When Steve Kessner began buying East Harlem rental buildings in the 1980s, like most landlords of rent-stabilized apartments, he played the long game. Keeping maintenance and renovation costs to a minimum, Kessner made modest but steady returns on his 47 properties, many of them run-down and rat-infested, and one of which he bought for just $5.

When Steve Kessner began buying East Harlem rental buildings in the 1980s, like most landlords of rent-stabilized apartments, he played the long game. Keeping maintenance and renovation costs to a minimum, Kessner made modest but steady returns on his 47 properties, many of them run-down and rat-infested, and one of which he bought for just $5.

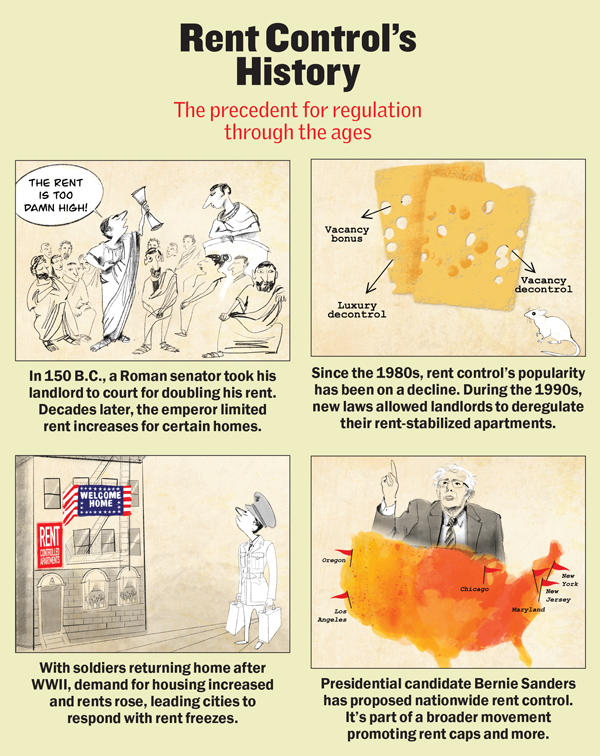

But when New York state lawmakers added ways to boost rents on stabilized housing in the 1990s and 2000s, it drew global pools of capital seeking higher returns. Three different buyers have since tried their hand at Kessner’s portfolio.

Hedge fund Dawnay Day bought the properties for $225 million in 2007, but the firm collapsed during the financial crisis. Next came Irving Langer’s E&M, notorious for evicting rent-stabilized tenants — a practice rewarded by a 1994 state law. Then Emerald Equity Group acquired the portfolio in 2016 for $357 million, financed with a $300 million acquisition loan from Canada-based Brookfield Asset Management, only to see state politics shift and the rent law swing back in favor of tenants this year.

Defeated in New York, big apartment building owners have been pouring money into politics to avoid a similar fate in California, Illinois and other states where rent control battles are raging.

National real estate investment trusts and global private equity giants have spent tens of millions of dollars lobbying in New York and California in the past year, according to an analysis of campaign finance records by The Real Deal.

The large institutional players are taking charge of efforts to fend off tenant gains as presidential candidates side with tenants and local landlord groups are bogged down by disagreements and disorganization.

Institutional investors control more rental housing nationwide than ever. Private equity firms and real estate investment trusts now own at least 200,000 multifamily rental units, according to an analysis of public financial filings.

Losing statehouse rent control fights can be costly. Just three months after New York’s sweeping reform in June severely limited increases of regulated rents for the foreseeable future, Emerald defaulted on loans for two buildings in its Dawnay Day portfolio. The firm, which had circulated a prospectus to investors in 2018 outlining plans to deregulate even more apartments and renovate a substantial portion of the Dawnay Day portfolio, began to miss payments in September.

Meridian broker Marvin Jeremias, who arranged the original financing, said that Brookfield was refinanced out of the investment long before the loans went into default. But Brookfield remains heavily invested in multifamily properties that politicians could rope into regulation, disrupting its plan to “redevelop well-located, older assets and earn an attractive return [for its investors] by raising rents.”

Meridian broker Marvin Jeremias, who arranged the original financing, said that Brookfield was refinanced out of the investment long before the loans went into default. But Brookfield remains heavily invested in multifamily properties that politicians could rope into regulation, disrupting its plan to “redevelop well-located, older assets and earn an attractive return [for its investors] by raising rents.”

Brookfield acknowledges that the strategy is at risk, noting in its latest SEC filing that “the imposition of rent control on our multifamily residential units could have a materially adverse effect on our results of operations.” The company, which manages assets worth $350 billion, declined to comment for this story.

The California lobbying rush

California’s largest real estate investors and trade groups, including the California Apartment Association (CAA), have pumped more than $110 million into lobbying in the state since 2008. Some $72 million of that was spent last year alone to preserve a statewide ban on new rent control measures, with almost 30 percent coming from just five institutional firms: Blackstone, Equity Residential, AvalonBay, Essex Property Trust and Invitation Homes.

On Equity Residential’s most recent earnings call, the firm, part of billionaire Sam Zell’s real estate empire, decried the “chilling effect” of rent regulation in New York City and told investors the new law had cost it $400,000 in application and late fees — roughly $40 for each of its nearly 10,000 rental apartments in the five boroughs.

But the revenue hit from fee caps pales in comparison to that from the new limits on increasing rent through renovations, vacancy and deregulation of units, which is now exceedingly difficult to do.

Equity Residential and Invitation Homes did not return requests for comment. Blackstone did not comment, and AvalonBay Vice President Jason Reilly said, “We do not publicly speculate on potential legislative matters.”

