Ignore the doom loops, depleted values and uncertain future: American real estate remains a respite for foreign investors to park their fortunes.

Beny Steinmetz, the Israeli diamond magnate, is already known to have put some of his wealth into buildings. His family owned a 60 percent stake in Manhattan’s Belnord, the luxury condo conversion project from HFZ Capital Group, the New York-based real estate development firm.

Now, recently uncovered documents show that a company linked to Steinmetz was also an investor in a Magnificent Mile office building in Chicago. It nabbed the stake as Steinmetz faced corruption investigations in multiple countries for bribing officials in Africa for mining rights in November 2017 and sought to protect his assets from creditors and adversaries.

The documents are from a trove of thousands of court records, corporate and real estate filings and dozens of source interviews collected over the course of an investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, an international consortium of journalists, including from The Real Deal. Taken together, they reveal how Steinmetz found himself under the eye of prosecutors and business rivals around the world and how he has held on since the mining scandal erupted.

Steinmetz teamed up with the company of a Greek businessman named Sabby Mionis and another investor to buy 500 North Michigan Avenue, a 24-story vanilla office building in Chicago’s high-end commercial district, the documents show. HFZ separately took possession of the property in 2019. Steinmetz was able to conceal his interest in U.S. real estate assets like this one through hard-to-trace shell companies, New York lawyers, and numerous agents while under scrutiny in the bribery investigations, underscoring the difficulty of efforts to improve oversight.

But this wasn’t just your typical foreign wealth finding its way to that most stable of assets — U.S. trophy properties.

Steinmetz’s firm, BSGR, had had its mining rights in Guinea revoked, and its former partner in the mining deal, Vale S.A., was pursuing claims against BSGR for lying about its alleged bribery to secure Vale’s investment. (Two years later, in 2019, the London Court of International Arbitration awarded Vale a $2 billion award against BSGR.)

There is no suggestion or evidence that Mionis — or his companies or directors — did anything illegal. Steinmetz and Mionis both say the deals were at arm’s length. Steinmetz sent OCCRP a response claiming neither he nor his companies had done anything illegal and contesting several of its conclusions.

As a typical investment, 500 North Michigan will not pay off. The building is 30 percent filled and currently offered in a distress sale. But Steinmetz’s involvement wasn’t the nail in the coffin: Chicago’s office market has been bleak since Covid. HFZ’s involvement did not help either. The firm has since collapsed, and HFZ founder Ziel Feldman alleges his former partner Nir Meir stole $30 million from a refinancing of the building.

Beny Steinmetz and Sabby Mionis

Beny Steinmetz’s family came from the diamond business, and Steinmetz expanded BSGR to Africa. He first set out to Angola amid a civil war and later ventured into Sierra Leone. Steinmetz developed relationships with De Beers and Tiffany & Co.

Steinmetz got entangled in scandals, including in Romania where a court found him guilty of conspiring with the grandson of the former king and of illegally obtaining land worth over $100 million.

Steinmetz’s biggest deal and his biggest problems were in Guinea. In 2012, Guinea’s new government started reviewing mining contracts. Investigators found that the widow of Guinea’s president, Mamadie Touré, had moved to Jacksonville, Florida, and used money from BSGR to buy real estate, according to court and property records reviewed by OCCRP.

In 2013, Steinmetz’s fixer in Guinea, Frédéric Cilins, traveled to meet Touré in Florida to stop investigators from obtaining the original copies of the contracts. But Touré was cooperating with a grand jury investigation, and she was wearing a wire. Cilins promised to pay her millions of dollars to hand over the contracts so he could destroy them.

