Mark Nussbaum is a lawyer, deal facilitator, bridge lender and — The Real Deal found — the Chicago landlord of a sizeable portfolio, who shut down his law firm in January.

Two new lawsuits mentioning Nussbaum, together with a TRD analysis of Nussbaum’s dealings in New York and Chicago, shed some light on the varied business he ran.

To facilitate deals, Nussbaum would make short-term loans to investors so they could quickly buy and flip properties, according to sources and lawsuits.

He also allegedly diverted clients’ escrow funds instead of storing them, the lawsuits claim. (Nussbaum has denied the allegations in legal filings).

The lawyer’s troubles have reverberated through the real estate community and beyond. Some of his clients have been caught up in a commercial mortgage fraud probe by the Department of Justice and the Federal Housing and Finance Agency.

Nussbaum’s client list included Shaya Prager, Joel Schreiber, Moshe Silber and the late Mendel Steiner. In three New York City boroughs alone, Nussbaum’s firm or Nussbaum personally is tied to $71 million in loans backed by properties in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens, according to the TRD analysis.

Chicago deals

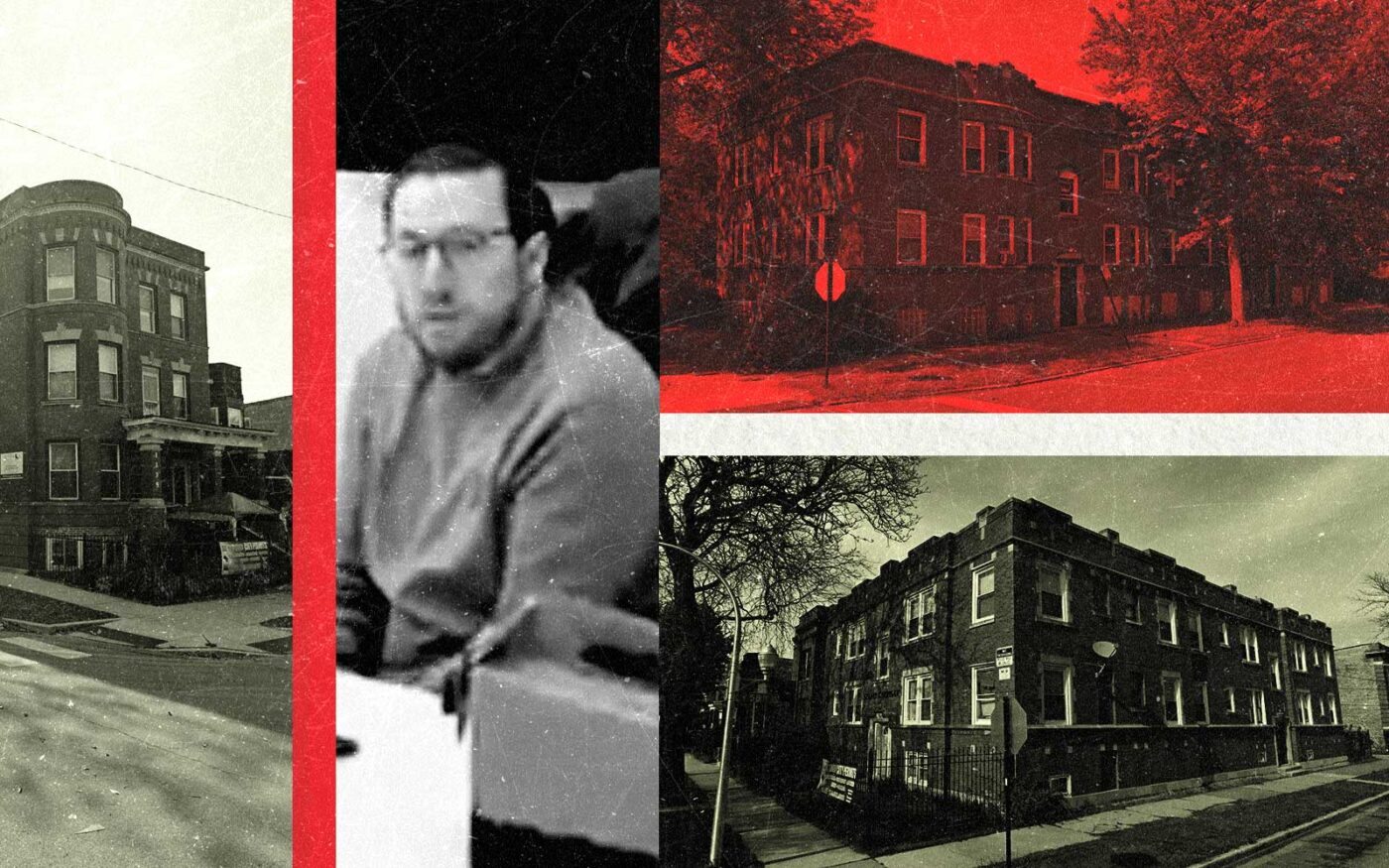

Nussbaum and his affiliated entities amassed a portfolio of at least 126 units of apartments on Chicago’s historically blighted South Side. The properties include rentals at 1135 West Garfield Boulevard, 1003 West 58th Street and 5757 South Morgan Street.

The buildings themselves — many low-slung, brick, built pre-World War II — are less notable than the way Nussbaum acquired them.

A familiar cast of investors from Lakewood, New Jersey, and New York owned some buildings before Nussbaum.

But Nussbaum signed guarantees on at least five loans backing these properties in Chicago, records show. Many then accumulated a litany of code violations spanning from risks of pest infestations to failure to maintain working furnaces and hot water.

