About 10 minutes into a three-hour City Council zoning committee hearing on Sterling Bay’s plan for Lincoln Yards, senior counsel Shelly Burke took to the microphone. What followed was not an overview of the $6 billion project, but an update on the firm’s efforts to boost diversity in its ranks.

Burke, the company’s newly-appointed director of community engagement and diversity compliance, described the developer’s new training and hiring programs she said would “create workforce opportunities for all of Chicago.” The only African-American executive out of 28 listed company leaders, Burke spoke as Sterling Bay principals Andy Gloor and Dean Marks, who are both white, sat at the front of the council chamber listening.

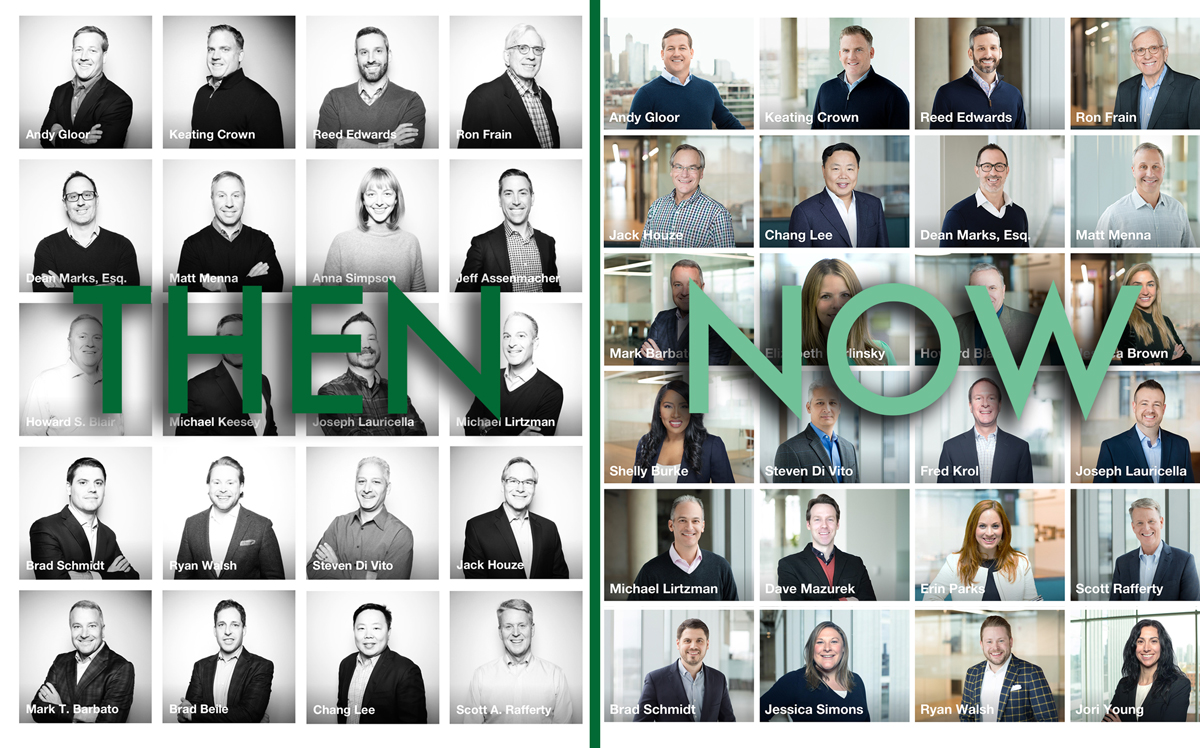

Afterward, Alderman David Moore (17th) questioned Gloor about the timing of Sterling Bay’s decision to add Burke and five other women to the company’s web page listing executives. He noted it happened only after three members of the Community Development Commission publicly mentioned that 19 of the 21 photos posted on the site’s “Senior Leadership” page were of white men.

Moore held up two poster boards showing the difference, prompting Gloor to defend the change.

“The reformatting doesn’t change that these people have all been part of Sterling Bay for a number of years,” Gloor said. “They are the most senior individuals with their particular expertise, and that has not changed.”

The tense exchange highlighted a persistent challenge the Sterling Bay has faced during the project’s punishing eight-month public approval process that began last summer: Demonstrating that a private real estate company, whose leaders mirror an overwhelmingly white and male-dominated industry, deserves to benefit from a $1.3 billion tax increment financing district bolstered by taxpayers in a diverse city.

The TIF district has not yet been approved by the City Council. But a zoning change for the project advanced through the committee last week, lining up Sterling Bay’s 54-acre master plan for final passage by the council Wednesday. The development is slated to build up to 6,000 apartments and 6 million square feet of commercial and hotel space.

Though one of the city’s largest developers, Sterling Bay is hardly the only real estate firm led predominantly by white men. The leadership pages for major developers in Chicago like Hines, CIM Group and McCaffery Interests are all filled mostly with white, male faces.

And in an industry composed mostly of privately-owned companies whose hiring practices lean hard on personal relationships, few companies are motivated to upset the status quo, said Megan Abraham, executive director of the Goldie Initiative, a nonprofit aimed at elevating women in commercial real estate.

“Until companies are publicly owned, the issue of diversity generally doesn’t emerge, because there’s just no mandate to change,” Abraham said. “The people making decisions are those in leadership, and when that’s a homogenous group of older white men, which is often the case, you’ll find no sense of urgency.”

Gloor told Moore during last week’s zoning committee meeting that hiring women- and minority-led contracting firms is “something we’ve consistently done in all our projects in Chicago.” It is also mandated under city code for any new development seeking financial backing from the city.

Sterling Bay has faced relentless public scrutiny over Lincoln Yards since last summer, including over how it hires contractors the development. Executives met with critical city officials like Moore, who ultimately voted to approve the zoning change last week.

Days before a Feb. 15 Community Development Commission hearing to approve the new tax increment financing request, Sterling Bay published a three-page “diversity and inclusion program statement.” The company has spent the past six months building and sharpening the company-wide plan, a spokesperson said.

The statement describes sponsorships in training and mentoring programs and lists members of an “advisory council for diversity and inclusion” who will consult the company on Lincoln Yards. Burke said the advisory council will help Sterling Bay “reach out to all parts of Chicago” to find contractors to work in Lincoln Yards, and will promote from within the firm to help it stand out in an industry “that has been dominated by white males.”

The firm also promoted Burke to the position of “director of community engagement and diversity compliance” after she personally asked Dean Marks to consider her for the position, she told the Community Development Commission last month. She was one of five women who had the word “director” added to their titles on the website since last month.

But in the fall, Sterling Bay lost a woman director in Erin Lavin Cabonargi, who stepped down as head of development to start her own development and consulting firms. Her position was filled by a man.

At the zoning committee meeting, Moore ended his questioning by telling Gloor and other Sterling Bay principals to expect the same scrutiny from the city in the future over its hiring practices. That will be especially true, he said, after the April 2 runoff election, when either Toni Preckwinkle or Lori Lightfoot will become the next mayor, marking a milestone for Chicago.

“I think we must continue to make sure we have racial diversity at all levels, not just in the project but at the company level as well,” Moore said. “Because let’s not forget, there’s going to be a new sheriff in town here soon, and that sheriff is going to be an African-American woman.”