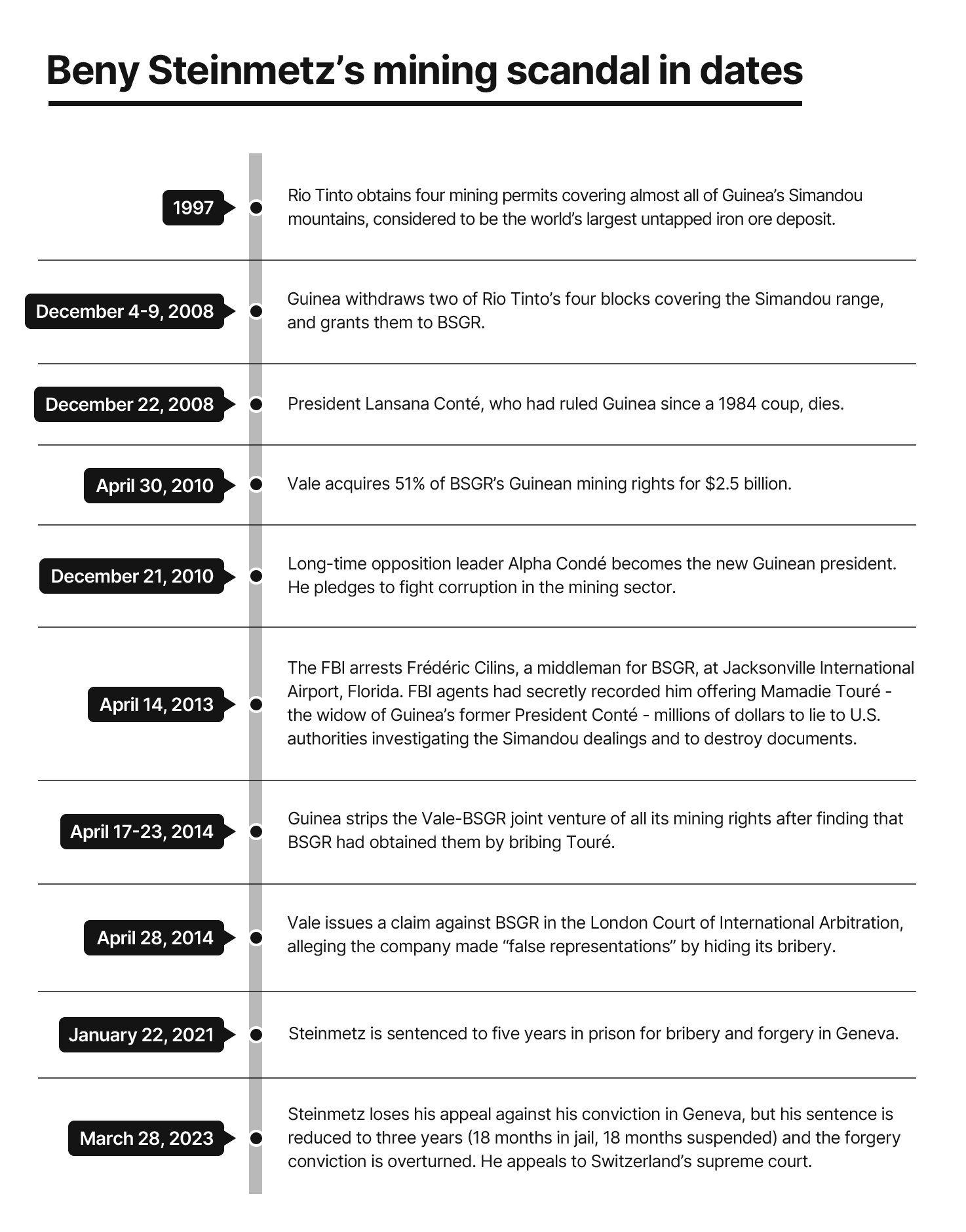

A Swiss criminal court in 2021 found Steinmetz guilty for bribing Touré in order to obtain the rights to lucrative iron ore deposits. He was sentenced to five years.

Steinmetz has denied charges of corruption and told the Swiss court, “I’m innocent and I have nothing to reproach myself with.” Steinmetz lost his first appeal, although his jail sentence was reduced from five to three years. He is now appealing the conviction to Switzerland’s supreme court.

Less has been reported until now about Steinmetz’s American real estate play. The opacity of his real estate investments made it difficult for any creditor — or reporter — to figure out where he invested his money.

OCCRP’s reporters eventually found at least five instances, including the Chicago office building, where firms controlled by businessman Mionis took actions that helped Steinmetz protect assets from creditors and allowed him to battle the corruption charges. Many of these deals were made through an obscure Bahamas-registered company called Global Special Opportunities Limited, or GSOL. Mionis’s lawyers said Mionis “did not help ‘shield’ Mr. Steinmetz, or ‘fight his battles’ at any point.”

In one example, an offshore firm owned by Mionis financed a $20 billion lawsuit brought by Beny Steinmetz’s mining company BSGR in New York against the billionaire George Soros. In another, a company owned by two GSOL directors sent millions of dollars to Steinmetz’s BSGR as it became entangled in a dispute with its business partner in a North Macedonian nickel refinery, according to OCCRP.

Steinmetz said through a lawyer to the OCCRP that he has “no control over GSOL and neither GSOL nor its affiliates are agents or nominees” of his.

Mionis described his relationship with Steinmetz as “a friendship, like I have with many business people,” in an interview with OCCRP.

Magnificent Mile

The purchase of 500 North Michigan included a large cast of characters and a complex set of company structures. Steinmetz’s people were active in putting the deal together, documents show. One of his partners claimed he had no involvement in the property.

But records reviewed by the OCCRP and TRD show that a Steinmetz-affiliated company had paid the $5 million towards the purchase price. They also show a Steinmetz-linked entity owned 11.5 percent of a firm called Perfectus Jerta JV LLC, which had a controlling stake in the property. That is according to records provided by a Mionis company named Fine Arts as part of a federal lawsuit and from the Swiss judgment against Steinmetz.

The ties between Perfectus Jerta and Steinmetz are evident in email exchanges and other records.

Perfectus lists Gregg Blackstock, head of mergers and acquisitions at Steinmetz’s BSGR and director of several other Steinmetz companies, as a manager.