A prudent investor might let the properties fall into disrepair or foreclosure, then buy them for pennies on the dollar. Yet Nussbaum played the role of the white knight, swooping in to save distressed property owners, often buying them for more than their previous sale prices. Nussbaum then worked to clean up code violations.

“For those properties in which he does hold some indirect interest, Mr. Nussbaum assumed control from prior, struggling owners and cured pre-existing violations,” Nussbaum’s attorney, Ethan Kobre of Schwartz Sladkus Reich Greenberg Atlas, said.

The story of West Garfield

Nussbaum entered the Chicago market in 2023, and since then, firms associated with him secured at least $18 million of mortgages tied to a dozen local properties.

Other investors may have preferred a high-rise on the Mag Mile or maybe something in the trendy West Loop, but Nussbaum favored the South Side in and near Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, an area with a poverty rate above 40 percent. Here, a key indicator for a strong multifamily market — population growth — was going in reverse: Chicago’s population grew 2 percent between 2010 and 2020, according to U.S. Census data, but Englewood’s dropped by more than 20 percent.

The properties in Nussbaum’s portfolio were bucking the trend. A closer examination of three properties shows their quick appreciation in price, along a similar pattern: Each went through a series of transactions, its purchase price increasing rapidly over a short period of time as it was bought and sold.

Nearly all the deals occurred between buyers and sellers from the Lakewood, New Jersey area or Brooklyn.

In a particularly extreme case, the sale price of the 9,000-square-foot rental building at 1135 West Garfield more than tripled in just a year.

Here’s how the transaction went: In March 2022, a Lakewood-based company called CMP Trading paid $245,000 for the building at 1135 West Garfield. A week later, CMP flipped the property to Myer Kahan of Lakewood for $420,000, a 71 percent increase. The same day Kahan scored a $315,000 loan — more than CMP Trading had laid down.

The property had code violations including a bathroom floor collapsing, fractures on the building’s exterior and cracks on the staircase.

A year after the flip, Nussbaum’s name started to appear on documents for 1135 West Garfield. Nussbaum’s MJNT1135 West Garfield LLC then took control of the property for $875,000 through a special warranty deed, and secured a loan from Roc Capital, a lender specializing in fix-and-flip loans, for $770,000.

The new sale price was more than double the property’s value a year earlier. Chicago records do not list any building permits, suggesting there were no substantial repairs or improvements.

Last summer, MJNT cleared the violations with the city, then secured a $1.1 million loan from Cliffco Mortgage Lenders, an amount 25 percent larger than the last sale price. This time, Eliazer Tauber signed for the loan to MJNT, instead of Nussbaum.

Cliffco did not return a request for comment.

Nussbaum’s other transactions in Chicago follow a similar pattern. Properties were purchased and sold and then acquired by Nussbaum, which obtained loans from either Cliffco, Teaneck, New Jersey-based Accolend or the Great Neck-based crowdfunding platform Sharestates. All properties show sudden increases in sales prices in an otherwise distressed market. Accolend also made loans to landlords from whom Nussbaum bought property or otherwise transacted.

When reached by phone, an Accolend representative claimed that unlike the rest of the U.S., real estate prices across Chicago have fallen in recent years. The rep declined to comment on the firm’s specific loans to Nussbaum-related entities showing the opposite trend — rising property values in Chicago. He only provided a first name, Boris, refusing to tell TRD his surname. (The company’s CEO is Boris Grinberg).

Some of Accolend’s loans were then sold to an affiliate of Athene Annuity and Life Company.

Nussbaum’s ties to the Windy City go deeper than a few deals. Illinois corporate records list 35 companies in which Nussbaum is a manager or agent. Almost all of the entities list their address as a suite in 1 East Erie Street, a six-story office in Chicago’s River North.

When TRD visited, the listed address was home to a visa and passport expediting service. A receptionist declined to answer any questions.

“Many of these LLCs were formed in contemplation of acquisitions that simply never materialized and reference properties in which Mr. Nussbaum thus holds no interest,” Kobre, Nussbaum’s attorney, said.

Flipped off

The Department of Justice and the overseer of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, are zeroing in on flips or sales between related parties.

Federal agencies have discovered a pervasive scheme where investors buy a property and quickly sell it to a straw buyer at a higher price. The inflated price allows the owners to obtain a bigger loan, often from Fannie or Freddie, than they otherwise would have received. The goal is to buy real estate with no money down.

Some conspirators, including Eli and Aron Puretz, Moshe Silber, Fred Schulman and Boruch Drillman, have pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit wire fraud. More indictments are expected to come. Many of the players at the center of the DOJ’s investigation have ties to Lakewood, New Jersey.

The DOJ has not brought any criminal charges or allegations of wrongdoing against Nussbaum. There is no known investigation into Nussbaum’s transactions in Chicago.

But the pattern of purchases raises questions about the rationale behind Nussbaum’s transactions. Why would Nussbaum, a real estate attorney, guarantee loans on struggling properties? Why then take control of properties to salvage them from code violations? And — most of all — why buy them at a premium?

The escrow business

Mark Nussbaum’s escrow business could have some answers. Money placed in escrow cannot be moved without the consent of a client.

A Brooklyn-based hard money lender sued Nussbaum this month, alleging he failed to return $5.5 million in escrow money. Another February lawsuit alleges Nussbaum paid a Borough Park investor hush funds with client escrow money. (Nussbaum’s lawyer said the allegations are fiction.)

But lawsuits against Nussbaum appear to show some tacit agreement between Nussbaum and his clients that money would go into Nussbaum’s escrow account and be used as short-term bridge loans. The allegations are as strange as they are serious about Nussbaum’s operation.

It is bizarre for an attorney to act as a bridge lender. But it’s equally as perplexing that in order to send the money to the end borrower it would have to go through Nussbaum’s escrow account at all.

Kelli Duncan contributed to this article.