Jim Markel, a California regional manager at the commercial brokerage Marcus & Millichap, said Essex had “taken a leadership role” in last year’s fight against Proposition 10, a referendum that would have undone the state’s restrictions on rent control by local governments, and against a similar ballot measure now being pushed by tenant groups.

“Most of the major owners, as well as the private equity owners, are very up in arms about the prospect of rent control,” Markel said.

Michael Weinstein, president of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, one of the main groups seeking greater tenant protections in California, told TRD that before voters rejected Proposition 10, there were high-level negotiations between his organization and the CAA, which represents larger firms and institutional investors.

At a meeting convened by state Sen. Bob Hertzberg, it appeared a compromise had been reached. But according to Weinstein, it was rejected — not by CAA, but by two of the top institutional investors in California.

At a meeting convened by state Sen. Bob Hertzberg, it appeared a compromise had been reached. But according to Weinstein, it was rejected — not by CAA, but by two of the top institutional investors in California.

“The big interests said they wanted to go for broke,” Weinstein said. “We hammered out a deal, and then it was rejected by Blackstone and Essex, who were in the room.” (A source familiar with the meeting claimed that Blackstone was not present.)

“I think Blackstone cares so much about rent control because … like any public company, you have a commitment to your investors, to make certain you’re responsible and there’s an adequate return on your investment,” said Tom Bannon, the chief executive of CAA.

Essex CEO Michael Schall signaled on the firm’s most recent earnings call that the top firms have not let their guard down since defeating Proposition 10 and winning concessions on a rent control bill, AB 1482, that California passed this summer.

“We obviously track [rent control initiatives] pretty carefully and we kept our [campaign] entity, Californians for Responsible Housing, alive and well and organized in case of this,” Schall said about other rent control initiatives in the Golden State. “So we’ll wait and see what happens.”

Trade groups in disarray

Until recently, rent control was a local issue limited to city-based landlord and tenant groups battling in isolated jurisdictions. But in the past year it has been amplified with the help of Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Both have called for a cap on annual rent increases and for making it harder to evict tenants. The two politicians have ardent followings and immense media platforms, so their advocacy — along with an increasing number of rent-burdened tenants — could make rent control a lasting element of the nation’s political narrative.

Another factor that is motivating stepped-up political efforts by national investors in multifamily housing is the failure of New York landlord groups this spring in Albany.

The Real Estate Board of New York, Rent Stabilization Association and Community Housing Improvement Program spent $2.8 million on advertising to soften the blow of the state’s pending rent-law reform, to little effect.

The campaign, which sought to highlight mom-and-pop landlords, instead featured one who had poorly maintained her Upper West Side building, leaving tenants without cooking gas for 18 months. A ramen shop in her building, its gas burners rendered inoperable, had to close.

At least the trade associations collaborated on the ad buy. Since then, their efforts have been scattered.

Another industry group, the New York Capital Region Apartment Association, is organizing its roughly 400 members to sway lawmakers, but has rejected the idea of working with the other real estate lobbying organizations.

RSA and CHIP filed a federal lawsuit in July challenging the constitutionality of the rent law — a process that could bear fruit in three or four years. But the Real Estate Board of New York did not join the suit.

“We asked them whether they would be interested, and they declined,” said RSA’s longtime leader Joe Strasburg, who noted that REBNY “makes their own decisions, whether it’s right or wrong.”

A spokesperson for REBNY declined to comment.

Strasburg acknowledged that he did not even visit Albany during the legislative session, instead conducting meetings via phone. REBNY and RSA did meet with Democratic state Sen. Julia Salazar early in the year, but both parties said the meetings were not productive. No surprise there: The groups had for years supported Senate Republicans, who reliably defended landlords’ interests when the rent stabilization law came up for renewal every few years. When the GOP was swept out of power in the 2018 elections, landlords were left with little influence in the upper chamber.

Some REBNY members, including Brookfield and Blackstone, took their own lobbyists to Albany during the session. But REBNY, CHIP and RSA were not included in a March meeting between real estate interests and backers of a platform of nine state bills. Instead, Blackstone, A&E Real Estate Holdings and Taconic Investment Partners negotiated with the tenant advocates in the closed-door meeting, which was organized by Kathryn Wylde, president and CEO of the Partnership for New York City, a leading business group.

Although Blackstone is the largest owner of rent-regulated units in New York City, Wylde said she invited the global asset manager to the meeting as a potential source of capital for solutions to affordable housing and as a trusted expert on finance. “[Blackstone] just has some very smart people in residential finance,” Wylde told TRD.

The meeting was unusual, according to Wylde, but she said she expects to facilitate more gatherings about rent-stabilized housing in the future. Wylde said Blackstone, A&E and Taconic are “in it for the long haul.”

They are spending accordingly. Blackstone has put at least $595,000 into New York lobbying since 2015, while Brookfield has spent $2.2 million on state lobbying and given at least $619,000 to Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s re-election campaign in the same period.

Brookfield also lobbied against the changes to New York’s rent regulations — specifically, state Sen. Neil Breslin’s bill to allow municipalities outside of the city to opt in to rent stabilization.

Like other firms that have bet on multifamily housing, Brookfield may be looking to make such investments in upstate New York as an alternative to the five boroughs, given how regulations have tightened in the city, sources say. But Breslin’s bill, which passed, represents a threat.

According to Breslin, the Canadian asset manager came to his office to discuss the potential rent law but failed to win him over.

“Brookfield didn’t change my mind,” Breslin said. “I’m very proud of the legislation, and I’d do it again.”