In 2017, Blackstock emailed a lawyer in Steinmetz’s network about structuring the deal as part of Tarpley Belnord Corp, a Steinmetz-linked entity that had a stake in the Belnord, documents show.

That same month Blackstock sent an email to Kenneth Henderson of Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner asking to wire the $5 million down payment toward the property as a loan from Tarpley Belnord Corp.

Other names include the wealthy Tel Aviv-based Schapira family, which was set to be part owner but was later awarded an exit fee.

The family of Israeli real estate investor Amir Dayan came in to replace the Schapira family as an investor, records show. Blackstock said in an email that he and Dayan discussed forming a joint venture.

A lender, LoanCore, had talked with Blackstock about funding the building’s acquisition, But by October 2017, talks collapsed. LoanCore said it was uncomfortable with the structure of Tarpley Belnord, according to an email exchange.

“LoanCore hasn’t exactly behaved very nicely over the weekend,” Blackstock wrote in an email to Henderson.

Blackstock and Henderson shifted the structure. The buyers decided to close in an all-cash transaction. As part of the restructuring, Mionis’s Fine Arts agreed to come in at the last minute to invest in the property through a 1031 tax exchange, obtaining a 43.5 percent stake and ultimately ensuring the deal closed.

Documents reinforce the relationship that existed among the players.

“The people behind Fine Arts I know well and have a good history with,” said Blackstock in an email in court filings.

Perfectus Jerta JV, the entity tied to Steinmetz and the Dayan family, controlled the remainder of the property, outside Fine Arts’ stake, through a Delaware LLC called 500 NMA Acquisition.

As the details became final, Blackstock emailed Henderson. “Dayan’s sent two wires,” he wrote. “One of them for EUR 33M that somehow looks as though the bank sent in EUR and not USD. The other has been held back by HSBC compliance in Europe. He has asked, and I would tend to agree that we top this up and work it out later.”

Blackstock sent another email around the time the deal closed suggesting that Tarpley would be removed from the ownership structure.

“We’ll have to do a full reconciliation,” Blackstock said to Henderson. “Am discussing this with Amir Dayan next week.”

The deal closed on November 16, 2017.

In interviews with OCCRP, participants in the deal did not shed much light.

Mionis’s lawyers told OCCRP that 500 NMA Acquisition was owned entirely by Dayan and his family at the time of purchase.

Mionis said that Steinmetz appears to have “a joint venture with somebody else” in the property – an apparent reference to Dayan’s family — but did not elaborate further.

A lawyer for Amir Dayan said: “Mr. Dayan does not own the property nor does he have any connection to Beny Steinmetz.”

Henderson declined to comment to OCCRP. His law firm Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner said both Steinmetz and Tarpley had been clients, but did not provide further comment. Blackstock did not reply to questions sent by OCCRP.

The HFZ Connection

By 2019, high-flying New York condo developer HFZ Capital, led by Ziel Feldman and Nir Meir, eyed the Magnificent Mile property.

HFZ replaced Blackstock as a representative of 500 NMA Acquisition. HFZ was listed as a part owner and Meir’s name started showing up on documents in 2019.

TRD had already reported that Steinmetz was a known backer of HFZ’s projects, but the company denied it for years.

“He is not an investor in HFZ and he has no business relationship with HFZ,” a representative of HFZ told The Real Deal in 2016. (TRD eventually discovered an organization chart of The Belnord, showing that Beny Steinmetz’s family was the 60 percent owner of the property through Tarpley Belnord LLC).

HFZ, along with the Dayan family and the Mionis family, secured a $94 million refinancing loan from Granite Point Mortgage Trust for the Chicago property in 2019, loan documents show.

One Chicago commercial broker told TRD about being wary of getting involved in the financing at the time because of concerns about the ownership group.

In Granite Point’s loan documents, there was an unusual clause. It read: “in the event that Beny Steinmetz holds any direct or indirect interest in any borrower party or the property (including any profit interest), the same shall constitute a transfer which is not a permitted transfer.”

If Steinmetz held any stake, in other words, the borrowers would be in violation of the loan terms.

Before long, HFZ ran into financial challenges that had nothing to do with Steinmetz. It lost most of its properties, including the Belnord, to foreclosures. Feldman fired Meir in late 2020 and filed a lawsuit against Meir alleging he used the company as his personal piggy bank and forged Feldman’s signature on documents. In that lawsuit, Feldman claimed that Meir stole $30 million from the refinancing of the Chicago property. Meir had allegedly provided fake bank statements to HFZ showing that $30 million was held in the property’s account when the actual balance totaled just $813.

In February of this year, Meir was charged with orchestrating an $86 million fraud scheme by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg. Meir has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial while being held in Rikers Island.

The property at 500 North Michigan is now under contract to be sold, according to a source. With most of the property vacant, it is expected to be sold at a distress price for less than its debt.

Sam Lounsberry contributed reporting.