have a choice.

“We better be. This is year one,” he said. “I don’t mean to suggest it’s a war, but these debates have really just begun in earnest with the new Democratic Senate.”

Weinraub said that the Senate’s move to the left and the resurgence of class politics have changed the way he lobbies lawmakers. The focus has shifted to narratives about the effect legislation will have on the working class and communicating those narratives to lawmakers in terms they understand.

Charles Bendit of Taconic

Investment Partners

“There are more tenants than landlords. That’s the political reality that legislators face. So you have to go from there,” he said. “That’s not to say [tenants] are going to win, but you have to deal with that political reality.”

Charting the unknown

The first week of June marked a sharp turning point in negotiations over the rent law, with dozens of protesters locking arms to block real estate lobbyists and others from whisking legislators off the Assembly floor. Within hours of the protests, 61 tenants were arrested and the Senate signaled that it had sufficient support for the Assembly’s package of bills.

A week later, the Senate and Assembly presented an amended version of that package as one bill.

Seated in the Dunkin’ Donuts inside the state Capitol building on June 12, CHIP’s executive director, Jay Martin, said Cuomo had “bullied himself into a corner” and was ultimately closed out of negotiations between the Senate and Assembly after repeatedly taunting the houses to move forward with the new legislation.

Martin — who previously worked as director of the IDC and chief of staff for Sen. David Carlucci — said CHIP was trying to get a meeting with the governor as soon as possible. (Martin is barred from lobbying the Senate for another 16 months, since state law requires a two-year hands-off period after leaving government work.)

“New Yorkers believe the governor was always the adult in the room,” he said. “But it’s clear he has acquiesced his leadership to the most vocal advocates in the houses.”

In the last week of the legislative session, negotiations accelerated and left Cuomo on the sidelines — surprising lobbyists, reporters and some of the governor’s largest campaign donors, who had been making predictions that the negotiations were headed for a “big ugly.”

Days before the bill passed, Douglas Durst, William Rudin and Richard LeFrak, who have collectively contributed at least $1 million to Cuomo’s campaigns over the years, called the governor and pleaded with him to intercede on their behalf, the New York Times reported. Cuomo told the developers to “call their legislators if they want to do something about it.”

The governor immediately signed the bill into law when it hit his desk. Now the real estate industry and regulatory agencies need to figure out how the new law will play out.

As multifamily landlords weigh the potential benefits of leaving the city behind, recent efforts to introduce tighter rent laws upstate in Kingston could complicate those plans. That city is considering opting into the Emergency Tenant Protection Act, which would allow areas outside NYC to adopt rent regulations if the vacancy rate is below 5 percent.

Martin said CHIP will first turn its attention to the Kingston area to fend off the ETPA push, along with other markets such as Rochester, Buffalo and parts of Nassau and Suffolk counties.

Martin said CHIP will first turn its attention to the Kingston area to fend off the ETPA push, along with other markets such as Rochester, Buffalo and parts of Nassau and Suffolk counties.

“No doubt that there will be more lobbying in those municipalities. We’re looking to ally with existing groups in suburban areas that advocate for fair housing,” he said. “We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel.”

Alex Panagiotopoulos, co-founder of the Kingston Tenants Union, said landlords targeting areas outside New York City are one of the driving forces behind the push for the new legislation.

“The day after the laws passed, we started talking about opting into the ETPA,” he said.

Political grays

It’s not yet clear whether the state’s housing regulator, the Division of Homes and Community Renewal — which has traditionally been underfunded and understaffed — is equipped to enforce the changes to the law.

While the agency’s Tenant Protection Unit received a $22 million bump in this year’s budget, HCR is now required to audit 25 percent of MCIs and will need to ensure landlords comply with the new caps on MCIs and IAIs.

There’s also some mystery surrounding how certain aspects of the bill will be applied. Landlords argue that new restrictions on condo and co-op conversions will completely stop such changes. Under the new law, eviction plans — which allow landlords to boot tenants if 51 percent of existing renters buy into their building — have been eliminated.

Instead, landlords would have to turn to noneviction plans, meaning tenants either leave on their own or when their leases are up. Under the new plans, 51 percent of the tenants would have to purchase their units before the landlord could move forward with a condo conversion. The previous law required only 15 percent under such plans.

Time Equities’ Francis Greenburger, whose company specializes in such conversions, said that while few landlords use eviction plans, he still finds the new threshold for nonevictions too high.

“The number of in-place tenants who are motivated to buy their apartments is far less than 51 percent,” Greenburger said. “By that time, the politicians who are putting this in will be somewhere else. This is a political sellout.”

Erica Buckley, a former head of the Real Estate Finance Bureau in the state attorney general’s office who now leads Nixon Peabody’s condo and co-op practice, said part of the new law grants certain waivers to the rules and is “unbelievably broad.”

Buckley said she could see a scenario where landlords negotiate to lower the 51 percent threshold if they can show that the purpose of the statute is preserved. She added that this is the first time in years that tenants have been given a more prominent seat at the table when it comes to planning the conversions of their buildings.

“The AG is going to need to look at conversions in a whole new way,” Buckley said. “Or the statute is going to look like a backdoor moratorium, which isn’t good for anybody.”

Meanwhile, RSA and CHIP are planning to bring their legal challenge against the state before July 15, several sources told TRD. The trade groups have tapped Andrew Pincus at the law firm Mayer Brown, who has been researching the law for 18 months, according to the sources.

The lawsuit will go beyond the new rent law and also focus on the broader significance of property rights, they say. The complaint will also likely hinge on a clause in the Fifth Amendment, which bars taking private property “for public use, without just compensation.”

Arzt, Extell’s lobbyist, said he stayed on the sidelines during the rent law negotiations but watched as a “very interested spectator.”

“No one is quite sure what the consequences of the bill are,” he said. “We’ll have to wait and see if it’s landlords crying wolf, or tenants saying that this is the best thing that ever happened.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified Laura Wolf-Powers as having the first name Anna. Anna is her middle name.